- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

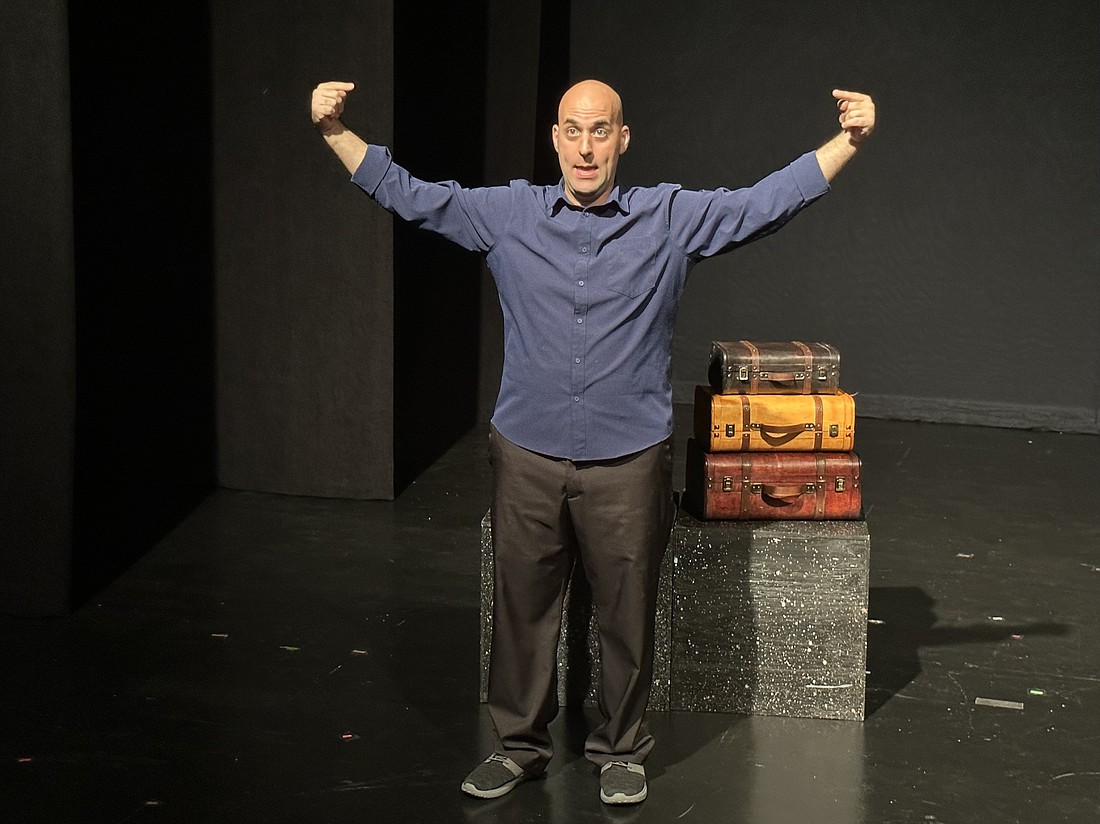

Stop me if you’ve heard this one. “Clowns Like Me” is premiering this month at FSU Center for the Performing Arts. Scott Ehrenpreis is starring in the lead role. Actually, it’s the only role.

It’s a one-man show; Ehrenpreis is the man in question. He’s playing himself. The play’s about his life, but he’s not the author. Director/playwright Jason Cannon wrote the script, distilled from hours of anecdotes and stories he’d absorbed hanging out at the actor’s home. Why go to all that trouble?

Because the actor’s story was worth telling.

According to Cannon, “Clowns Like Me” is a character study. (Strictly speaking, a character study of a character actor.) It’s what Ehrenpreis does. And he’s very good at it.

He’s played a dimwitted boy-toy in “Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike,” a high-strung TV technician in “Network,” a hardboiled police reporter in “The Front Page” and a bullying Little League baseball coach in “Manager.”

