- April 29, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

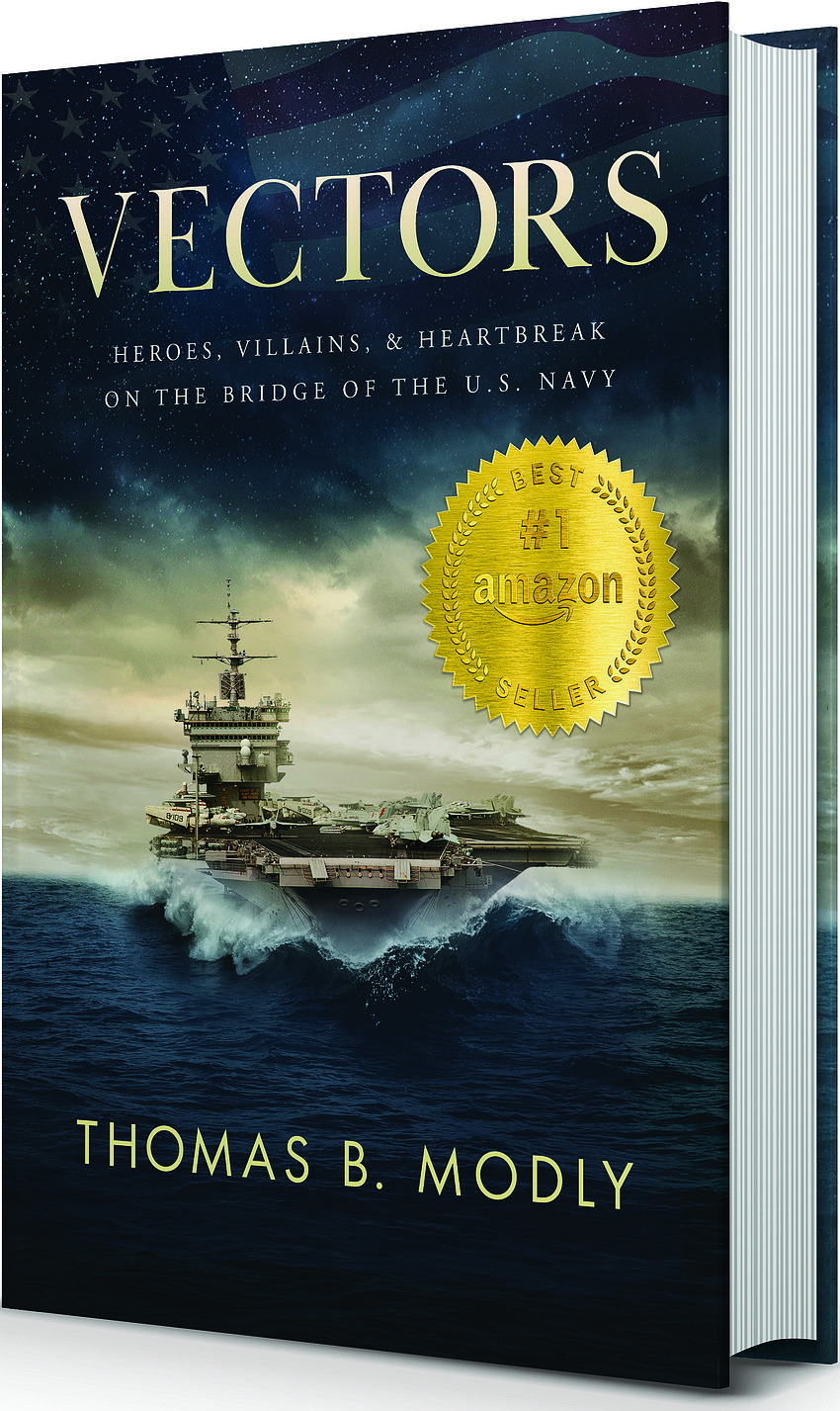

As a follow-up to the May 4 review in the Observer and on YourObserver.com of “Vectors,” a new best-selling Amazon book, Editor Matt Walsh interviews author Thomas B. Modly, former Acting Secretary of the Navy and now a Siesta Key resident.

Modly’s book chronicles his 19 tumultuous months in the Navy’s top job during the Trump administration.

And it was tumultuous indeed: mass shootings at two naval bases; the challenges of confronting seemingly insurmountable and dysfunctional bureaucracies inside the Navy and Pentagon; and the dealing with the ugly politics of Washington.

The climax of the book is what ultimately ended Modly’s term. After COVID began spreading rapidly across the 4,500-Sailor crew of the USS Teddy Roosevelt in April 2020, the captain of the ship went outside the Navy chain of command and sent an unclassified “signal flare” for help. The story went public and rocketed to the top of the national news cycles for days.

