- April 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Over at Florida Studio Theatre, Kimber Lee’s “brownsville song (b-side for tray)” breaks several dramatic rules, both structural and thematic. Lee starts her play at the end and ends at the beginning. She tells the tale of Tray Franklin (Wesley T. Jones), a promising young black man whose life was cut short by random gun violence. Talk about a story that’s been done to death …

But life, not death, is the point. Lee keeps her eye on life’s texture and particularity. That’s how she makes her play work.

She begins with words of fire. An incendiary monolog from Lena (Alice M Gatling), Tray’s grandmother. Instead of telling you who Tray was, she speaks of who he “was not.” Lena’s words of fire burn through you. But they’re directed at an unseen visitor. “This wasn’t just the same old story,” she cries. “He was mine.” I imagine the playwright withering in Lena’s apartment, digital recorder clutched in hand.

But the real-world playwright obviously didn’t back down. Because she tells Tray’s story. His narrative unfolds in non-linear fashion. His past is present tense. The beginnings of a happy story in an alternate universe.

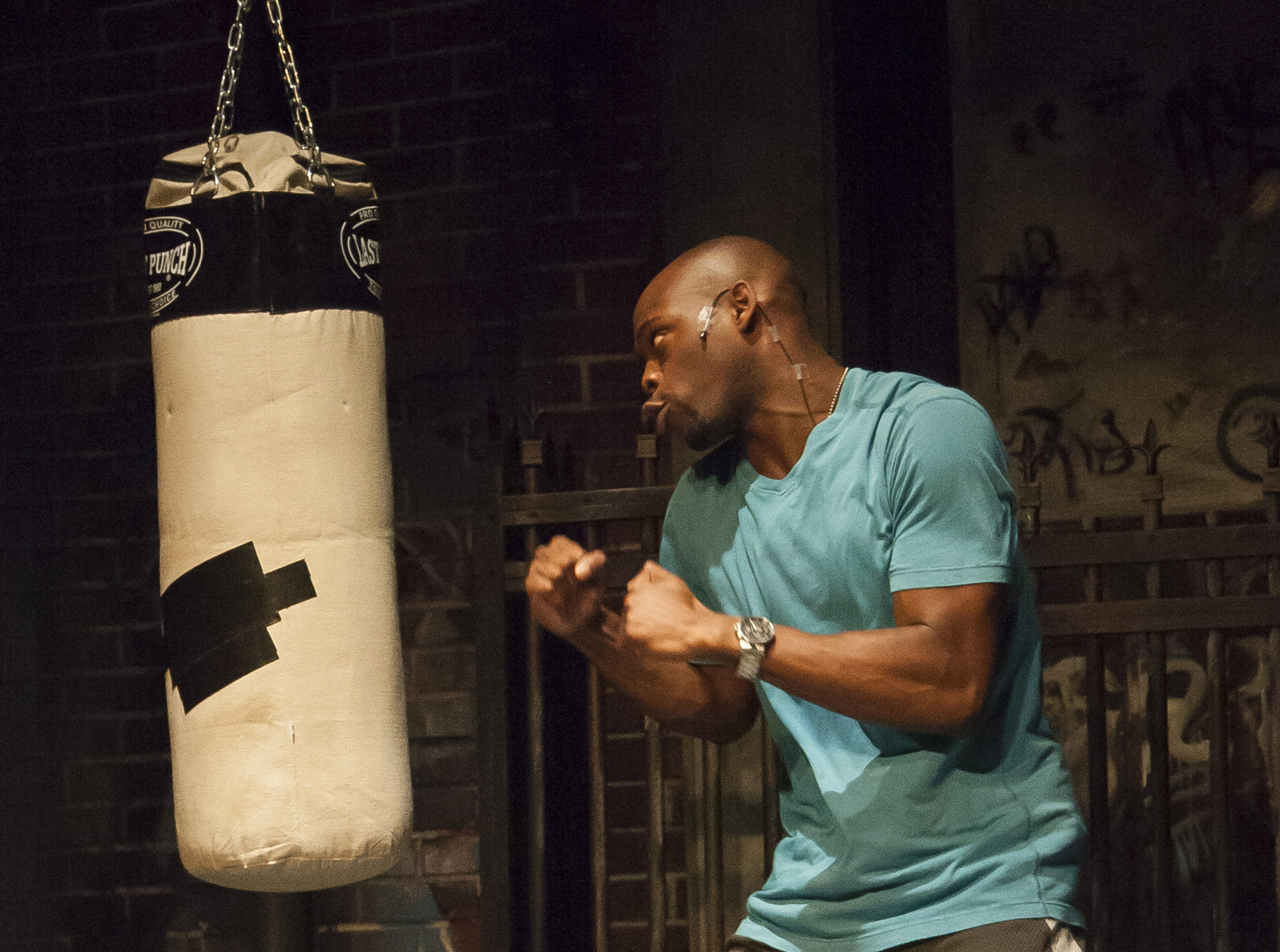

Tray’s an amateur Golden Gloves boxer. A devoted big brother to his little sister, Devine (Deysha Nelson). He works out relentlessly, studies way past midnight, brews coffee at Starbucks and hates his grandmother’s cooking. Now in his senior year in high school, Tray’s