- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

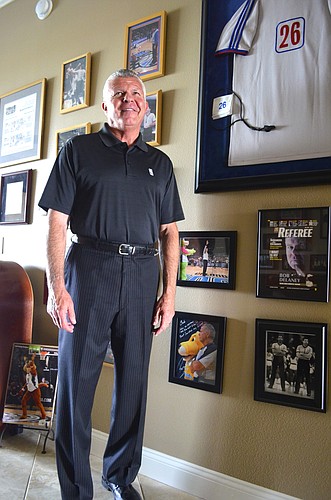

EAST COUNTY — The thumping and squeaking of sneakers trekking across the wooden floor of a basketball court is a comforting sound to Bob Delaney.

For more than 25 years, the court was his home.

“I felt this peace when I was on the basketball court,” Delaney said. “I knew the game, and it helped me clear my mind.”

The East County resident’s career as a referee for the National Basketball League helped pull him out of a severe emotional slump. Delaney suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder — feeling stressed or frightened even when no longer in danger, due to experiencing or witnessing a traumatic ordeal — following his work as an undercover agent for the New Jersey State Police.

Today, Delaney shares his story of how basketball helped him manage PTSD, or what he prefers to call operational stress, with military men and women and their families.

Delaney’s efforts, which have led him to just about every military post within the United States and Europe, have also landed him the 2014 Mannie Jackson Basketball Human Spirit Award.

He, along with fellow recipient Robert Johnson, will receive the award Aug. 7, at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, in Springfield, Mass. The award recognizes individuals considered as leaders in basketball who also play an active role in the betterment of their community.

Change of pace

The path to educating others on PTSD started with Delaney’s own experience.

After spending three years infiltrating the mob as an undercover agent for the New Jersey State Police in the mid-70s, Delaney’s family and friends noticed changes in his personality and physical appearance.

He remembers often feeling angry and paranoid — what he identifies today as “tell-tale signs of PTSD,” he said.

But, he didn’t lose his love for basketball. Delaney played the sport growing up and in college, but after years off the court and in law enforcement, he knew he didn’t have the athleticism to play on a professional level.

So, he became a referee, first for colleges. The NBA recruited him in 1987.

Calling the shots brought stability to his life, after living with a no-rules mindset.

“The court saved my life,” Delaney said. “It gave me my life back.”

The connection

Delaney started giving presentations to firemen and police officers in 1981 about his undercover experience and his work as a referee.

The stories of a red-faced Michael Jordan screaming within inches of Delaney’s face, and Shaquille O’Neal’s sense of humor are ones Delaney uses to connect with his audiences during PTSD-awareness presentations.

But, the presentations also were therapeutic for Delaney. Over time, they helped him cope with his feelings.

“When I would speak with law enforcement a little bit more of my personal feelings would come out — eventually I was telling more and more,” Delaney said. “They asked how I could meet with the mob guys, talk all kinds of things over dinner and commit crimes. Then, when I would get five miles down the road, I’d have to stop to throw up. I’d wake up in the middle of the night and my bed was soaking wet. But I learned that what is personal is universal. When I shared more of my feelings, other cops would come up to me and say they were going through the same thing.”

Although Delaney has never served in the military, he can relate to a soldier’s challenges. He knows the battle of returning to normalcy.

“I wasn’t on the same battlefield they were on, but I had a battlefield of my own,” Delaney said.

He remembers a presentation at Fort Sill, Okla.

He found ways to relate to his audience, swapping the term PTSD for operational stress and making connections between his experiences and the soldiers’, while also acknowledging the situations’ differences.

“I don’t pretend their boots are my boots,” Delaney said.

He also focused on his body language, making eye contact and maintaining a conversational tone to assure his audience he wasn’t being judgmental, he said.

After the meeting, a soldier approached Delaney to shake his hand.

He thought the soldier might have been holding a unit coin to give Delaney.

Giving a unit coin to someone is a sign of appreciation and is also a tradition, Delaney said. If the recipient doesn’t have the coin the next time the two meet, then that person is responsible for buying the other person a drink.

Instead, the soldier handed him a purple heart.

“I told him, ‘I can’t take this,’ and he said, ‘I have learned how to deal with the wounds you see, but today, you helped me deal with the wounds you can’t see,’” Delaney said.

Former winners

Previous Human Spirit Award winners include: Earvin “Magic” Johnson (2013); Grant Hill (2012), Chauncey Billups (2011), Samuel Dalembert (2010), Alonzo Mourning (2009) and Sonny Hill (2008).

Contact Amanda Sebastiano at [email protected].