- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It’s never silent.

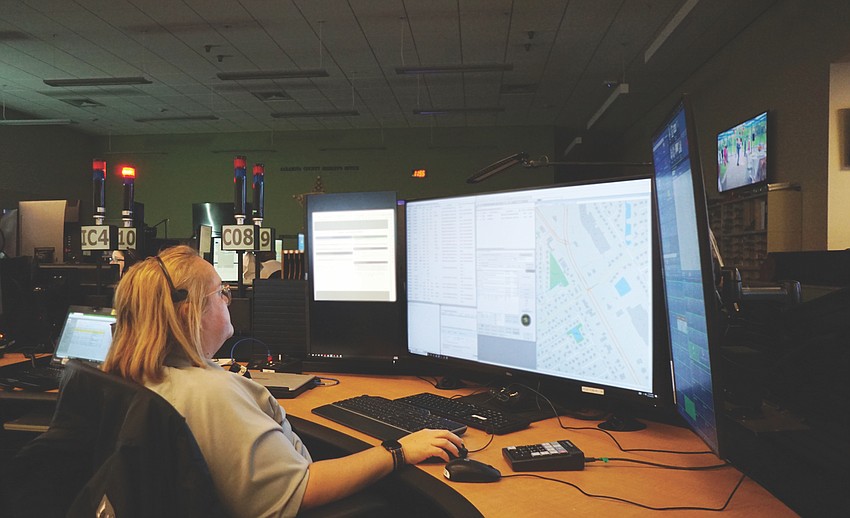

Walking into the Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office Emergency Operations Center is like stepping inside the air traffic control center of a busy airport, with screens, maps, and headset-wearing staff all around.

Sirens in different tones sound every few seconds, keyboards are constantly clacking, and then there's the voices. "911, what is the location of the emergency?" "911, what is the location of the emergency?"

Operator Tia Brand started in the fire dispatch pod at 3 a.m., picking up some overtime before her regular shift starts at 7 a.m. By 8 a.m., she’s warmed up.

Brand focuses on fire dispatch for north Sarasota. Her territory is from University Parkway to Stickney Point. The dispatcher to her immediate right, Pam Manning, is on break, so Brand is also covering her territory.

Early in the day, fire calls aren’t usually pouring in. The afternoons can get busier, though.

“Fire is either crazy busy, or it's nothing,” Brand says.

Shortly after Manning gets back from break, a robotic voice from the computer states, “Fire.”

A call needs to be dispatched.

It's in Manning’s territory, but it’s possible that power lines are involved. Someone needs to call Florida Power & Light — Brand is on it.

The first try isn’t answered. Brand tries again. No luck.

Josie Lopez, a newer dispatcher, tries her hand at getting a hold of FPL. No luck.

Brand keeps trying, but then Manning gets word it’s a phone line, not a power line. Everyone goes back to their own screens.

“Fire pod is really a team effort for sure,” Brand says.

Shifts are 12 hours long, but there’s always a lot of overtime available. The department remains understaffed, by about 22 people.

Brand says she usually has one day off a week. She doesn’t mind the overtime pay.

Brand never imagined growing up in Englewood that she would be in this career. After graduating college, she saw an ad in the paper for a dispatch job and applied.

She’s been here 14 years now.

Manning, one of her “pod partners,” has 22 years under her belt. Lopez is going on about five years at the call center.

But it’s not as easy as applying, getting the job and taking the calls. There’s a one-month academy for new recruits, followed by three months of floor training.

Everyone in the fire pod agrees that five years is usually the threshold — if dispatchers can get past the first five years they’re usually in the career for good.

A big part of dispatching for law enforcement is making sure the officers going on calls are safe.

The screens at fire and law enforcement dispatch look almost identical — the main difference is the type of calls coming in.

To the far left of the dispatchers is a screen with all radio frequencies for the territory that the Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office covers. There are at least two dozen, but Brand can identify each like second nature.

Incoming calls show up in identical fashion to how they do in fire. The calls appear, Brand looks at the nature of the call, and finds the right unit to respond.

Calls that flash blue are high priority — this could mean violent crimes. For those calls, Brand said the dispatchers send a more emphasized call tone to let the responding officer know it’s urgent and to take precautions.

