- April 18, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

On Sept. 6, the City Commission voted unanimously to adopt a master plan for redeveloping more than 50 acres of public land along the bayfront. In a 3-2 vote, the commission also agreed to proceed with planners’ recommendation for the first phase of construction, a portion of which could be done as soon as 2020.

With their votes, the commission committed to an ambitious vision for transforming a bayfront that has been criticized as underutilized. The master plan calls for a new performance venue, dozens of acres of public open space, iconic bayfront architecture and more.

After the Sept. 6 meeting, city officials and representatives for the independent bayfront planning effort called the commission’s vote historic. It was the culmination of a five-year campaign to craft a community-backed plan for revitalizing the waterfront near the city’s center.

The ending of that effort marks the beginning of a new one. It’s one thing to dream up a future for the bayfront. It will be another to make it a reality. It will cost hundreds of millions of dollars to implement and require the forging of new public-private partnerships to manage the project.

So, after basking in the afterglow of the adoption of the master plan, all parties involved must address a towering question: Now what?

The entity responsible for overseeing the implementation of a multimillion-dollar master plan for redeveloping 53 acres of city-owned waterfront land does not yet exist.

If all goes according to plan, it will be forged within the next 100 days, a crucial transition period in the process of revamping the bayfront property surrounding the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall. Representatives for The Bay Sarasota — the group that produced the master plan — will coordinate with city staff on the creation of a new organization.

That group would shepherd the plan for building a sprawling public park into reality. Once that work is done, it would manage the public land in perpetuity.

It’s a new kind of proposition for the city, which not only runs all of its parks internally, but also oversees multiple business-oriented ventures on public property, such as the Van Wezel and Bobby Jones Golf Club.

But it’s one both The Bay and city staff are optimistic could be an optimal model for the long-awaited bayfront revitalization.

“We believe we’re presenting a transformational master plan and a proven way to make it a reality,” said A.G. Lafley, chairman of the Sarasota Bayfront Planning Organization.

In addition to presenting a master plan, The Bay recommended creating a new parks conservancy to govern the bayfront project. The city would first craft an agreement outlining the responsibility of the conservancy, as well as some details regarding how the independent nonprofit would operate and the city’s right to some oversight.

The parameters will be subject to commission approval, but in theory, the conservancy would be responsible for all things bayfront: procuring funding, producing more detailed design work, securing permits, selecting food and drink tenants, coordinating scheduling and more. And, once construction is complete, the conservancy would maintain the property, schedule events and handle other day-to-day roles.

This is a model that’s in place throughout the country, The Bay representatives said. From Central Park in New York City to Forest Park in St. Louis, local governments partner with private organizations that help fund and manage a prime public asset.

Just because the city cedes responsibility for governing the land, it doesn’t mean officials won’t have the ability to participate in the continued planning and development on the bayfront. Steve Cover, the city’s planning director, said each phase of the project would need to go through the city’s site plan review process. And, because the plans are for public land, staff will play a more active role in discussing the best strategy for implementing different elements on the property.

“The city retains the control. It’s their land.” — Bill Waddill

Long-term city planning documents will be updated to reflect the goal of building a public park on what is now primarily parking space. Cover said the city’s forthcoming transportation master plan will reflect the need to effectively bring people throughout region to a new destination site. City administration has already begun discussing financing options with The Bay, a conversation that would continue with the conservancy.

At the Sept. 6 meeting, commissioners told The Bay they expected any conservancy agreement to contain some provisions about the use of local workers in the design, construction and management of the site. They also asked for more details about how the city’s oversight would work in such a relationship.

“We’ll be very much involved with this,” Cover said.

The Bay Managing Director Bill Waddill said details like that will be a central part of discussions with city staff. No matter what happens, Waddill said, the city will have ultimate authority over the bayfront.

“The city retains the control,” Waddill said. “It’s their land. They’ll have the ability to terminate the agreement. Hopefully there will be incentives in there, if there are things we don’t agree on, to work it out.”

It is not yet clear who, exactly, will be on the conservancy’s board of directors. Waddill said some members of the Sarasota Bayfront Planning Organization intend to transition onto the new board. A community-wide search will likely take place to find new officials.

Regardless of who’s on the board, Waddill said the intent is to make the conservancy an organization that is highly responsive to public input. Members of The Bay believe their planning effort was so successful because they actively sought out community guidance. They think the same kind of transparency and accessibility will be necessary for a conservancy to succeed.

“Once we start building and activating the park, we’ll be asking other questions,” Waddill said. “How are we doing? What kind of events should we have? How was this event? What could make it better?”

Preliminary estimates place annual operating costs for the bayfront between $4 million and $6 million. Early funding models recommend a mix of philanthropic support, earned operational revenue and public funding to cover those expenses.