trying for a college scholarship and plans to be a teacher. With his eyes on that prize, he reluctantly allows Merrell (Rachel Lu), his estranged stepmother, to tutor him on his scholarship essay. But Tray makes it crystal clear that he has zero patience for Merrell’s “poor recovering alcoholic” story. And equally clear that “poor black boy from the violent ghetto” won’t be his story. He’s not so nice when he draws these lines. Tray’s a good kid, not a plaster saint. Yes, he does the right thing. But he also does what he wants—and resists Lena’s attempts to micromanage his life with eye-rolling exasperation.

Family, dedication, talent and heart. Tray’s got all of that going for him. Unfortunately, he lives in Brooklyn’s high crime Brownsville neighborhood. Or lived.

That bare summary doesn’t capture Lee’s ear for language and eye for character. Director Kate Alexander takes Robert Altman’s approach with Lee’s material. She makes you a fly on the wall, a voyeur of real events. Ken Goldstein’s set and Matthew Lefebvre’s costumes evoke Brownsville’s reality while avoiding the visual clichés of ghetto life. The actors bring that nuanced reality home.

Jones’ performance is a knock-out. In a clip show, I could show you the way he moves and reacts — the specificity he brings to Tray. Words alone don’t convey the honesty he brings to his characterization. He makes you sense the thought and emotions behind Tray’s eyes. On top of that, Jones’ boxing moves aren’t the typical thespic fraud.

