- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Alison Yawn, a kindergarten teacher at William H. Bashaw Elementary School, was working with three students at a small table in the back of her classroom.

She would point to a letter on a card with the alphabet on it and have each student say all the sounds each letter makes. That would be followed by the students naming the object in the picture that accompanied the corresponding letter.

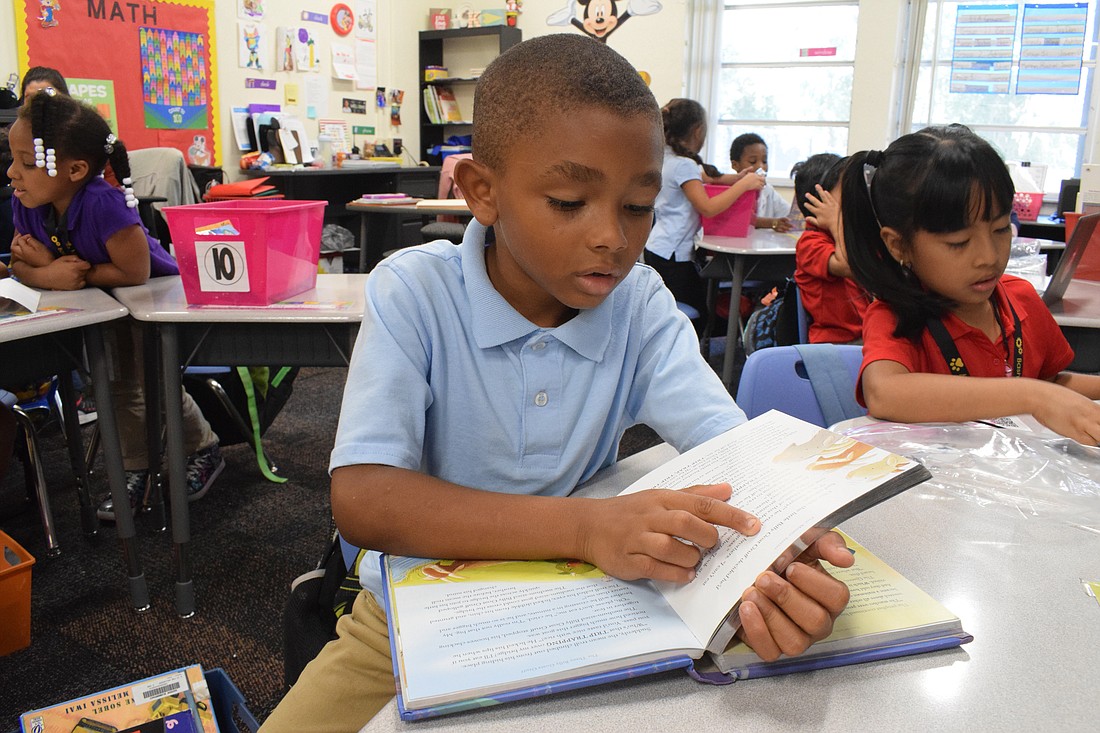

Meanwhile, in another kindergarten class at Bashaw, half the class was reading while the other half was completing literacy activities on their computers.

The focus on reading has increased at Bashaw Elementary students in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade as the School District of Manatee County pilots its EarlyBird Screener program.

From Nov. 28 to Dec. 22, students in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade at Bashaw, Blackburn and Prine elementary schools will participate in the 45-minute screener that flags students who might be at risk for dyslexia based on specific literacy subtests within the EarlyBird screener.

Alison Nichols, the interim director of elementary curriculum and instruction for the school district, said the screener not only will help teachers and paraprofessionals identify potential students with characteristics of dyslexia but also identify students’ strengths and weaknesses in reading.

“Each of the subtests are targeting different literacy skills,” Nichols said. “So it’s things like letter naming, letter sounds, anything around phonological awareness. Then the screener assesses those key literacy skills."

He said the screener will help make predictions about the student's future reading success, including whether the student will be reading at the current grade level by the end of the school year.

The earlier the district can identify and remedy literacy gaps, the better, Nichols said.

“There’s all kinds of studies out there that show us the earlier we intervene, especially when we’re talking pre-K, kindergarten and first grade, then they’ll have significantly fewer problems in learning to read at grade level,” she said.

The subtests, which will be completed all at once in 30 to 45 minutes depending on the grade level, are like a game, Nichols said. When students log onto the screener, it will look like a game board, and students will click on the different subtests as if entering different lands in the game.

Nichols said students most likely won’t realize they’re being tested because it will be as though they’re playing games.

The window for testing the entire grade is nearly a month because screening must occur in small groups in quiet spaces as there are speaking components. For example, a student will be recorded to analyze how he or she is pronouncing words and reading aloud.

“We’re trying to minimize distractions so we can get as accurate results as we can,” Nichols said.

Nichols said certain subtests are more aligned with the risk flags for dyslexia, such as difficulty with accurate and fluent word recognition, poor spelling and deficits in phonological awareness.

Although teachers and paraprofessionals might see risk flags for dyslexia after analyzing the results of the subtests, Nichols said that is not a diagnosis, and the district, under law, cannot diagnose a student with dyslexia.

The district will send a written response to the parent so the district can have a conversation with the parent about the screener, what it does and the data collected. Then the teacher will explain what is being done in the classroom to help and what can be done at home.

If the parent chooses, the parent can request a comprehensive evaluation for the student through the district or take the student to be medically diagnosed.

Nichols said the screener can be a resource to help all students regardless of whether they see risk flags for dyslexia.

“It’s helping inform teachers which particular skills a student might need work on and which fields a student has that are strengths,” she said. “Overall, it’s giving us an accurate picture of where a child is with literacy.”

Once screenings are complete, teachers and paraprofessionals will gather in January for a professional development on analyzing the data from EarlyBird. Teachers and paraprofessionals will learn how to discuss the data with parents. They’ll have the opportunity to see what resources are available to help students and learn how they can adjust their lesson plans to better suit the needs of students.

For example, teachers might have students look into a mirror to see how their mouths should look into order to form a certain word or sound.

“We would want to hit all the different learning modalities, including visual, auditory, kinesthetic and tactile, to get in that multisensory instruction, which has been shown to help students who have cognitive reading disabilities,” Nichols said.

In April, students will be screened once again to show the progress made. All the data will be collected and analyzed and then passed onto the student’s next teacher to provide continuity of instruction.

Nichols said sharing data with a student’s teacher the following year will be crucial to tracking a student’s progress.

“Let’s say a child leaving kindergarten had one of those risk flags,” Nichols said. “they’re going to first grade and right as they walk through the door, that first grade teacher already knows what this particular child needs and from day one, can adjust instruction so we’re not losing time.”

Nichols said the screener can assist in ensuring the district is providing a solid foundation in literacy that will ultimately help students as they continue in their education.

“There are studies out there that show students who are poor readers in third grade remain poor readers in ninth grade because they’re not getting that structured literacy instruction early,” she said. “If we can get that foundation going really well and we can fill in gaps or not have gaps right away starting in pre-K, it means that hopefully we’re moving kids all the way up through high school reading on grade level, and they’re going to graduate.”