- April 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

This year the city of Sarasota plans to wrap up a long process of replacing existing zoning and related codes with a new form-based code system.

Sarasota’s current system — traditional zoning — has shaped the city to date by dictating what uses are appropriate in a given area or property and setting rule-based standards like setback requirements, parking ratios, square footage or height limitations, number of units, etc., but allowing for diverse design.

Traditional zoning results in distinct commercial districts and residential districts, with mixing coming on a broad level, like residential areas with commercial only at major intersections or along major boulevards. It allows for a mixture of diverse building styles alongside one another, from housing styles on a typical neighborhood street to the differing styles of high-rise condo complexes along the bayfront. We see all of this in Sarasota today.

In contrast, form-based codes dictate building and open-space design criteria for mixed-use patterns akin to downtowns of older, more traditional cities. They strive for more urbanist downtowns (think Manhattan and European cities — dense, with little or no setbacks) where commercial locations interact with residential and open spaces.

They emphasize coherent and consistent neighborhood look and feel, including buildings’ scale and relationship with open spaces (the outside of the building) over micromanagement of a building’s internal configuration (the inside of the building). Think Celebration near Orlando to picture one example of form-based codes in action.

With a form-based code, one neighborhood might designate a look and feel of Florida Cracker architecture with its metal roofs, large porches or balconies and wooden railings, while another might prescribe the Bauhaus-inspired Sarasota School of Architecture style with big windows and wide sun shades.

The outskirts might emphasize single-family homes with interspersed clusters of commercial spaces, and boulevards with grassy medians, while downtown mingles apartments, condos and commercial spaces with narrower streets and wider sidewalks. In many ways, The VUE would conform with many form-based codes with its mixed-use, urbanist street placement and consistent high-rise look.

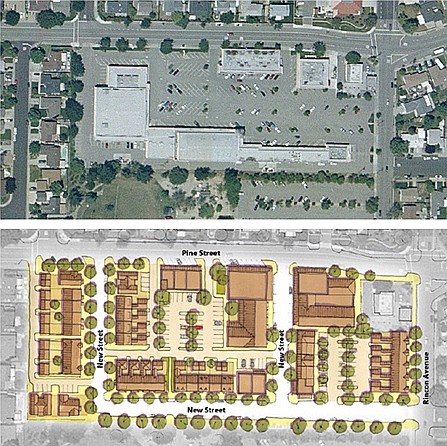

The picture included here provides a typical example of a contrast between a “traditional” project and a form-based project. Now the traditional example, a photograph, is less lovely than the appealing sketch below it, but looking past that, these two show the contrast.

The traditional zoning separates commercial from residential. In contrast, the form-based example has far more residential space in it than commercial — a clear shift in the balance of use — with far fewer parking spaces. It is unclear how the people going to the commercial establishments will get there. And don’t say transit — no amount of improving transit service or changing development patterns has increased transit use in any city in America.

Form-based codes come with trade offs. At their best, they regulate design approaches to simplify land use entitlement for clearer expectations for developers and planners. Emphasizing design loosens traditional zoning requirements to streamline the development and building approval process. The goal is for developers to get by-right development approvals and streamlined entitlement approvals as long as they conform with design principles that are publicly discussed and codified by the City Commission. Builders go along on design, and in return they have more freedom to choose densities and unit numbers and more certain and timely project approval.

But a problem occurs if form-based codes replace traditional zoning’s relatively objective requirements for project approval with more subjective ones. Overly prescriptive subjective criteria around look-and-feel replacing more objective conventional criteria such as use and size can hinder trying new looks. That allows for less creativity and innovation, and can make for a more cohesive but less interesting city.

Another problem is, while generally successful at providing more mixed use and diversity of neighborhoods and integrated public spaces, form-based codes often hinder planning participation by the public. The process for setting the design principles of a form-based code empowers a small number of community activists and stakeholders to have great influence over the criteria established.

Face it, only a few of mostly the same folks participate in these kinds of meetings. The vast majority of people who want to build, buy, remodel, upgrade or move within the city will have not had any say in the criteria that will determine what they can and cannot do on their own property.

Also, form-based codes are often much more difficult to enforce than traditional zoning. For example, what typifies a certain design, for example, Cape Cod or Mediterranean, differs by individual. For this reason, it’s also more prone to litigation than traditional zoning. This may be why less than 1% of cities in the United States have put form-based codes into place, most of them in the Southeast and California.

But the worst disaster comes when both traditional zoning and form-based code approaches are used to their fullest extent. That means each new group of political leaders, stakeholders or activists can intervene and micromanage criteria for both design and use, both outside and inside every new construction.

Instead of sticking to agreed-upon principles, compliance would micromanage nearly every aspect, requiring lengthy public reviews and approval processes for both design and use that would change with public opinion. The fact is, allowing for continual public input on every single major construction reinvents the permit wheel for every project. This is the kiss of death for affordable city development. Developers find themselves facing traditional restrictions AND design restrictions, and gain nothing in return.

All this can create substantial incentives for developers to move projects to other jurisdictions or vastly increase costs to home and business buyers and other consumers. When the cost of development goes up, such as for delays, the cost to consumers goes up, because that cost has to be paid from somewhere.

Some of the big controversies going on right now over pending development projects hinge on the public micromanaging of nearly every aspect of construction. People who are upset about The VUE point to disagreement on the setback or on the density of the project — traditional zoning criteria — and exterior design as well. Organizations such as STOP! have fought for a public say in every major construction project, demanding traditional zoning process public review and comment on all significant projects even if they are fully conforming. Form-based codes would not support either group.

So should Sarasota use form-based codes?

They are not necessarily a bad idea, but they are tricky and not a panacea. Their best use is to supplement modified traditional zoning, using agreed-upon design principles as much as possible, but limiting the scope for subjective criteria and retaining objective measures as much as possible.

Sometimes setbacks and parking requirements are really important. Indeed, the founder of form-based codes, Miami architect Andres Duany, created them originally as voluntary criteria for developers who wanted to create big projects with better mixed use and design than traditional approaches provide.

Following up on that approach by adding design criteria while alleviating some traditional zoning restrictions and having a clear and speedy process for approving projects could give Sarasota a basis for better integrating new and older downtown development and public spaces into a better functioning whole.

Adrian Moore is vice president of Reason Foundation and lives in Sarasota.