Once formed, the conservancy would focus on building the recommended first phase of the project, a pier and recreation area along Boulevard of the Arts. The Bay believes a segment of that phase can be open by 2020. The first test for the conservancy, then, would be following through on that target date — and ensuring the property is ready for a high volume of public use.

Waddill said the conservancy would strive to keep the community engaged in the redevelopment process over the course of 10 to 20 years, a challenge with which bayfront planners have already begun grappling. He believes it can be done as long as those responsible chart out a sure, steady path toward creating a new landmark within the city of Sarasota.

“We want to deliver on our promises as soon as we possibly can, but also be sure we don’t let anybody down along the way,” Waddill said.

To produce a master plan, The Bay raised a few million dollars from private donors.

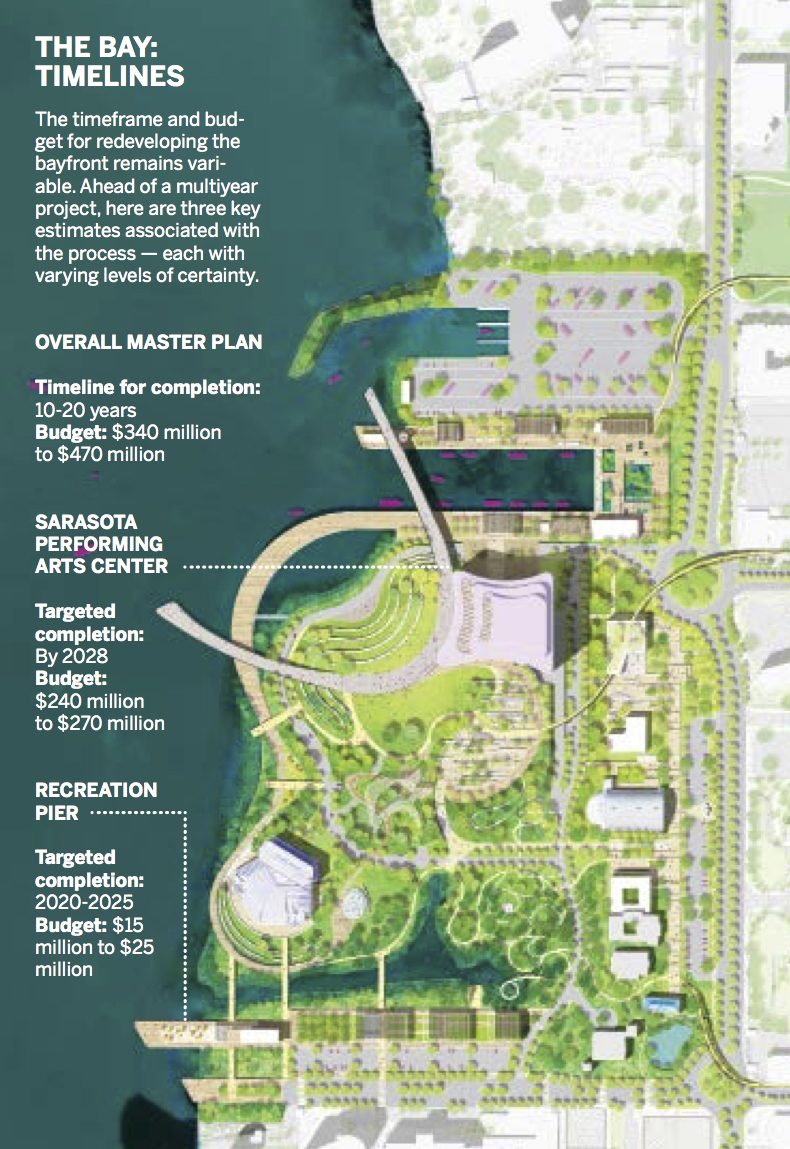

To build the master plan, it’s going to take somewhere between $340 million and $470 million.

Naturally, one of the most common questions Waddill hears relates to funding. He said The Bay was committed to creating a master plan that could actually be built, and the group is confident a diverse mix of funding sources will be available to pay for the project.

The effort will rely on a combination of public and private funding. Excluding the new performance venue, a project could take between $100 million and $200 million. At the high end, $100 million would go toward the park itself. Another $100 million would go toward infrastructure such as parking and boat facilities.

Although plans are subject to change, The Bay believes 40-50% of the total funding for that work will come from philanthropic sources. Paying for the rest will require local, state and federal public funds.

In its preliminary funding strategy, the biggest single public source The Bay recommends targeting is tax increment financing. The funding mechanism captures increases in property tax revenue within a designated area. Waddill said The Bay has talked to city and county officials about using property tax revenue from the area around the bayfront to invest into the project.