Modly ultimately concluded the captain’s breach of protocols and reckless email warranted the captain be relieved of duty. But that, in turn, created another media firestorm bigger than the spread of COVID on the carrier.

Modly ultimately decided the best way to end the controversy was to submit his resignation.

In the Q&A interview that follows, Modly shares details about the writing of the book and discusses some of the institutional politics of the Pentagon and Washington that stand in the way of innovation and a stronger national defense.

In the summer of 2020, after we had left the job, I started thinking about basically documenting what happened on the Teddy Roosevelt.

I wrote this long-form article that I was hoping to try to sell to the Atlantic or some magazine. It was called “The 25 questions I was never asked on the COVID crisis on the Teddy Roosevelt.”

It was about 25,000 words. I started talking to some people, a couple book publicists, and saying, “Can I publish this?”

And a couple of them said, “Well, you’re already at 25,000 words, and most books are 50,000 to 60,000 words, so why don’t you just write a whole memoir about everything leading up to that and give it more context?”

I basically took that essay and turned it into the final two chapters.

Then I decided I wanted to do something that talks about the “Vectors.” I was only in the job for 19 weeks, so I thought I could write a story about those 19 weeks with each chapter ending with the Vector.

The Vectors as they build over time give you a lot of insight into what I was thinking when the whole COVID thing started and the Teddy Roosevelt, too, particularly those last couple Vectors prior to my resignation, where I talked a lot about unpredictable circumstances and how this was the time for Sailors and Marines to really step up and not be afraid.

The irony was what was happening on the TR was exactly that — unpredictable circumstances and a time for Sailors and Marines to demonstrate courage and sense of duty.

I thought I needed a couple chapters up front to talk about who I was and how I ended up in the job.

The undersecretary stuff is very thematic. It talks about what was important to me and all the things I was trying to push, and introduces several of the characters. That’s basically 1 through 4. Those were optimistic times and I was hopeful that we were making a difference.

Chapter 5 is the start of the whole meltdown, when things really started to change, basically starting with (Defense Secretary Jim) Mattis leaving, (Admiral) Bill Moran’s resignation and Secretary Richard Spencer getting fired and with me becoming the acting.

So the next 19 chapters are set up to chronicle the next 19 weeks.

I was fortunate enough to get my calendar that had all my meetings on it, so I knew exactly what happened each week.

All from memory. The only thing that prompted me was my meeting schedule. Then I could piece it together. The actual details were just all from memory.

I got through Chapter 21, and I said, “Well, I’ve already written about those last two days and the last week and a half, those are the last two chapters.

I had written that 25,000-word article, so I tacked it on to the end, and then I realized that it was not part of the same book.

Those last two chapters, as originally written, were just a little bit more bitter and more defensive than I came to be after writing the rest of the book.

So I had to rewrite the last two chapters.

And then came the lessons learned. I had already written an op-ed about them, so I folded those in. And finally the Epilogue came to me literally about a week before the book was to go to press.

I had written an Epilogue, but I didn’t like it. So I just sat down one night and wrote a new one — the whole “Beat Army!” thing, which I really like.

I had the whole book outlined, week by week, and I thought to myself: “What’s basically the theme of this week?” Here’s what the Vector is about. Here is what happened that week.

Then I thought I really liked the idea of using some song lyrics to be the titles of the chapters.

So I literally sat down one night, like midnight, and went through my catalog of music and said, “I love this song. I love the lyrics in this. This totally fits.” And that’s how I came up with that.

It was after I outlined the book.

The lyrics were selected to fit the outline, and the title of the chapter was derived from the lyrics. They were in place before I wrote the chapter. I knew what the chapter was going to be about, because of the Vector and the events that had happened that week.

I told my kids: “I’m trying to appeal to a younger people with this book, and they said, “Yeah, Dad, these songs are like 30 years old.” True, but each one fits and means something to me.

I knew I wanted to use the book to highlight people who were unsung, people who do things behind the scenes and are never the ones you ever hear about too much, and I thought I didn’t want to talk negatively about specific people who are obstacles.

I thought about organizational behaviors and things that are really detrimental to the things that are important. They are the villains, and they can live in all of us.

The identities of the heroes and villains emerged after I wrote a chapter, because they are most relevant to that chapter’s story.

I wrote the first two chapters in the fall of 2020. That took me only a couple days to write. And then I had to put it down because we moved, and I was renovating my house.

I finished last April (2022), but it took me a year to get it published.

The last half to two-thirds of the book were written downtown at the Sarasota library. I would go down there in the morning, mid-morning, and I’d stay for two, three, four hours in one of those private little study cubes on the second floor.