The other part of law dispatch is checking in on officers in the field.

Shortly into Brand’s shift at law dispatch, an officer calls in a traffic stop. He gives his location, a description of the vehicle and the license plate number.

Every five minutes after an officer either responds to a call or calls in a traffic stop, dispatchers request a “10-74.” The purpose is to check the officer’s status, to make sure they’re okay.

If the officers respond with “10-4,” that means they’re all good and don’t need further checks. But if they respond with another “10-74” it means they’re still okay but want the dispatcher to continue the five-minute checks.

Around 10 a.m., an officer calls in a check on a suspicious person. The call comes in broken, so Brand asks the officer to repeat.

Diction in fire and police are different, Brand says.

Law is usually faster, and more mumbled. It takes some experience to make out what the officers are saying on the first try.

At 10:16 a.m., a call comes in about a fight at tennis courts in Sarasota. The report says it's a physical altercation. Multiple units respond.

Minutes later, a medical call on Longboat Key comes across the law dispatch screen. On Longboat, all medical calls also get police dispatched.

Two units on Longboat were busy, so Brand tries calling the on-duty sergeant over the radio. There’s no immediate response, and Brand is about to call the sergeant’s phone when one of the units becomes available.

Brand sends that unit to the medical call.

Seven hours into a shift, Brand is alert and rapidly clicking between screens, sending the appropriate help.

She’s on top of her game. A good amount of coffee helps too, she says.

Sometimes shifts are longer than 12 hours with overtime, which Brand said she takes quite a bit. But shifts are easier to manage with a break every two hours.

“I like my job,” she says. “I like helping people.”

More than just helping people, she finds the job is most rewarding when the people appreciate the help.

Brand also enjoys helping new people on the team and seeing them progress. Soon, she says, she might go back to being a part-time training officer.

“It’s rewarding to help people and get them doing the job I love to do,” Brand says.

Brand spent a couple hours taking calls, both emergency and non-emergency.

The busiest time is between 7 and 11 p.m. After that, it’s not too hectic the rest of the night, Brand says.

Starting at 11:10, she picks up a non-emergency call for a citizen to report a possible burglary.

For each call that comes in, call-takers input the situation type in the report. Then, on a screen to their left, an auto-generated question list appears.

Brand and other workers said sometimes people on the other line get frustrated with all the questions. It’s understandable, the dispatchers said, because the person having an emergency usually just wants help as quickly as possible.

“There’s a reason for all the questions we ask,” Brand says. “It’s very important.”

If the situation is in progress, there’s a greater amount of questions, and different ones than if the situation has occurred in the past. If the situation deals with a suspect, there are different prompts for if the suspect has left the scene or if the suspect is still around.

It’s important to ask all the questions and in the order they appear, Brand says. The questions help call-takers get all the important information to share with responding agencies.

Address verification is another important aspect of taking calls. The address is taken at the start of the call and then asked to be repeated at the end.

“What’s the nearest cross street,” is one question that some callers have difficulty with, but it helps pinpoint and verify an exact location.

Call-takers may also ask many questions as to the city, apartment number, lot number, entrance or what area inside a store.

Getting an exact location is important, not only for responding agencies to know where to go, but also for their safety.

Brand takes another non-emergency call around 11:30 a.m. It’s someone asking if the department offers service hours. Brand gives the caller the number for the exact department to contact.

All the calls are taken equally seriously, and the call-takers try to give help whenever possible.

As noon approaches, Brand takes another short break. She still has about seven hours left in her shift: a 12-hour shift.

There’s no real “lunch break” per se. Everyone in the call center gets a 20-minute break every two hours.

There's a few ways to de-stress after exceptionally difficult calls.

Some laptops in the pods play calming videos: three-hour YouTube loops of soothing marine life scenes or puppies falling asleep.

In the dispatch break room there's a massage chair, apparently contributed by Longboat Key Fire Rescue Chief Paul Dezzi.

Dezzi is like a celebrity within the fire pod. The four dispatchers working talk about the massage chair, ask who has taken which training with him and swap stories of meeting him.

No job in the call center is easy, but the fire pod says there’s one thing that makes or breaks a person.

“It’s a job where you have to get used to not knowing the outcome,” Lopez says.