- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Back in the 1970s, at the height of the American Indian Movement, it wasn't unusual in places near reservations to see bumper stickers and T-shirts emblazoned with the words "You Are On Indian Land."

While it could be argued that the slogan applied to the entire United States, it is certainly true in this part of Florida, where the Seminole tribe was forcibly removed from its land during three wars with the U.S. government. Today, many descendants of those Florida natives live in Oklahoma.

With the 2016-17 protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, the movement for indigenous rights picked up steam again. Members of 200 Native American tribes gathered together for the first time in 150 years, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

The next year the John and Mable Ringling Museum hired Ola Wlusek as curator for modern and contemporary art. A former public art coordinator for the city of Calgary and curator at the Ottawa Art Gallery, Wlusek was the driving force behind the Ringling's exhibition, "Reclaiming Home: Contemporary Seminole Art," which runs through Sept. 4.

Can you draw a straight line from the Standing Rock protest to the "Reclaiming Home" exhibition? Not exactly, but they both signify a growing awareness of Native issues.

If you haven't seen the Ringling's ambitious, wide-ranging show in the cavernous Ulla R. and Arthur F. Searing Wing, make time to do so. The colorful, multimedia art works are profound and arresting. Like the circuses that generated the wealth that built the museum on Sarasota Bay, "Reclaiming Home" has something for everyone. It's family-friendly to be sure.

Descriptions like "ground-breaking" and "awe-inspiring" are not hyperbole for an exhibition that was five years in the making.

Hundreds if not thousands of hours of discussion and consultation paved the way for "Reclaiming Home." Some of Wlusek's travel and research was underwritten by a curatorial research fellowship she received from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

"Reclaiming Home" was made possible by loans from leading Native American cultural institutions including the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, both in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Last but not least, art and advice was lent to the Ringling by the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum on the Big Cypress Seminole Indian Reservation.

The exhibition is accompanied by a handsome catalog with thought-provoking articles by its artists.

Museums have come under fire in recent years for acquiring or accepting donations of looted relics. They have been forced to return antiquities to their original owners, including governments and tribal nations. Since nearly all of the artwork in "Reclaiming Home" is loaned, that isn't a concern here. But the Ringling show takes place at a time when museums and other cultural institutions are being questioned about their practices and even their existence.

The pressing issue here is whether the Ringling can live up to its lofty goal of allowing the Seminoles to reclaim, if not their home, their identity. Of course, the Sarasota museum cannot erase the history of colonialism and the ramifications of the policy of Manifest Destiny that pushed the American frontier across the country to the Pacific Ocean.

It cannot restore to their original owners the native lands now occupied by condos, shopping centers and highways. It is ridiculous to think that art can right these kinds of wrongs.

What the Ringling has achieved with "Reclaiming Home" is to provide for the first time within its halls a forum for the telling of Seminole stories through authentic Native art.

One can't help leaving the museum with thoughts and images of ghosts that lurk among the 100 pieces of art by 12 artists of Seminole, Miccosukee and mixed heritage.

