- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

The landmarks are all over the region.

From the Sarasota Opera House renovation to Waterside Place in Lakewood Ranch, to Patriot Plaza at the Sarasota National Cemetery to The Lodge in Country Club East.

More are on the way, including the Mote Science Education Aquarium, the Lakewood Ranch Library, Marie Selby Gardens Masterplan, and the Ringling College of Art and Design New Dining Hall.

But when the shareholders of Willis Smith Construction talk about 50 years of success, they don't tell stories about the impressions made by the company with its brick and mortar work.

Their conversation focuses on people.

As Willis Smith gets set to celebrate its 50th anniversary on June 6, every story about building projects was preceded by a tale about a fellow employee.

For instance, the trip to Breckenridge, Colorado in 2005 by company executives.

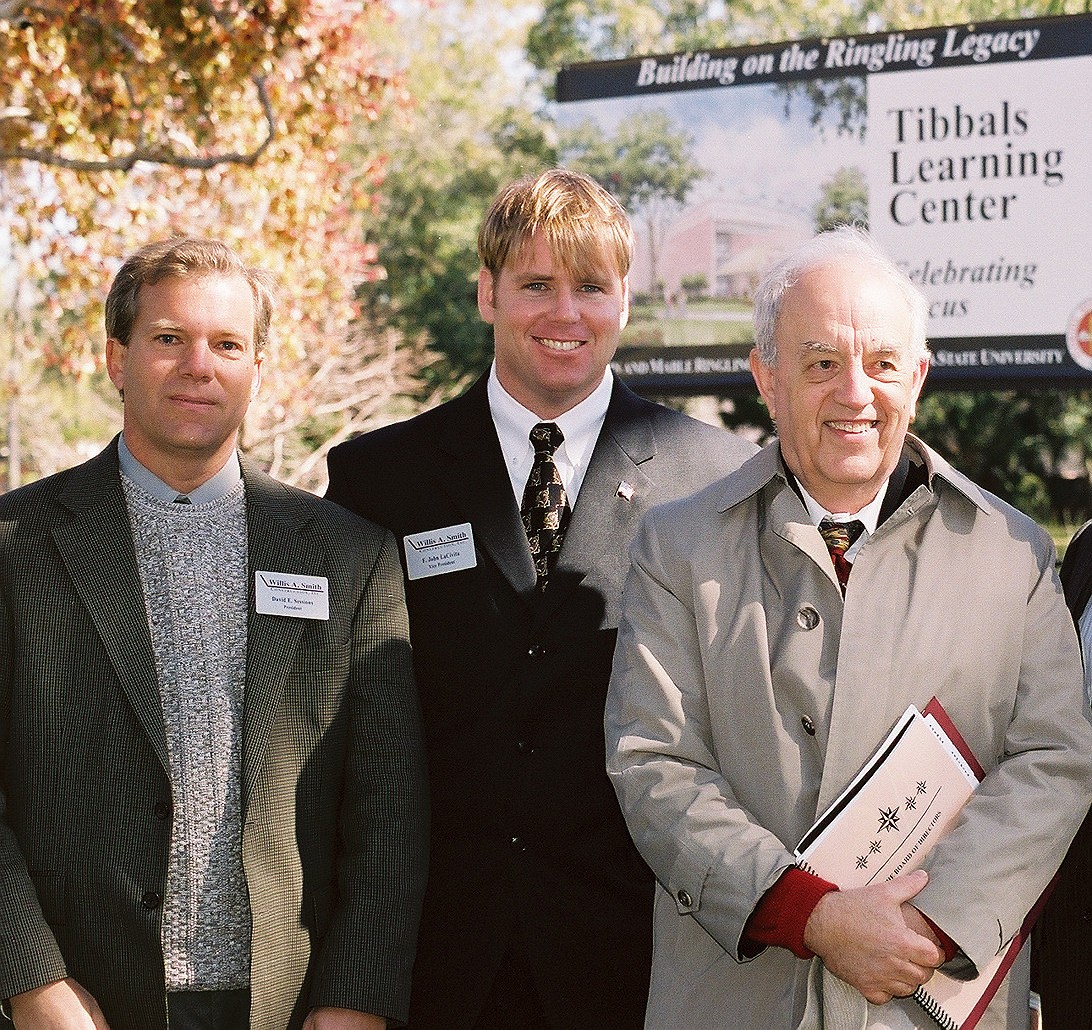

For some background, majority owner David Sessions and then Vice President John LaCivita began organizing company trips for the project managers in the mid-1990s with the thought it would promote bonding. Since most of the executives loved skiing, the company rented a vacation home in Breckenridge.

