- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

The material has been marinating for 1,000 years. You know it even if you don’t know it.

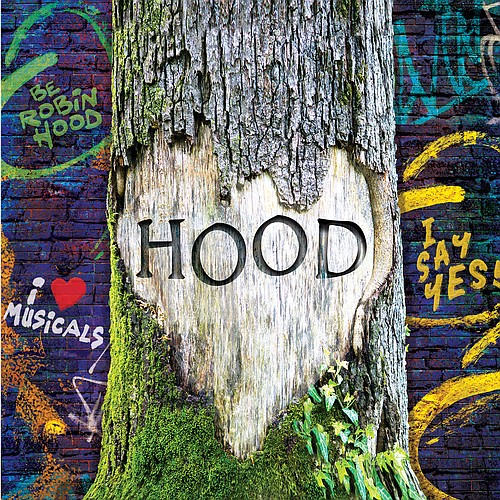

And that’s where the challenge comes in for the creative team behind "Hood." Douglas Carter Beane, the playwright behind the Asolo Repertory Theatre production, attempts to bring the story of Robin Hood into the current day.

His husband, Lewis Flinn, has the task of writing original songs that will only burnish the existing legend. "Hood" last saw the stage in Dallas in 2017, but it’s been tweaked a bit in the intervening years. The script is a living and evolving creature, says Beane, who recently joined Flinn and the Observer on a call to discuss the upcoming production.

“If you're really good at what you do, it can be timely and it can be timeless at the same time,” says Beane, a five-time Tony Award nominee who successfully re-created "Cinderella." “The stories we're basing this show on have been around since the 1100s. They were ballads; there was no one author; there are several different people who would make up these stories. I would say, except for one through-line of our show, every one of them was one of those original stories.”

"Hood" has had a long gestational cycle, first created at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. It had iterations at the Royal Academy of Music in London and at a Shakespeare Festival in Scranton, Pennsylvania, before having its run at the Dallas Theater Center. But then came a turbulent political time in the U.S. And then came COVID-19.

Inevitably, some of the play had to change. Beane says that before the pandemic, the play might have come to the stage pretty much the same way it had been written. But Flinn was able to use the time between productions to make the play more musical, to add flourishes that just weren’t possible the first time around.

“When we were writing at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, it's not a musical program,” says Flinn. “So none of the actors were singers at all. None wanted to be. None pretended to be. The challenge was to write songs that non-singers could sing and still sound good. Even though it's since gone on to professional productions and I’ve put a lot of arrangements into it, it has a score that is, in my mind, sort of for the everyman singalong.”

Flinn allows that there are no “Sondheimian intervals” in the music, but he says the songs have influences ranging from Celtic sources to Kurt Weill, folk rock and soul.

And that’s part of the charm of the material, Beane says: It can adapt itself to a number of tones.

Beane says he was encouraged to write "Hood" after reading bedtime stories to his children; they loved the tales of Robin Hood, even though they were 1,000 years removed from the times they were created.

That’s because the stories have an elemental structure to them that people instinctively appreciate.

“They are first and foremost stories of of a hero. But they have a lightness and humor to them that I respond to,” says Beane. “A friend of mine who's a writer said, ‘Robin Hood is always laughing. When you think of Robin, he’s always standing on a log and laughing.' I said, ‘Yeah, he's a fun guy.’ That image was obviously an influence.

"But the stories are fun stories. And somehow, they're in our brains, even if we don't remember ever seeing them.”

Beane mentions the Errol Flynn and animated Disney versions of Robin Hood that have become ubiquitous in pop culture, and he says there are moments in the legend we all recognize instinctually.

There’s Robin donning a disguise to enter an archery competition. And there’s the moment Robin meets Little John on a bridge for the first time, among others. The art comes in taking those moments and still saying something original.

Beane and Flinn first met while working on "Music From a Sparkling Planet," which was directed by "Hood" Director Mark Brokaw and had its theatrical run in 2002.

“I would say that actually we met as collaborators,” says Beane. “I had written a play. Mark Brokaw was directing that play. And he hired Lewis Flinn to bring music into the play. I initially was very upset because I had selected some bound music for the show. But when I heard Lewis's music, I remember I started to cry because I thought it was so beautiful.”

“It’s been 20 years of tears ever since,” jokes Flinn.

The pair have both collaborated with Brokaw several times; Brokaw, for instance, directed Beane’s wildly successful adaptation of “Cinderella.” Together, Beane and Flinn have created "Lysistrata Jones," and Flinn contributed music to Beane’s “The Little Dog Laughed.”

They’ve also worked together on things that haven’t yet seen the light of day.

“We have an easy rapport. We get along,” says Beane. “We have very similar tastes in theater. Rarely do we leave a show that we didn’t write, and he says, ‘Oh, I loved that,' and I say, ‘Oh, I hated it.’ Usually, we have a very similar aesthetic. We like a lot of the same music. Louis is a lot more high-brow than I am, but it’s an easy collaboration.”

How do they work together? Are you picturing the married playwright and lyricist sitting side by side at a keyboard and carrying out their tasks? That’s not really the way it works.

“We don't sit in the same room, creatively,” says Flinn. “We do when we want to review or discuss something. But a lot of time, it's separate. And you have to be careful; I'll be working, but Doug may have moved on to a different project. I'll be on this and want to bring it up, so I just have to say, ‘OK, I need to schedule a time to discuss this tomorrow at 11 a.m.’”

“I'll be working on something else or maybe watching television,” says Beane, adding that Flinn generally works in a studio across from their apartment. “Then a little bling will show up on my phone, and he'll send me an email on the draft of a song. And that's always like a nice little bonus treat. If I'm in a restaurant, I get to just run into a bathroom and play it.”

The pair has been working on this play since the Obama administration, but they've taken time out in that span to work on other projects. Beane singled out one cast member, Billie Aken-Tyers, who has been a part of the project since the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.

Aken-Tyers began as an assistant director on "Hood," and when an actor got sick, she stepped in and played the role. Now she’s a permanent member of the cast. Beane and Flinn say that the cast of "Hood" is an instant community, a family that has worked to bring the story to life over a number of years.

The show has evolved with the times they live in, but at root, it’s still a story that has thrilled people for 1,000 years. Neither Beane nor Flinn wants to get ahead of themselves and predict what happens to "Hood" after Sarasota.

"Honestly, we're not thinking beyond this opening," says Beane. "The minute you start putting stars in your eyes like, 'This will go into the Majestic Theatre and kick out "Phantom of the Opera,"' you're dead because then you're not doing the work."