I’d seen the actor’s shape-shifting talent on stage. But I didn’t see the mind-war inside him.

The actor’s father, Joel Ehrenpreis, saw it every day. He was close to his oldest son. Scott Ehrenpreis has waged a lifetime battle with OCD, bipolar disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, social anxiety and depression.

There was nothing to do but keep fighting. One day, the father made a suggestion to his son: “You’re an actor. Telling engaging stories is what you do. Why don’t you tell your own story?”

Scott Ehrenpreis loved the idea. And he tells his story in “Clowns Like Me.”

It isn’t a vanity project. It’s a survival strategy. And a call to action.

But a one-man play isn’t a one-man job.

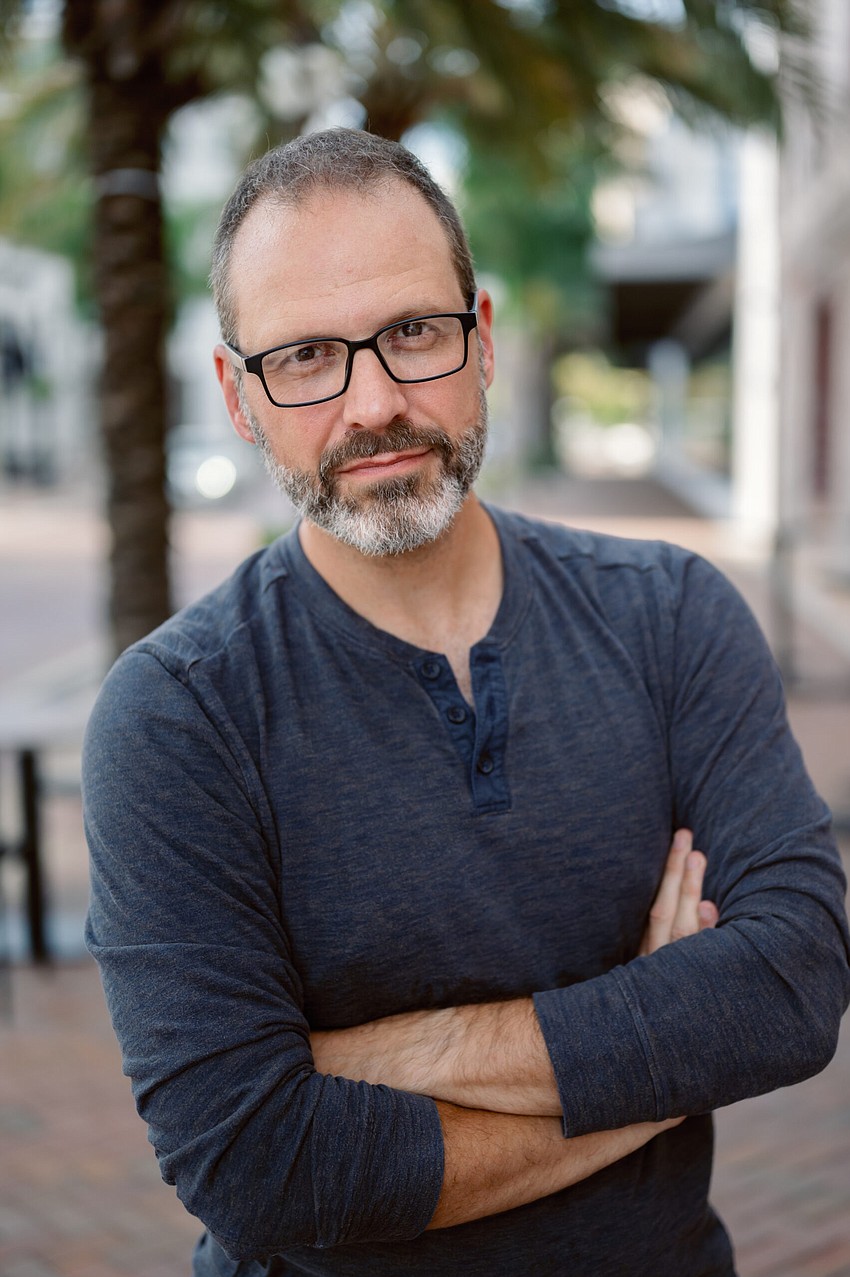

The father-son team had many talents. But writing plays wasn’t one of them. So they sent out a call to the local theater community. Florida Studio Theatre veteran Cannon answered.