I could generally crank out a chapter fully written, and then I thought about the next chapter, so that when I came back the next day or two days later, I could roll right into that next chapter because I knew exactly what I was going to say.

I did that 20 times, or something like that.

I’d say 90% came from memory.

The Ford met its timetable. She’s struggling a little bit. She’s on deployment now, and the ship itself is doing OK. But the entire class of ships is struggling to meet production schedules.

The JFK, which is the next one in line, whose christening I described and attended in December 2019, is another year behind schedule.

In that short amount of time, if you can get people to start thinking about those things and start recognizing those things as priorities, that’s significant progress.

That’s why I was so adamant about communicating every week with this entire organization, so they knew what I was thinking, what was important to me and what my priorities were. I was going to reinforce them in those messages.

I think we made significant progress in the first stages.

The interesting, and sad, part about that chapter for me was detailing all the things that took two to three years to put in place, and how within days they were completely unwound.

You can only try to make the most of the time you have, and hopefully, some of the things you do will stick and some of them won’t.

As far as reversing the ship namings (Note: the USS Agility and USS Republic names were scrapped), I found out in the media two days after they had made those decisions. The explanation for this reversal of a secretary’s sole legal authority has never been explained publicly, or to me. It just happened.

Never personally. He did write a press release announcing my resignation in which he wrote something like “We thank Tom for his service.” Nothing personally. I have not spoken to him since April 2020.

The Army versus Navy thing is probably more subtle than overt. I sensed he didn’t trust the strategic assumptions of the Navy and didn’t trust the admirals.

The bigger intrigue — more than my role as Navy secretary and Naval Academy graduate — was the fact that Robert O’Brien, who was national security adviser to the president, was a big-time, self-proclaimed pro-navalist. He really wanted to push for the growth of the Navy. He was a big fan of the work I was doing and my push to grow the Navy. He was emerging as a rival of Esper in a big way.

Esper knew the president wanted a bigger Navy, but he wasn’t willing to figure out where we could get the money to do it. He wasn’t willing to take it from anyone else, specifically the Army. In my opinion, that was really the only place you could get it.

That’s part of what the game is — learning how to build relationships so you can accomplish something. You don’t have time. That’s the problem.

We picked the new Chief of Naval Operations, Michael Gilday, in the summer of 2019. He has had six bosses since then.

You can’t have that lack of continuity at the top of a big organization like that if you really expect to put in some big rudder movements to change it.

I personally think they should consider cutting down the number of political appointments in the Defense Department to like 100 to 150. They have more than 300 now. That is too many.

It would be better to have the service secretaries themselves have 10-year appointments like the FBI director.

It was kind of the pervasive attitude across the service.

It really came to fruition with Teddy Roosevelt, I was begging the CNO. “This is your Navy. These are your ships. You need to go out to Guam. You need to call this captain.”

His response was: “That’s not how we do things in the Navy. We trust the chain of command.”

My response was: “Well, the chain of command doesn’t seem to be serving you too well right now. I think those days are over. You’ve got to get involved.”

There are a couple things at play here. There is a long-term Navy cultural thing.

Back in the day, you essentially gave these captains the keys to their vessels and said, “Ok, we’ll see you nine months later. And you’re on your own.”

So there’s a little bit of that. There’s an inherent trust in the chain of the command. Largely you had to do it that way because there were no communications like we have today.

But, as I wrote in the book, it’s not 1895 anymore. Information travels quickly. And you can have a situation like that where a captain uses bad judgment, and then all of a sudden it becomes public and political. And that reflects very poorly on the Navy and that causes problems in Congress, and Congress is our customer, and you want to try to avoid that.

The other part is that there is a fascination with optics — the desire to manage the optics and not necessarily make the best decision at the time. Rather, there is a bias to make the best decision for the optics. That drives a lot of decision making.

The third part is this whole legal concept of undue command influence. You’re talking about a potential legal proceeding where if a senior naval officer may get inappropriately involved in something that may end up in a court martial, that can be sort of a valid defense of someone who is accused of something.

This causes senior offices to be overly cautious about getting involved directly and allow the “process” to run its course without engagement. I believe it has created a culture where the top people are frightened. They’re frightened about doing anything. So they stay away from controversy and controversial decisions.

And they rarely make decisions where it comes down to: “I disagree so strongly that I’m going to throw my stars on the table and resign.” That never happens anymore. Never.

I’m more worried about internally than I am externally.

I don’t see how these political divisions and positions we are seeing now are reconcilable. They appear fundamentally, and diametrically, opposed. In the book I talk about “divided national memories” as one of the biggest villains we face. That villain must be confronted and defeated. We must come to a broad, national understanding about what has been, and is, good about the country to improve it and properly defend it.

Editor's note: This article has been updated with added context.