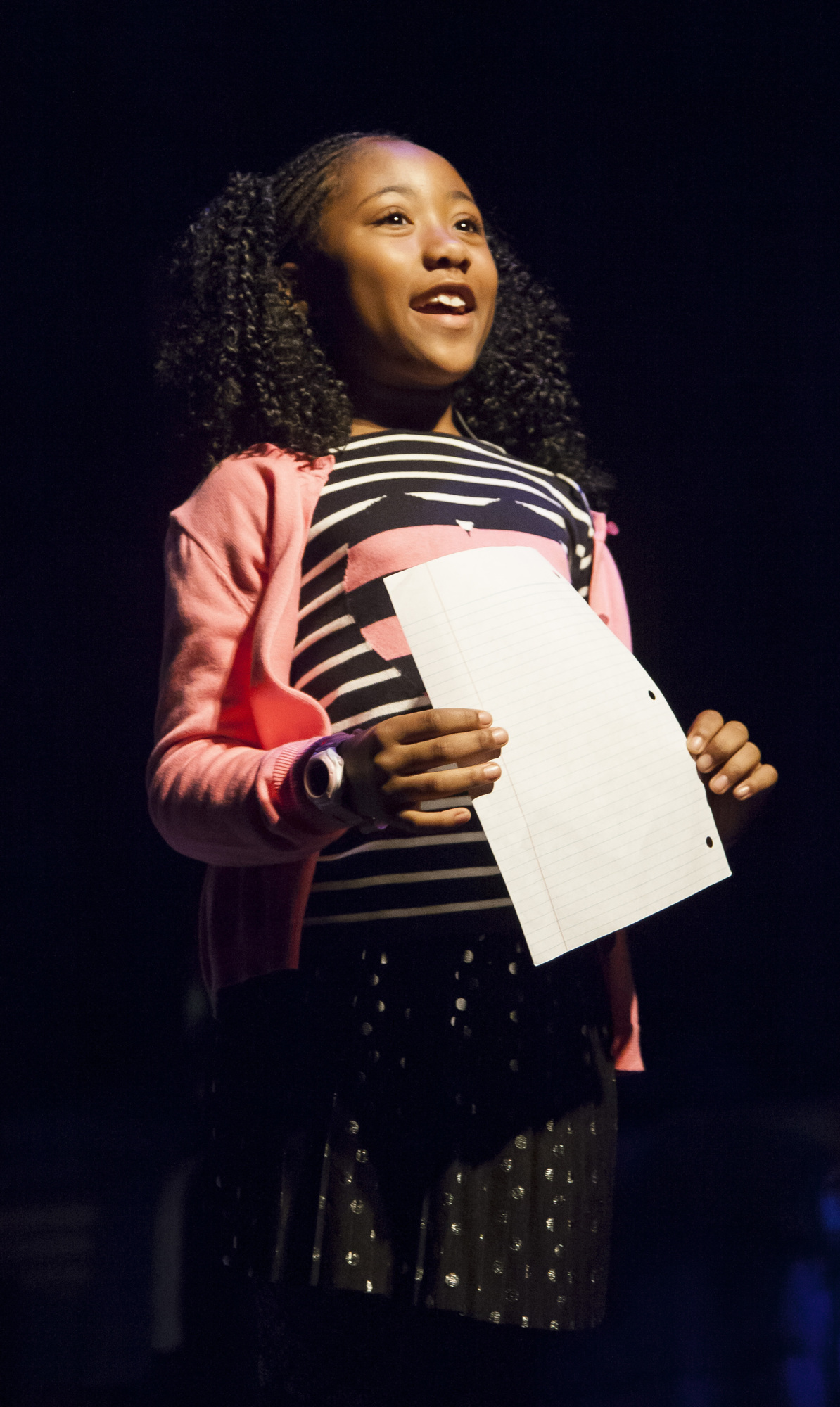

This high praise implies no faint praise for the rest. Gatling’s Lena has a heart too full to speak at times — and a raw determination that grief can’t kill. Lu’s Merrell vibrates with guilt, regret and shame. Nelson’s Divine is simply a cute kid, period. (She’s hilarious in the scene where she’s stuck with the role of a tree in an elementary school production of “Swan Lake.”) Warren Jackson is controlled and contained as Tray’s gangbanger friend, “Junior.” Tray refused to give his friend the silent treatment — and took four bullets in the chest as a result. Junior tells Lena the whole story. His tough façade briefly cracks. Tray didn’t deserve it, he says.

But nobody deserves it. As Lena points out.

Tray’s not a crime statistic. Nobody is.

Out of respect, the Tray Franklin of Lee’s play is a fictional character, not a journalistic echo of the real young man who died. The playwright makes this character live and breathe with defiant specificity. She ends her play with Tray’s scholarship essay. The hopeful words that should’ve begun his story.

“brownsville song” is a moving experience. It succeeds on its own terms — as characterization, not polemic. Lee never lectures you. There’s no big lesson at all, aside from “Thou shalt not kill.”

And it’s an old one.