- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

For years, the music lived inside James Grant’s head, and it had no outlet in the world.

But now it’s about to be set free.

Grant’s grand vision, a symphonic choral cantata entitled “Listen to the Earth,” was originally commissioned to serve as a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Earth Day.

It got delayed and postponed twice due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it will be played Sunday for the first time at the Sarasota Opera House. It will take a chamber orchestra and two choruses to pull it off, and the composer, in the audience, imagines his reaction when the time comes.

“When I’m sitting in the Sarasota Opera House getting ready to hear the piece, the overwhelming feeling I’m going to have is one of gratitude and humility,” says Grant. “That’s how I’ve always felt as a composer. I get to do this. I get to create scribblings on paper that end up meaning something to people, and talented people transfer it to their instrument and music comes out.

"There’s just something quite miraculous about all of that.”

It’s even more miraculous when you consider the timeline and the immense scope of the intended project. Grant first began talking about the cantata with Choral Artists of Sarasota Artistic Director Joseph Holt about six years ago, and they hoped to take humanity on a ride to explore our commonalities.

Famed speakers including Jane Alexander and Terry Root had been enlisted to speak, and the event was supposed to include film screenings and panel discussions about the world and what human beings can do to be better stewards of the environment.

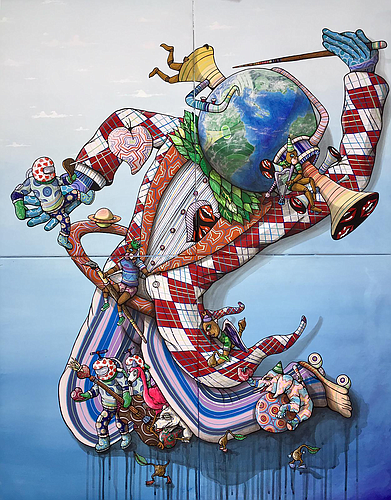

There was also an artwork commissioned with the same name — "Listen to the Earth" — painted by Francesco Baronti that will be on display during the Sunday performance and available for purchase via auction after it.

Although some of the context has been lost due to the pandemic and circumstances beyond the composer’s control, the heart of the project remains. And that’s the composition, which takes the shape of an astronaut’s journey deeper into the solar system.

The perspective of the astronaut will be played by baritone soloist Marcus DeLoach, and the chorus will serve as the voices of Mission Control guiding the audience through the piece. In some places, the chorus will be singing actual words from actual Mission Control transcripts; Grant says they were available because they were public domain.

"I never ever thought I’d set the word trans-lunar injection for music," he jokes.

For a while, he says, he wasn't sure how to tell such a timeless and universal story. He didn't know how he could encourage humanity to value taking care of itself and its immediate environment. But over time his task came into focus.

Grant became obsessed not just with Earth Day, but with the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, which was commemorated in July 2019. And he found himself reading the accounts of not just astronauts on this journey, but on several journeys thereafter. All of them, said Grant, began to express the same exact feelings.

They’re moved by the experience of escaping gravity for the first time, and they describe the image of the Earth in space as a tiny blue dot in a sea of planets and stars and celestial bodies. But how do you describe that musically?

Grant, who splits his time between Sarasota and Oxtongue Lake, Ontario, says he just gets out of the way.

“Writing music is like writing fiction,” says Grant. “There’s suddenly a knock at the door and you don’t know who the hell it is. It’s the same thing with composing. One of the fascinating experiences I had with this piece particularly was when it began to take shape. As I began to put the pieces together, it began to inform me where the storyline needed to go. I’ve never had anything close to writer’s block. I don’t get in the way of the creative impulse. I feel that writer’s block is a matter of the ego of the artist wanting the creative impulse to go in a certain direction that the creative impulse didn’t want to go in. You have to listen to that and follow it.”

Grant describes the act of composing as micromanaging the experience of time with sound. He wants to take you on a journey into the cosmos with nothing to propel you except voices and instrumentation, and every second forms a vital part of that soundscape.

And in this case, he had years to scheme out how those seconds should sound. Grant says that the piece was nearly finished in March 2020 when he got word it wouldn’t play as scheduled. So he moved away from it for a while. Then he heard of the second postponement last April, so he didn’t really dive back into completing it until October 2021.

By this point, says Grant, he’s a different person doing the composing. The piece is different and the world is different, and the new perspective helped inform its final state.

“I dove back in and found myself so thoroughly absorbed by the intricacies,” he says. “You think of all the moving parts that had to fall into place for this extraordinary event to take place. Just the mechanics of all of it. I got really caught up with the orchestrations; I found myself adding so much detail in little tweaks that really make the music pop.

"The piece had some time to age and mature, and there’s an overall depth to the artistic impression that has expanded.”

That added depth gives the orchestra and the Choral Artists more signatures to grab onto in their expressions and articulations. Grant says that he’s known Holt for decades and considers him to be one of the finest musicians he’s worked with, and they have a prior experience of premiering a Grant composition inspired by Walt Whitman at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

The Women’s Ensemble of Parrish Community High School will be adding their voices; the program will also include another piece by Grant, “Earth — Poem of Thanks to our Common Home,” as well as “The Lark Ascending” by Ralph Vaughan Williams performed by Sarasota Orchestra concertmaster Daniel Jordan.

But the centerpiece of the evening is the world premiere of “Listen to the Earth,” and the man standing in for all of humanity will be baritone soloist Marcus DeLoach.

“Marcus has worked with us before over the past decade,” says Holt. “He has a way of delineating text, and as a singer that’s really important, especially with something new that people haven’t heard before. He’s the perfect person to portray this astronaut character.

“At one point we actually sent Marcus a picture of an astronaut outfit. We said, ‘This is what you’re going to wear in the performance.’ And I think he thought we were serious.”

Holt said that he is thrilled that he finally can present “Listen to the Earth” to the world, but he does fret a little about the lost context of the events that originally were slated to surround it. Holt says that he and Grant had hoped to raise consciousness about the fragility of the planet, and now the art will have to spread the message by itself without its intended support.

“The audience I think is going to be in for a wonderful surprise,” says Holt. “Jim’s music is very dramatic, but it’s also very approachable. There are certain types of 21st century composers that are blips and bleeps or some type of minimalism where they just repeat the same chords over and over. But this has a lot of color to it.

"There’s just an incredible expressive quality he’s able to capture. We’re working in it and living in it right now. We’re pretty excited about it, but an audience is only going to hear it once, which presents its own unique challenge.”

Grant, for his part, says that the hard work for a composer comes in finding a new life for his compositions. He says this orchestration of "Listen to the Earth" is built for a chamber orchestra, but that he’d like to build it out for a larger body of musicians to play.

The composer says he does not think of legacy and he doesn’t think of posterity; he doesn’t really consider the possibility that the work could be played long after he’s gone, but he knows how much work it will be just to make sure it’s played again while he’s here.

“Having music performed on this level by such extraordinary musicians is a privilege,” he says. “It’s really up to the composer to ascertain whether the piece can have an afterlife.

“If the answer is yes, that’s when we put down the composing quill and start marketing the bejesus out of the piece to other conductors. I’ve already talked to a number of conductors who are very interested in the piece. What I’ve always understood is that if conductors hear a fantastic piece, just because they love it doesn’t mean they’re going to program it.”