- March 13, 2026

-

-

Loading

Loading

Although the sparkling waters of the Gulf can portray calm and serenity, its current can pull an unsuspecting swimmer out to sea and into danger.

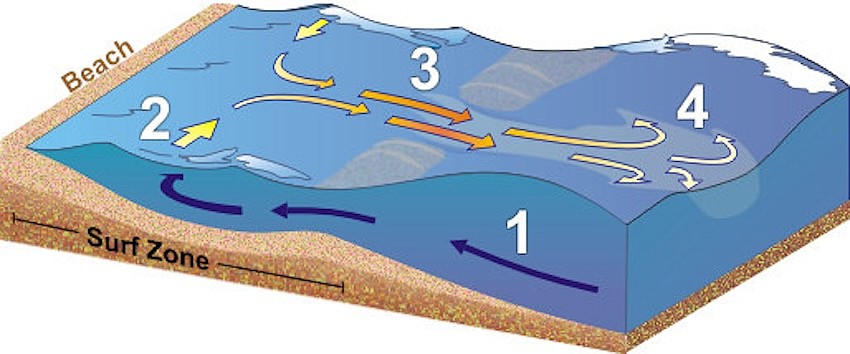

Rip currents are formed when water from breaking waves finds the path of least resistance to return to the sea. When that rush of water out to sea is concentrated in one place and strong enough, it forms a current that can pull even the strongest swimmer far out to sea.

The natural phenomenon is potentially deadly.

On Labor Day, a 20-year-old drowned after he and another swimmer on Bean Point Beach on Anna Maria Island were pulled out to sea from a rip current. A Longboat Key Police Department boat unit recovered the body of Abhigyan Patel the next day after an exhaustive multi-agency search. In 2024, a rip current pulled seven people out to sea off Lido Beach. Mariano Martinez rescued all seven of the swimmers, earning him the National Medal of Valor by United States Lifesaving Association.

Rip currents are the leading cause of water rescues. According to a report by the United States Lifesaving Association, rip currents cause 78% of water rescues on the Gulf Coast.

Manatee County lifeguard Cliff Talbott said rip currents and underlying medical emergencies are the most common things that lead to a lifeguard jumping off his stand and into the Gulf. Manatee County Beach Patrol Captain Marshall Greene said of the 300 rescues performed by the agency so far this year, he estimates at least 60% to 70% were due to rip currents.

On beaches with lifeguard stands, flags signify the level of safety. Green means there is a low hazard, yellow means moderate and red means there is a high risk of currents. Two red flags signify the water is closed to the public, and purple means dangerous marine life has been spotted.

On beaches without lifeguard stands, like on Longboat Key, knowing when rip currents are prevalent is an important thing for beachgoers to monitor.

The National Weather Service publishes surf zone forecasts early each morning, which give three levels of risk: low, medium and high.

Longboat Key Town Manager Howard Tipton said the town places signs and posts on social media warning of rip current risks when surf conditions are not ideal, but that beaches on Longboat Key are swim at your own risk. He said those who are not confident in their swimming ability should exercise caution.

“People’s ideas of the Gulf is of this tranquil lake, and it is sometimes, but sometimes it’s not and waves and currents can get rough,” Tipton said. “So it’s important to be safe.”

Rip currents don’t discriminate and are possible anywhere waves splash ashore.

“We get rip currents all up and down our beach every day,” said Greene.

They can sometimes be seen if you know what to look for. Evidence of a rip current can include a break between waves, a difference in water color, or a line of foam or seaweed moving out to sea.

“Rip currents can be visualized by like a cloudiness in the water that is moving out toward the open ocean,” said Greene.

There are, however, certain features that can make rip currents more common.

They are more common near piers, jetties and groins, where they can occur even during a low-risk surf zone day.

Some clues include:

Source: NOAA

According to a statement from Sarasota County Fire Department Lifeguard Operations, although all local beaches are susceptible to rip currents, some geographic features can lead to a higher risk, or a false sense of security.

“Beaches like the North Jetty Park are extremely susceptible to a major rip current along the jetty when winds and currents are coming from the north. Beaches like Lido and Siesta have a shallower entry and it can give swimmers a false sense of security, thinking that the shallow water is safe and they go further out which can put them right in the mouth or feeder of the rip currents,” the statement reads. “Beaches like Nokomis, Venice and Manasota have a quick drop off which, when strong currents or waves are in effect, can become hazardous because the water gets deeper much more quickly.”

Rip currents can range in speed from 1 foot per second (less than a mile per hour) to 8 feet per second (5 miles per hour) in the most dramatic instances. Greene compared the strength to that of a lazy river at a waterpark.