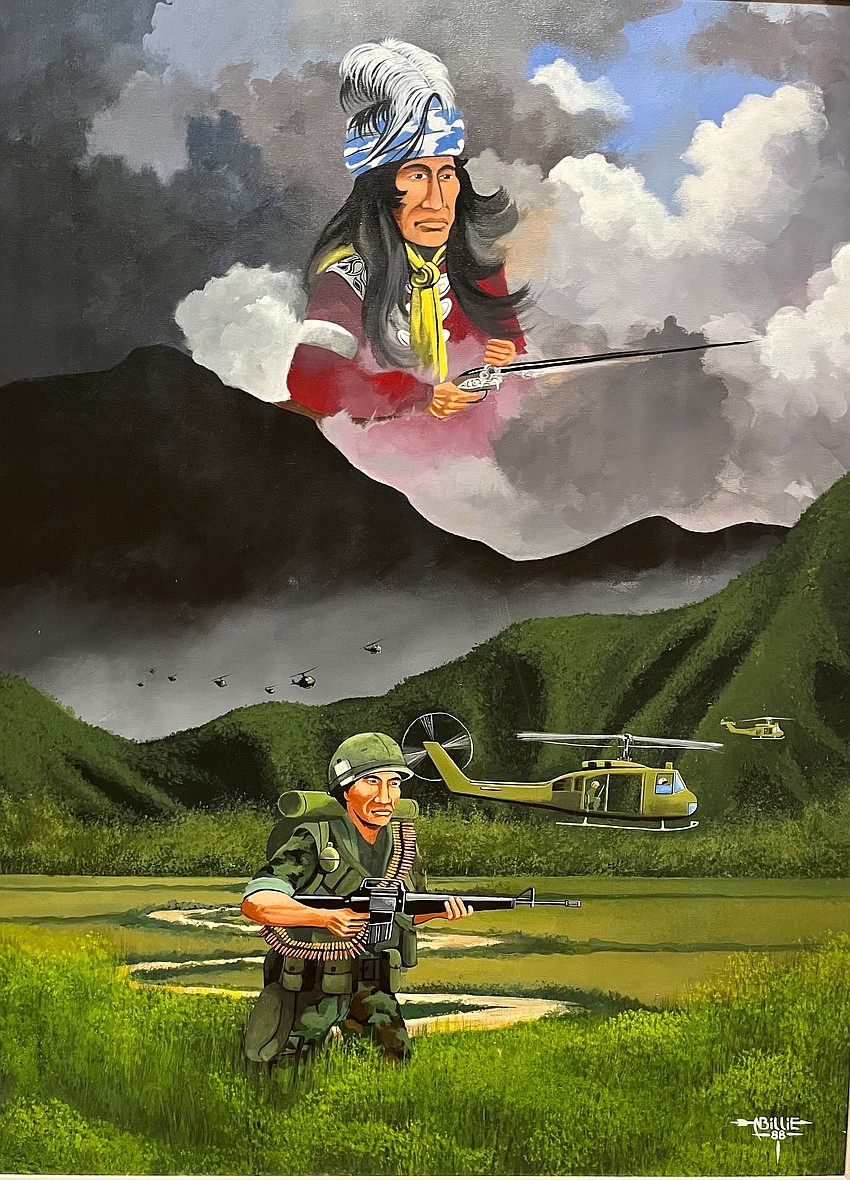

One of the first ghosts a visitor sees upon entering the Searing Wing is a painting with a native American warrior in full regalia holding a rifle. He's hovering in the clouds above a young soldier fighting in a jungle, presumably Vietnam.

Noah Billie, the artist who painted the acrylic work "Untitled," in 1998, was traumatized by his wartime experience, Wlusek said in a recent gallery talk. Upon returning from Southeast Asia, Billie isolated himself and didn't speak. Creating art helped heal his psychic wounds, she said. Considered to be one of the most influential Seminole artists in Florida, Billie died in 2000.