On the 2005 trip were four impressive young executives — Taylor Aultman, Nathan Carr, David Otterness and Brett Raymaker — who eventually became minority shareholders. Admittedly, they were young 20-somethings fresh out of the University of Florida's construction management program who were all about having fun.

While most of the project managers loved skiing, Nathan Carr enjoyed snowmobiling, and he convinced Raymaker and Aultman to join him.

"He told me not to get the insurance (on the snowmobile) because anything we broke would be less than the deductible," said Aultman, who never had been on a snowmobile. "So Brett and I went to the top of the mountain, and we took off to see how fast we could go. Brett told me to be careful because there was a large ditch (a ravine) that was clearly marked.

"I floored it and I looked back to see Brett standing and waving. Next thing I know the bottom had fallen out of the world. I was flying through the air, so I jumped off."

Aultman's body was driven into a snowbank and the snowmobile was destroyed when it hit the ground.

Raymaker rushed to the edge of the ravine, yelling "Taylor."

"I could hear Brett yelling my name, so I knew I wasn't dead," Aultman said.

"His sled went into the rocks," said Raymaker, who saw that Aultman wasn't seriously hurt. "His helmet had turned 90 degrees. He was looking out his ear hole."

The story is now a moment of Willis Smith lore, and it's something that everyone laughs about in an all's-well-that-ends-well kind of way. But the magic came after the accident.

"There were 14 of us (in Breckenridge) and we all offered to pay for the snowmobile," said Sessions, who said all his company's future snowmobilers took out the insurance. "It tells you what a trip does — it creates bonding. You get much closer."

Aultman turned down the $7,000 it cost for the snowmobile because, "I did it," but he noted, "Everyone looks out for everybody."

Sessions started to make sure "everyone looks out for everybody" when he joined the company in 1988, after his previous job dried up when E.E. Simmons Construction of Sarasota went out of business.

"I started at E.E. Simmons as an assistant project manager and went to project manager," Sessions said. "I knew that Leighton Hunter (the Willis Smith CEO) was planning on retiring. He was looking for someone who could take over the company. I was 28."

Willis Smith Construction had nine employees in 1988 and it seemed like the perfect spot for Sessions, who had come out of the University of Florida with the goal of owning his own business.

However, Hunter wanted to make sure Sessions had the right goals and work ethic. So he took about a year to look him over before cutting him a deal.

"At the University of Florida, they used to have guest speakers who were owners of construction companies," Sessions said. "I would listen to their stories. But I didn't know anything about what it took to run a company."

He had mortgaged everything he had to buy into the company and on Jan. 1, 1989, he was a co-owner.

"The reality hit him that I had made all these commitments and there was a great burden I didn't think about," he said. "Oh my gosh! I have all these employees, and they all are depending on me. I had better be successful."

Fortunately for Sessions, the small company had a great reputation. he said founder Willis Smith and then Hunter were known for their integrity.

But in 1988, Willis Smith Construction did $2.8 million in revenue.

'The company couldn't justify paying me," Sessions said. "Leighton told me not to worry about it."

Hunter had confidence things would take off with Sessions in charge, and it did, doing $6 million revenue the next year. Sessions hired some of his former coworkers from E.E. Simmons as they gained projects.

"The challenge was getting in front of more clients and architects," Sessions said.

The company began to diversify into the religious market along with schools. Sessions said once they did a job, they differentiated themselves from the competitors by not "nickel and diming anyone" and by not looking for excuses.

"I tried to put myself across the table in my clients' seats," Sessions said. "We created an environment where people wanted to work with us. Leighton Hunter always was client oriented and we continued that. I had the same values as he did and I learned from him. Running a business is about how to treat people fairly. Our philosophies were incredibly aligned — hire bright, intelligent people and in the first few years, build character, ethics and integrity. We started doing that in 1996 with (project manager) Wade Wolfe."

That same year LaCivita, who in 2004 became a co-owner and now is company president, joined Willis Smith Construction.

"When I first started, it was 'Here is your office, go find a job,'" LaCivita said. "They gave me enough rope to hang myself, but I was doing what I loved and the people were like a family. I saw this as a life career job. I couldn't get it better anywhere else."

The message was the same for the Aultman, Carr, Otterness and Raymaker when they joined the company in the early 2000s. Sessions told them to learn from their mistakes.

"You get hard lessons and each one is a blow," Sessions said. "But if you don't learn from them, shame on you."

All the executives were the result of long term planning as Sessions knew he had to maintain his leaders in the long term. He made it possible for all of them to become partners.