“This project basically fell in my lap,” Cannon says. “The three of us met — and we just clicked. Once I understood Scott’s story, I felt compelled to help him tell it.”

During that first brainstorming session, the young actor bubbled with funny, touching anecdotes. Cannon knew they didn’t add up to a play. He had to find the Big Story that tied all the little stories together. He wasn’t worried. Cannon had done this before.

To tell the man’s story, the playwright had to get to know him. And that would take time.

“I spent the first few months pulling stories out of Scott,” Cannon says. “I’d go to his condo a lot. No timetable, no pressure. He’d talk, I’d listen. I got to know how Scott lived, what he’d been through. I also talked to his parents and other people who knew him in different phases of his life.”

The young actor’s stories hit him with a revelatory punch. The impact reminded Cannon of Mike Birbiglia’s, Hannah Gadsby’s and Chris Gethard’s stand-up comedy. These comedians all had mental health issues.

Very different struggles. Very different stories. But a similar approach. “They all work in the intersection of storytelling, stand-up comedy and one-man theater,” Cannon says. “They’d all found that sweet spot. I knew that’s where we had to go.”

OK. Just do what Birbiglia, Gadsby and Gethard do! That's a cakewalk if you’re a stand-up veteran. If you’re an actor or a director, it’s a long hard road.

That road included a stint at boot camp. Not the one on Paris Island, but Comedy Boot Camp at McCurdy’s Comedy Theater.

Ehrenpreis is a great actor. Wouldn’t his skills make him a great comedian? Cannon shakes his head no.

“Stand-up is a very different skill set,” he explains. “You break the fourth wall; you open yourself up; you directly address the audience. Scott lacked those skills. As an actor, he didn’t need them! In scripted theater, that’s not the way it’s done. To perform the play I had in mind, he’d have to learn how.”

Cannon stresses that “Clowns Like Me” isn’t improv. There’s a script, and he wrote it. But it’s written in stand-up style, with audience interactions. To do it right, Ehrenpreis would have to master the not-so-gentle art of stand-up.

Makes sense. But why would a playwright need stand-up skills?

“Because Scott needed a buddy,” he says. “I’d done improv at FST — and taken McCurdy’s Comedy Boot Camp course before. But it’d been awhile, and my skills were rusty. A refresher course couldn’t hurt.”

Actor and playwright took McCurdy’s crash course in stand-up. Three days. Twelve hours. Both earned their comedy black belts. Then the play’s development process kicked into high gear.

Cannon polished “Clowns Like Me” over a series of drafts. He would perform the latest draft for a live audience. What gets a laugh? What falls flat? Based on audience feedback, Cannon would fine-tune the work-in-progress. The actor would then perform that version. Rinse and repeat. Five times.

At the end of nine months, Cannon finally had a play on his hands. “That’s normal for a baby,” he laughs. “It’s pretty quick for new play development.

“Clowns Like Me” hasn’t opened yet. Lacking a time machine, I haven’t seen it. But I have read the script. I like it. Cannon’s a damn good writer. And he gets to the heart of the actor’s story.

Ehrenpreis doesn’t whine. His one-act play isn’t a poor-me story. He owns his mental illness, but doesn’t let it define him.

The play’s not a diagnosis. It’s an introduction. Meet Scott Ehrenpreis! He’s large; he contains multitudes. Simply put, he’s a person. After seeing the play, you’ll get to know that person. But you have to see the play.