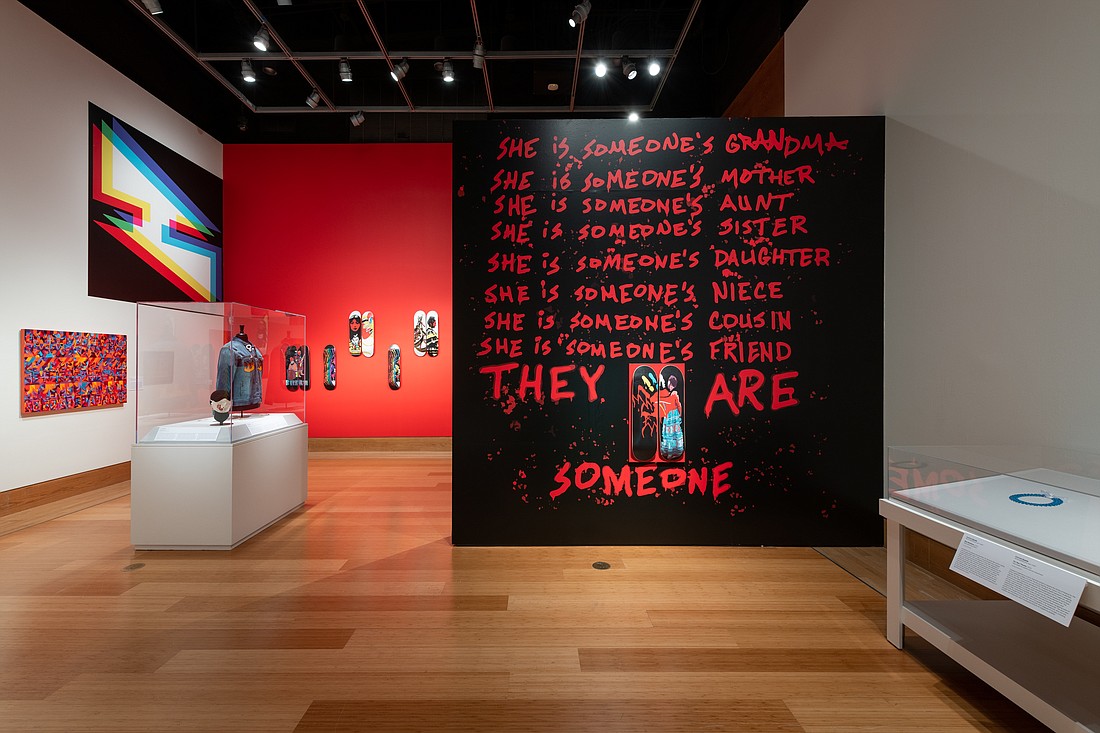

Phantoms are also invoked by a big, graffiti-inspired installation in red and black in the exhibition. Wilson Bowers pays tribute to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women with the stark piece, which ends with the words, "They are someone." According to the University of San Diego, there are at least 23,000 people missing from tribal lands in the U.S., mostly women, but most experts feel this number is much higher.

In 2021, President Biden declared May 5 “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day" to shine light on the matter, which is also a widespread problem among Canada's First Nations.

A thrilling sense of martial speed is evoked by Bowers' brightly painted skateboards on the walls of the Ringling. It took strength for Pedro Zepeda, who is Seminole and Mexican, to carve the canoe on display in "Reclaiming Home" from a cypress log using the same tools and methods that have been employed by the Seminoles for at least 200 years.

According to a video narrated by Zepeda that is streaming in one of the gallery's nooks, the Seminoles adopted metal tools after they were introduced by Europeans.

Feminine energy is also in evidence in "Reclaiming Home." Ruffles, tiers and rick-rack embellish the dresses worn by Seminole women depicted in paintings as well as costumes on display. One elaborate outfit was made specifically for the "Reclaiming Home" exhibit, says Wlusek, by artist Jessica Osceola, who imagined what she would wear to the opening of the show.

Artist Elisa Harkins uses images and sound to capture the Native songs that the exiled Seminoles sang to lift their spirits as they traveled the "Trail of Tears" from Florida to Oklahoma. Harkins, who is of Cherokee/Muscogee/Creek descent, also preserves Native culture by creating costumes and taking photographs.

If there is one piece of art that can lay claim to being the set piece of "Reclaiming Home," it is "The Last Supper," C. Maxx Stevens' multimedia installation of a table laden with replicas of sugar-filled goodies. This cornucopia of cakes, cookies and the like is a monument to those who have perished from diabetes.

Strewn underneath the table are shoes, canes and crutches, reflecting the loss of mobility and amputations suffered by many diabetes victims before their ultimate death.

"The Last Supper" is a moving reminder that unhealthy food has taken its toll on Native Americans, including the Seminoles.

In the face of such devastation, is it possible to leave "Reclaiming Home" with any hope? It is.

Just look at the work and life of Jessica Osceola. (There is more than one Osceola in the show.) The Seminole/Irish artist grew up in her great-grandmother's Seminole village in Florida and today owns a microfarm and a studio in Naples.

A 2008 graduate of Florida Gulf Coast University, Osceola holds a master's degree in fine art sculpture from Academy of Art University in San Francisco. Osceola has compiled her life story and art into a book, "We Will Always Be Here: Native Peoples on Living and Thriving in the South."

Her 2017 work, "Portrait One, Portrait Two, and Portrait Three," recently became the first work by a Seminole artist to be added to the Ringling's permanent collection.

It's been 167 years since the Seminoles were forcefully relocated to Oklahoma, but the art of Florida's original residents is finally getting the attention it deserves in their homeland.