"I came to Willis Smith with the intention of starting my own company," Aultman said. "At the time, it was a small company. But I loved coming to work and Dave and John gave us the chance to succeed, and fail. I always felt that this was my company, and now it can be."

Raymaker started working for Willis Smith in August 2003 and was assigned to The Ringling's Visitors Pavilion, which when constructed would include a space for the Historic Asolo Theater. Preserving the theater was part of The Ringling Master Plan of 2000 to save the 18th century artifact but to include 21st century auditorium seating and ambient lighting.

"It was baptism by fire," said Raymaker, who said his first project was the project of a lifetime.

LaCivita didn't shield Raymaker from pressure.

"John had a lot of trust in us," Raymaker said. "I was 24 and in 2005 and 2006, we had huge supply issues. Steel, concrete, metal framing. It was an interesting market and we had price increases. John tasked me to talk to Florida State (the owner) about the cost overruns. It instills confidence in you. We had the authority to run a job the way we wanted to run it."

Raymaker said he spent his first four years with Willis Smith working alongside Otterness out of a trailer next to the Visitors Pavilion. It was a climate for bonding.

"That was where we grew up," said Aultman, who started in 2004 and also worked out of that trailer. "It was just like you would expect from 20-something UF grads who were all single. It was a frat house. But it bonded us all together.

"Brett was the best man at my wedding. When you go to work with your best friends, it's fun. It makes you want to come back."

Liz Brookins, a three decades employee who started as a receptionist and is now the senior marketing coordinator, has watched the family atmosphere develop over the years at Willis Smith.

"I had been in construction previously and I had a low opinion of contractors," Brookins said. "I was told these guys were different, that all subs always would be paid. That was Smitty's (Willis Smith's) philosophy."

She has watched the executives bond.

"They grew up together here," she said. "I remember they were fresh out of college. I watched them become polished professionals. I watched them get married, have kids."

The Willis Smith headquarters moved to Lakewood Ranch in 2008 from the Hyde Park office off Tuttle Avenue.

So what has made the company so successful?

"Integrity," Brookins said. "When the sub contractors always want to work for you, there is not a better compliment."

With 85 employees now, Willis Smith did $101 million in revenue in 2021.

Despite expansion, it remains a family environment. When projects approach deadline and an all-hands-on-deck effort is needed, everyone might be summoned to a job site to push a broom and clean windows.

"You become family," LaCivita said.

Sometimes being part of a family means going to a concert, even if it's not a fun prospect. LaCivita said Sessions is a fan of the rock band "Tool."

"Here is this soft-spoken, introverted, numbers person," LaCivita said of Sessions. "I hated it. My hearing is permanently damaged."

Sessions said he has enjoyed rock music since he was a teenager.

"I didn't want to drive to Ft. Lauderdale by myself," he said of taking LaCivita to the concert. "Hey, it's bonding."

It's also fun. Sessions always thought a fun environment would keep his employees around. Aultman said the only question at his first interview with Sessions in 2003 was, "Do you like to drink beer?"

Raymaker wore a jacket and tie to his first interview with Sessions and LaCivita. Sessions wore shorts and LaCivita had a bathing suit on. Both were wearing flip flops.

Carr was an hour late for his first interview but he said everyone was so busy no one noticed.

It was the face-to-face interaction that was most important for Sessions and LaCivita and eventually the other shareholders.

"I hate emails," LaCivita said. "You've got to have people skills in this business."

"If somebody doesn't pick up the phone, you go find them," Raymaker said. "That's a lost art."

Carr said it isn't a lost art at Willis Smith.

"If something is becoming a problem, you do it in person," he said.

So even if Sessions believes the people are what makes Willis Smith the company it has become, what is his favorite project?

"The bigger thing is the body of work," he said. "It's not about an individual project. It's more about how we start a relationship. Our first project with Mote Marine was 1991, and we've been with them 31 years. We've built just about everything for them. The Ringling was 1992, and at first it was a small project. We've been 30 years on that campus. We work with the school districts in Sarasota and Manatee counties. The schools are a reflection of who we are."

Did Sessions ever expect Willis Smith Construction to be building a project like the Mote aquarium when he first arrived on the job?

"I thought it would have required a company with a greater level of sophistication," he said. "International builders. "But in the early 2000s, we completed that project at The Ringling. We had competed against nationally prominent construction managers who were 50 times our size at the time. We had the reputation to get in front of the right people.

"All through the 2000s, John and I didn't take anything out of this company. Everything we earned went back into it. We wanted financially, structurally to have the sophistication and management to be able to do anything in the Sarasota region. I wanted that work to stay local."