The Bay estimated as much as $60 million could be generated from TIF funds. Waddill suggested it was a logical fit, considering the redeveloped bayfront could be tied to an increase in nearby property values.

“If you’re in a condo, you’re looking at a 30-acre parking lot,” Waddill said. “When it’s done, you’ll be looking at a central park. It’s not hard to imagine your property will be worth more when you’re looking at a big giant park.”

Other major fundraising targets include $30 million to $60 million from a future city and county infrastructure surtax, $30 million to $60 million from state and federal sources and $10 million to $20 million from the tourist development tax.

The Van Wezel Foundation is working on a separate strategy to pay for a performing arts hall, which could cost between $240 million and $270 million.

Waddill acknowledged that $100 million to $200 million seems like a highly variable cost estimate, but he said certain elements of the project could go in different directions as more detailed designs and plans are produced. Similarly, projecting funding availability years down the line creates uncertainty.

Although the bayfront planners are confident the project can be built, key funding details remain to be determined.

“The further out you get, the fuzzier it is,” Waddill said.

By a wide margin, the most expensive single element of The Bay’s master plan is the construction of a new performing arts hall to replace the Van Wezel.

Representatives for the Van Wezel Foundation believe the cost — up to $270 million, per preliminary estimates — will be worth it. Supporters see an opportunity to improve the performance offerings, to strengthen the arts education programming and to create an iconic architectural centerpiece for a revitalized bayfront.

First, some details must be sorted out. City staff is working with the Van Wezel Foundation on an agreement outlining a governance model and funding strategy for a new venue.

The Van Wezel Foundation intends to transition the city-owned performance hall from a public to private operation. Although the venue would remain in public ownership, an independent board of directors would be responsible for management.

Jim Travers, a member of the foundation’s board of directors, said the governance model made sense for two primary reasons. One, it’s generally more successful for venues nationally. The new facility would more than double the size of the existing Van Wezel. Travers believes a private board, focused solely on the facility, could more effectively manage, program and promote the venue.

Two, it’s an effective tool for fundraising. Philanthropists are more likely to give to a private operator than to a government.

It’s unclear how much money will come from private donors, Travers said. The foundation has put together a fundraising committee, and the naming rights for the hall will be used as part of a fundraising strategy. The level of public involvement will be determined as negotiations with governmental entities begin in earnest.

Travers said ideally, groundbreaking could occur within five years, and the project could be complete in less than a decade.

The City Commission must approve any agreement, but City Manager Tom Barwin signaled city staff supported the governance concept.

“Hopefully the package will be smart, fair, reasonable and will really be attractive to donors,” Barwin said.

By 2020, The Bay Sarasota hopes a slice of the bayfront will become a hub for community activity.

The city has approved plans for the group’s recommended first phase of development for the bayfront site. The Bay targeted a “recreation pier” on the southern 10 acres of the property as the ideal first step for construction.

The area along Boulevard of the Arts would include two pier structures, open space that could be reconfigured for hosting events and recreational programs, a kayak launch, a mangrove inlet, a pedestrian bridge, parking space and food sales.

The Bay believes that will cost $15 million to $25 million to build by 2025. Planners think a segment of that area can be open within two years, though.

“Phase 1A” includes the open space, parking and food and beverage areas. The Bay sees an opportunity to host regular programming — and to experiment with what sorts of attractions are most effective for drawing people into the bayfront.

“We can build this small subset of the overall project, and we can test a bunch of different activation events,” Waddill said.

Phase 1A cost estimates range from $4 million to $8 million. The Bay recommended philanthropy

The construction of Phase 1, as planned, requires the demolition of the former GWIZ building at 1001 Boulevard of the Arts.

The fate of that building was the biggest point of contention at the Sept. 6 City Commission meeting. Preservationists argued in favor of saving the building and finding a new use, arguing The Bay Sarasota had not done enough to explore options other than demolition. The building dates back to 1976, originally built as the Selby Library.

Although two commissioners voted against proceeding with Phase 1, the majority of the board was comfortable with demolishing the structure. The Bay representatives said they could not identify a logical user for the property, given projected renovation costs and the building’s vulnerability to sea level rise.

But those who sought to preserve the GWIZ aren’t giving up yet. On Tuesday, the city’s Historic Preservation Board voted unanimously to recommend the city actively search for a tenant for the GWIZ building as the Phase 1 planning proceeds.

Critics of The Bay’s proposal for demolition say the group is now having a productive dialogue with preservationists about alternate options for the structure.

“It’s actually a nice little process that is going on,” said Christopher Wilson, chairman of the Sarasota Architectural Foundation board.