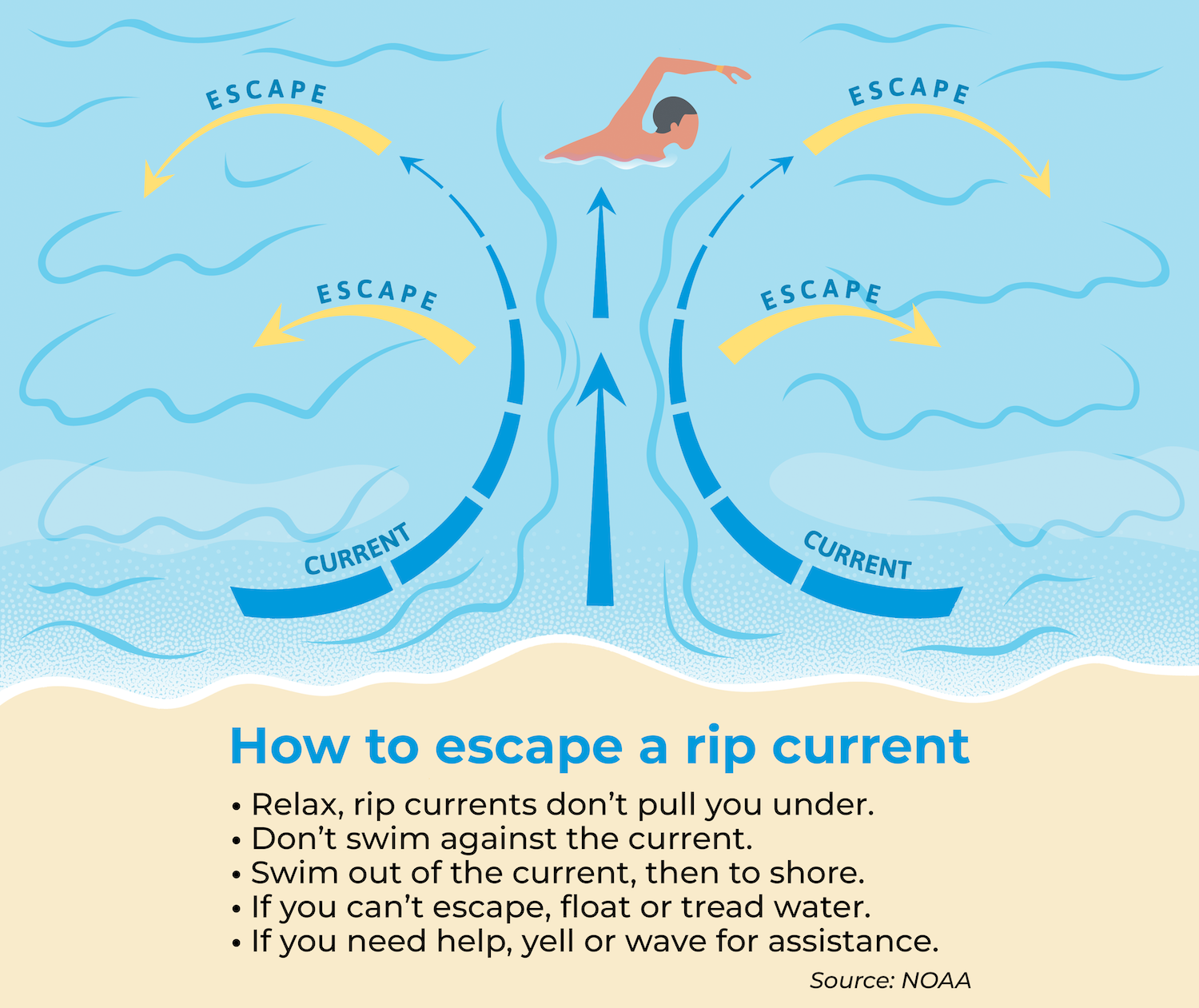

Rip currents don’t pull swimmers underwater, according to USLA and NWS.

Greene stressed that those caught in a current should not try to swim against the current, but to swim away from it. Attempting to swim directly back to shore against the current will only waste energy.

Instead, turn and swim parallel to the shoreline. Swimmers can either do that while they are being pulled out to break free from the current, or float with the current until they no longer feel the pull before swimming parallel to shore and then back to land.

“If you’re fighting a rip current, that rip current is stronger than you,” Greene said. “You’re not going to be moving fast at all. So you’ll be swimming in, and it’ll be pushing against you. You might be staying in the exact same location. And if you do make any headway it’s going to be very slow, and you’re going to get exhausted very quick.”

The worst thing to do if you start to get pulled out by a current is panic. Lifeguards and ocean rescue personnel stress that it’s important to stay calm.

“We don’t want people to exhaust themselves. That’s where trouble comes in is whenever people get too tired to fight anymore,” Greene said. “Whenever you’re worked up or breathing heavily, you lose your breath and you lose your energy a lot faster. So just remain calm.”

Easier said than done, but lifeguard Cliff Talbott advises those in distress to remember the main goal, staying above water.

“Try to relax as best you can. Breathe. That would be paramount,” he said. “Remember that’s your primary job. Try to focus on that.”

If you’ve been pulled out to sea and need help, Talbott said to wave your arms to get the attention of someone on shore. Emergency crews are ready to respond, and they perform cross-department training to prepare for the worst.

On Sep. 24, Manatee County Beach Patrol joined with Longboat Key Fire Rescue to perform water rescue training via boat, jet ski or from the shore. MCBP Lt. David Snyder and Greene coached rescue workers on best practices for rescuing unconscious or conscious swimmers.

Lifeguards, Longboat Key Fire Rescue workers and beach patrol were all on hand for the annual training. On-the-water training, especially with multiple agencies, is invaluable.

“We are separate agencies, but we respond together on calls. So knowing how they work, knowing how we work, knowing faces whenever we show up on a scene, it makes everything run more smoothly,” Greene said. “This is always about patient outcome and doing the best thing for our victims and our patients.”

Get the latest in news, sports, schools, arts and things to do in Sarasota, Siesta Key, Longboat Key and East County.