- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

A few weeks ago, the Longboat Observer argued that local governments’ annual budget books are a disservice to taxpayers. The editorial pointed out that budget documents provide hundreds of pages of detail but little in the way of useful information for citizens to understand what their tax dollars are doing.

Civic and elected leaders love to talk about wanting citizens to be more engaged in local governance. But when you can’t figure out which government services have been provided and in what quantities and are unable to determine such information from government documents, there is not much incentive to get involved.

Years ago, I created and managed a project that gave awards to cities and counties that produced outstanding “citizens’ budgets,” clearly identifying where revenue goes and what it provides to taxpayers, linking government expenditures to outcomes that taxpayers can observe.

For example, the breakdown listed how much it cost to fix each pothole and how much was being spent for each visitor to the library. Such metrics truly inform taxpayers in understandable and transparent ways.

To improve the relationship between the governed and the governing, governments need to focus on better performance, more efficient government and a better informed citizenry. Citizens want to know how effectively and efficiently their city delivers services.

To properly serve their citizens, governments need to provide data that gives policymakers and citizens a full understanding of the array of results possible through different levels of spending.

For example, citizens want to know what resources it takes to pick up the trash, fix the streets and provide fire protection. They want to know how their city stacks up against neighboring or similarly situated cities.

Do some cities use more or fewer resources than others? Are there other management options that officials can use, such as intergovernmental agreements or public-private partnerships?

The idea here is to shift focus in both management of local government and budget planning and reporting away from inputs and toward performance. When management measures performance — what taxpayers want to know — it measures success. You know the saying: What gets measured gets done.

More important, though, measuring performance allows policymakers to distinguish policy successes from policy failures.

If local state and local government jurisdictions really wanted to be transparent and provide useful information, their annual budget documents should include all of the elements we list in the accompanying box.

Think what this would mean for the budgeting process. For starters, local elected officials could expect their agency heads to present a budget request with actual data on how the money has been used in previous years, what they have accomplished with it; and what they would accomplish with additional funding.

Instead of vague conversations about growth and the need for ever more funding, these hearings would be tied to the relationship between dollars and performance. For citizens, this would mean focused discussions on efficiency and whether citizens are getting what they pay for.

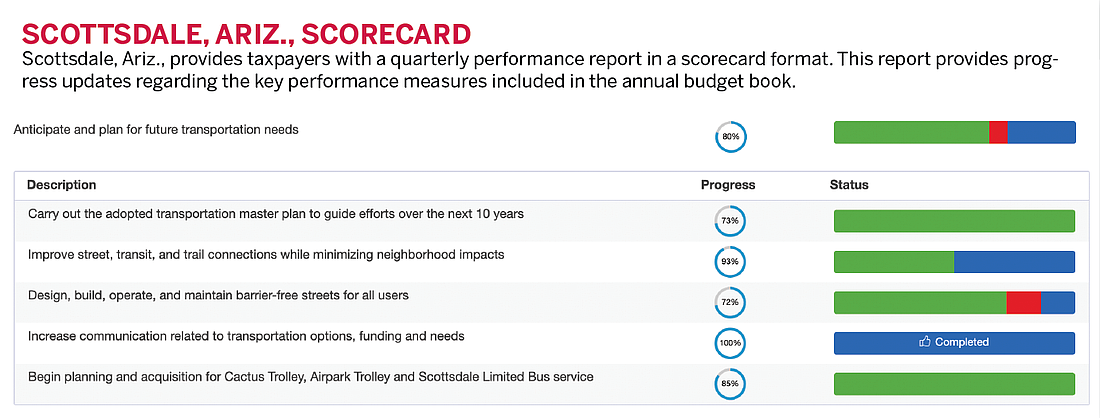

Everyone involved would be required to do a lot of work for budgets to be this way, but technology is making the job easier every day. Amazing tools are now available to present data and budget spreadsheets in clear visual formats. I have included an image from the city of Scottsdale, Ariz., to show what can be done.

A budget like this would foster better management by local government and better decision-making by local elected officials.

And it would improve the ability of the media, citizens and watchdog groups to understand the budget and engage with budget decisions on a much more fundamental level and in a way much more worthwhile.

This would certainly mean a lot more citizen engagement.

Adrian Moore is the vice president of Reason Foundation and lives in Sarasota.