- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

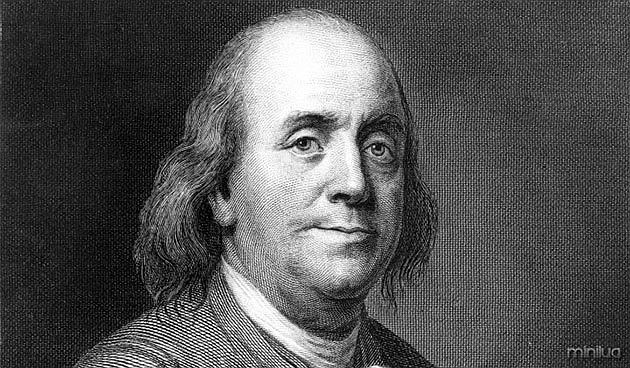

Ben Franklin, where are you?

Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic Party presidential candidate, tweeted on June 23: “Forget death panels. If Republicans pass this bill, they’re the death party.”

Donald Trump, during the 2016 election campaign, called her “Crooked Hillary.”

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., described the Senate health care bill as “blood money. People will die … Senate Republicans were … dreaming up even meaner ways to kick dirt in the face of the American people and take away their health insurance.”

And then there was the technology chairman of the Nebraska Democratic Party, commenting about Republican U.S. Rep. Steve Scalise, who nearly died after being shot by a rabid anti-Republican Democrat: “His whole job is to get people, convince Republicans to f---ing kick people off f---ing healthcare. I hate this mother---. I’m glad he got shot.”

Eric Trump calls the chairman of the Democratic National Committee on FoxNews a “nut job.”

Johnny Depp … Kathy Griffin … Shakespeare in the Park … The list goes on and on.

So it is. On the eve of the day 56 members of the Second Continental Congress ratified and signed the Declaration of Independence — pledging to each other their lives, fortunes and sacred honor; and declaring liberty and renouncing tyranny — on the eve of the day Americans will celebrate the 241st anniversary of the birth of what has become the greatest democratic republic in history, we are ripped apart. A strongly woven garment ripped jaggedly at the seams, with the perpetrators standing opposite one another gripping serrated knives.

This is not right. We should be feeling patriotic. We should be feeling proud to be an American, proud of the values we have pursued and cherished for two and a half centuries — that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” As a friend said recently: “To be an American is to win the lottery of life.”

But for eight intense months, we have seen and felt hatred, a molten, volcanic ash spewing everywhere, our nation deteriorating and descending into an uncivil war. Actually, another friend told me recently: “I think we are in a civil war and don’t know it.”

There are many catalysts for this cauldron — an amalgamation over decades of deteriorating social, cultural and political mores. But these enzymes converged, convulsed and blew after the 2016 presidential election — and let’s be honest — when the core of the Democratic Party refused to accept that American voters elected Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton.

To make it worse, the biases of the New York Times, Washington Post and national television news networks have fueled the hatred to a level that none of us in four generations has experienced such vile and vitriol in the public square.

This is why we said: Ben Franklin, where are you?

In his day, at the time of the American Revolution, as a signator of the Declaration of Independence and later the U.S. Constitution, Franklin was widely regarded as the sage of America. He was the young nation’s chief advocate, example and leader for good citizenship. He defined good citizenship — in his actions and his prolific writing.

As a citizen of Philadelphia, he was constantly at the forefront of efforts to make it more livable. He led efforts to install pavement and bricks to help get rid of the sludge that covered the streets. He used his newspaper to raise funds for a Philadelphia hospital. He created the nation’s first volunteer fire company, which led to the creation of the first insurance company to protect homes against fire.

But the way Franklin behaved and wrote about the virtues of good citizenship set him apart. Under such pseudonyms as Silence Dogood, Busy-Body, Alice Addertongue, Obadiah Plainman, Homespun and Poor Richard, he communicated to the common citizen about the importance of character and virtues — crucial, he believed, for the new nation’s form of government to succeed.

He especially focused on this after the Revolutionary War. This was when Franklin penned his 13 virtues by which to live in his “Autobiography.”

Go down the list. While Franklin targeted these virtues at the common man, apply them today. They are apropos for everyone — especially so for our national elected leaders and the media. Indeed, instead of incessantly looking for ways to tear down, excoriate, ridicule and incite extremes, for Franklin, virtue and morality meant doing good to one’s fellow man.

“One Man of tolerable Abilities may work great Changes,” Franklin wrote in “Autobiography.”

His was a life of that. By living the virtue of humility, Franklin practiced a leadership style of dignified persuasion. In a 2013 essay for the Heritage Foundation, Steven Forde, a political science professor at the University of North Texas and Franklin scholar, wrote:

“One of Franklin’s earliest lessons … was that a contentious or imperious style is self-defeating. Rather than persuading men, it offends their pride and accomplishes nothing.”

Franklin learned, Forde wrote, “that his public-spirited proposals often encountered resistance rooted in envy. No matter how beneficial the project, some would refuse to follow if they thought it would elevate the leader above the rest. Franklin therefore began to present projects as the initiative of ‘a number of friends’ or ‘publick-spirited Gentlemen,’ even if the initiative was wholly his. This greatly smoothed the way by removing the issue of personal credit or honor.”

With this practice, he formed the “Club for Mutual Improvement,” called the “Junto” — his 10 most intelligent friends. They discussed morals, politics and philosophy. Club rules forbid abrasive chiding or personal attacks — the kind of behavior that is so commonplace in today’s public square, on television and throughout social media. Virtually nowhere can you find examples of Franklin erupting into public tantrums or vitriolic or demeaning commentaries.

Franklin, far wiser than most, knew the fragility of what the Framers created. He warned that only a citizenry with the proper temper can support a free government. That’s why, when asked once what kind of government he and the Framers created, Franklin responded: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

Ben Franklin, we need you now.