- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

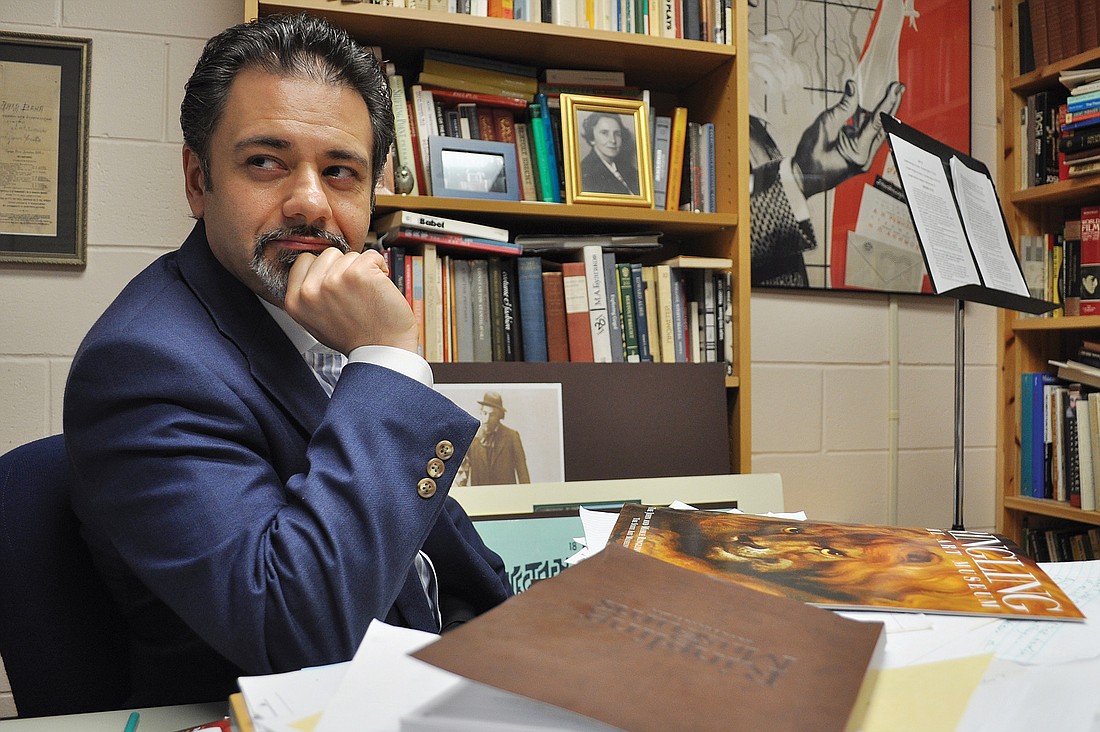

Andrei Malaev-Babel’s second-story office at the FSU/Asolo Conservatory for Actor Training is filled with so many books you fear grabbing one might cause the entire room to collapse.

There are books about how to perform plays, write plays, direct plays, analyze plays and, when you’ve got the time, watch plays.

There are books by Anton Chekhov, William Shakespeare and Virginia Woolf. There are plays by Edward Albee, Neil Simon and Bertolt Brecht.

Buried among the titles are Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s major works.

“I’m fascinated by him,” says the 44-year-old actor, director and teacher. “I consider him to be one of the most theatrical novelists, not because he’s flashy or in-your-face, but because he condenses the human experience … this kind of existence on the threshold of life and death, good and evil.”

Malaev-Babel has spent much of his career studying the Russian author.

He staged three major adaptations of the novelist’s work during his eight-year tenure with the Stanislavsky Theater Studio in Washington, D.C.

In 2000, he was nominated for a Helen Hayes Award for directing the company’s production of “The Idiot.”

“Dostoyevsky’s work is honest and sincere,” he says. “It doesn’t play the kind of games we have to play in everyday life for survival purposes.”

Next week he’ll direct the conservatory’s second-year students in an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s epic tome, “The Brothers Karamazov.”

Part murder mystery, part morality play, the story follows the complicated lives of three brothers as they struggle to make sense of their strained relationship with their deadbeat father.

Although the book was published more than 130 years ago, the subject matter continues to resonate with audiences today.

“The characters have survived the test of time,” says Malaev-Babel, who joined the conservatory faculty in 2006. “Every generation finds something relevant in it. It’s about incredibly passionate people who are put into incredibly difficult situations.”

Some directors would just as soon have a root canal rather than stage a Dostoyevsky adaptation.

Malaev-Babel, on the other hand, gobbles the stuff up — the human tragedies, the Oedipal themes, the existentialism and anguished debates over religion and free will.

As a result, he often has a hard time swallowing lighter plays and musicals. They seem shallow in comparison.

“In silly, fluffy plays, we laugh at shallow people,” Malaev-Babel says. “That’s fine. I admire the craftsmen of comedies. I’m more interested in the complex individuals who populate tragedies.”

It goes without saying that you’re not going to find a lot of beach reads in Malaev-Babel’s office.

A graduate of the Vakhtangov Theater Institute in his native Russia, Malaev-Babel has spent the past seven years traveling the world performing his one man-show, “Babel: How It Was Done in Odessa.”

The play is based on the short stories of his grandfather, Isaac Babel, a revered Russian writer who was executed in 1940 by order of Joseph Stalin.

The production is deeply personal for Malaev-Babel, who never got to meet his grandfather. Even though he’s performed the piece 70 times, he says he still finds something new in the material.

“Actors should constantly evolve and grow,” says Malaev-Babel. “One performance should be different from the next. It should breathe with nuances and subtleties because real life is spontaneous. Try to re-live your life exactly as it happened yesterday. It’s impossible.”

He says this is the key difference between watching a movie and watching live theater. Movies don’t change with each viewing. Live theater does.

He reaches for a copy of the book he just published on Russian actor and theater director Yevgeny Vakhtangov, who was a pupil of Konstantin Stanislavski, father of the first acting system.

“I don’t know about you,” Malaev-Babel says, “but I can never feel anything twice the same way.”

IF YOU GO

The FSU/Asolo Conservatory for Actor Training will perform “The Brothers Karamazov” from Nov. 1 to Nov. 20, at the Cook Theatre at the FSU Center for the Performing Arts. For tickets, call 351-8000.