- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

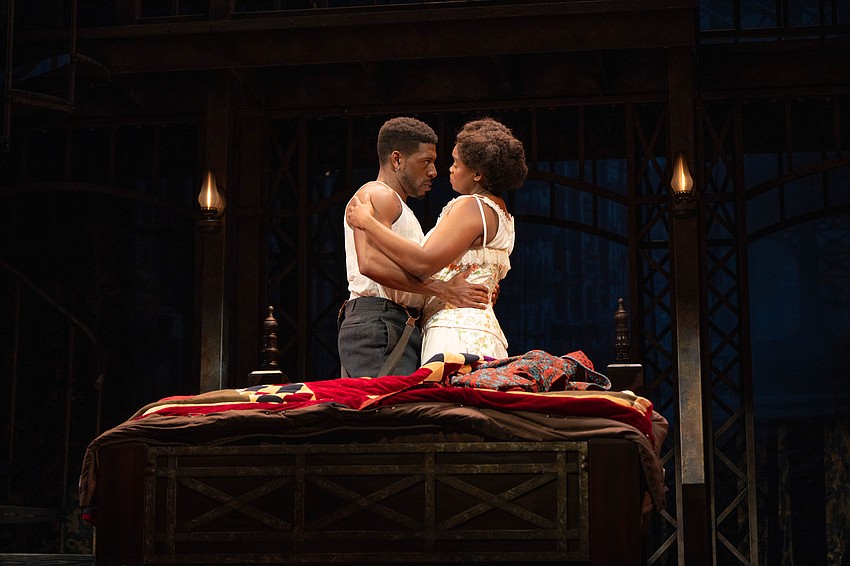

As the characters Esther and George embrace and caress each other on their wedding night in 1906 in Asolo Repertory Theatre’s production of Lynn Nottage’s “Intimate Apparel,” you can feel the audience collectively holding its breath. What’s going to happen next?

Thanks to the internet, viewers from 9 to 90 have millions of images of nudity and sex at their fingertips. Scenes of intimate human behavior that once might have been shocking have become run of the mill, even on mainstream streaming services like Netflix.

That’s not the case in the theater. It’s still a big deal for actors (especially celebrities) to take off their clothes and engage in real or pretend sexual behavior. Nudity and intimacy pack a bigger punch on the stage than on a small screen.

But who decides what actions players will take to express their ardor or even their lack of interest? That’s a question not easily answered.

Historically, a playwright would insert stage directions such as “kisses her” or “grabs him” into the play. Or a director might instruct the actors how they are supposed to behave. In other cases, it’s left to the actors to map out the intimate action on their own.

But a change has happened in these power dynamics in the wake of the #MeToo movement. There’s also been greater concern about physical contact between actors in response to pandemic precautions beginning in March 2020.

Actors are gaining what is called “agency,” control over how their bodies are handled and how they touch someone else.

Enter the intimacy coordinator.

“This is a new role for the theater,” says Summer Dawn Wallace, artistic director of Sarasota’s blackbox Urbanite Theatre and intimacy coordinator for the Asolo Rep, Florida’s largest Actors Equity theater.

“Coming out of Covid, there was an attempt to establish best practices. Theater started examining the power dynamics of putting a play together,” she continues.

As a result, a new role was defined. “The titles are intimacy choreographer, intimacy director, intimacy coordinator. Everybody’s still figuring it out,” she says.

Wallace and those who work with her agree she’s got the perfect credentials for an intimacy coordinator. She’s been an actress, director and artistic director and earned her MFA at FSU/Asolo Conservatory along the way.

To hear Wallace tell it, she’s well-equipped for her job because she’s acquainted with some of live theater’s worst practices.

“I spent half of my acting career in the buff,” she recalls. “As an actor, it’s the strangest thing to go from ‘Hi. Nice to meet you’ to being intimate with someone. You just kind of figure it out.”

The experiences of setting boundaries about what she was willing to do in roles that called for intimacy helped set the groundwork for her current position at Asolo Rep, Wallace says.

The obvious question is: Doesn’t the new role of intimacy coordinator encroach on the territory of other key participants in a theatrical production, namely the director and the actors?

It depends on who you talk to. Curtis Bannister, who plays the role of the bridegroom George, an immigrant from Barbados, in “Intimate Apparel,” says at first he wasn’t sure that having an intimacy coordinator would be a good thing.

Bannister, who has worked with intimacy coordinators in Chicago and Washington, D.C., in addition to his experience at Asolo Rep, initially thought that “having someone in the rehearsal could get in the way of exploratory actions. I thought it would inhibit the action.”

Now, Bannister sees the value of an intimacy coordinator because all actors don’t have the same background. “When you’re going to be having intimate moments, my comfort level may be different than my partner’s, especially if they come from a background with sexual trauma. The intimacy coordinator creates a safe space,” he says.

Aneisa Hicks, whose character in “Intimate Apparel” is an independent Black seamstress with little or no sexual experience, says she never had any second thoughts about having an intimacy coordinator become part of a play.

Says Hicks: “Many of those people in the older generation who didn’t grow up with an intimacy coordinator may say it inhibits them. They are bothered by guard rails. My generation and younger like having an intimacy coordinator because there are too many stories of people using intimacy to harass somebody.”

She adds, “For too long, if somebody crossed a line they could fall back on, ‘I was caught up in the moment.’” Not anymore.

Asolo Rep Associate Artistic Director Celine Rosenthal says she recruited Wallace to become the company’s intimacy coordinator in order to systemize processes that had been evolving.

“We started doing this before 2020 and the #MeToo movement, but we didn’t necessarily have it on every production,” Rosenthal says.

When Asolo Rep’s new producing artistic director, Peter Rothstein, joined the company last year, the process became more formalized, she says. For “Inherit the Wind,” Asolo Rep had Wallace do a consent workshop with the cast. She also worked as intimacy coordinator on “Dial M for Murder,” which Rosenthal is directing.

“We had Summer Dawn work on all the shows. It was an interesting catalyst. She makes sure setting boundaries is more systemized, as opposed to bespoke,” Rosenthal says.

Audiences of FSU/Asolo Conservatory plays have also seen the fruits of Wallace’s work in such recent productions as “Miss Julie” and “Clyde’s.”

How does it all work? At Asolo Rep, it’s as simple as using a stoplight system of red, green and yellow to signal what’s acceptable to an actor when the scene is “blocked,” or the movements mapped out.

Then actors are required to check in with their scene partners prior to every production with a private sign such as a fist bump or nod to acknowledge their consent for that day.

Actors are free to tell the director and fellow cast members that certain parts of their body, say their hair, are off limits under any circumstances, says Rosenthal. The reason could be as mundane as an actor having a bad hip from an injury, she says. “It’s a lot like fight choreography.”

Not all directors who have come to Asolo Rep are enthusiastic about having an intimacy coordinator. “There’s a fear that it will make the process clunky,” Rosenthal says. “But Summer Dawn is skillful at setting up that space. The folks who have been reticent at first changed their minds.”

As a director herself, Rosenthal says she finds working with Wallace “enormously freeing. It’s still my vision for the piece; I merely have another collaborator. It’s like working with a choreographer. I consider it enhancing, not encroaching.”