- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

To some people, “The Nutcracker” is like the fruitcake of holiday entertainment — so ubiquitous as to be blasé. But just like fruitcake, when you get a really good one, you realize why it’s a tradition.

In 2012, the Sarasota Ballet reimagined the Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky classic with its “John Ringling’s Circus Nutcracker,” a brilliant blending of the original fantasy-filled tale with local big top lore and art deco elegance.

It’s hard to say when something can be considered a tradition, but if this production isn’t there already, it’s well on its way. It will take another step in that direction when The Sarasota Ballet, teaming with the Sarasota Orchestra, presents its fifth edition of “John Ringling’s Circus Nutcracker” on Dec. 20 and 21.

For those who might not be familiar with the production, it is essentially the traditional Nutcracker story, only set in 1930s New York, where a young girl and her family meet up with John and Mable Ringling and members of their circus. Later, the girl enters a fantasy world populated by the Ringlings, as well as clowns, exotic animals and circus performers.

Choreographer and librettist Matthew Hart’s clever fusion, given form by designer Peter Docherty and brought to life by the performers, is a carefully crafted world.

The following series of photos dives into the story of the unique ballet, while sharing some lesser known facts about its production.

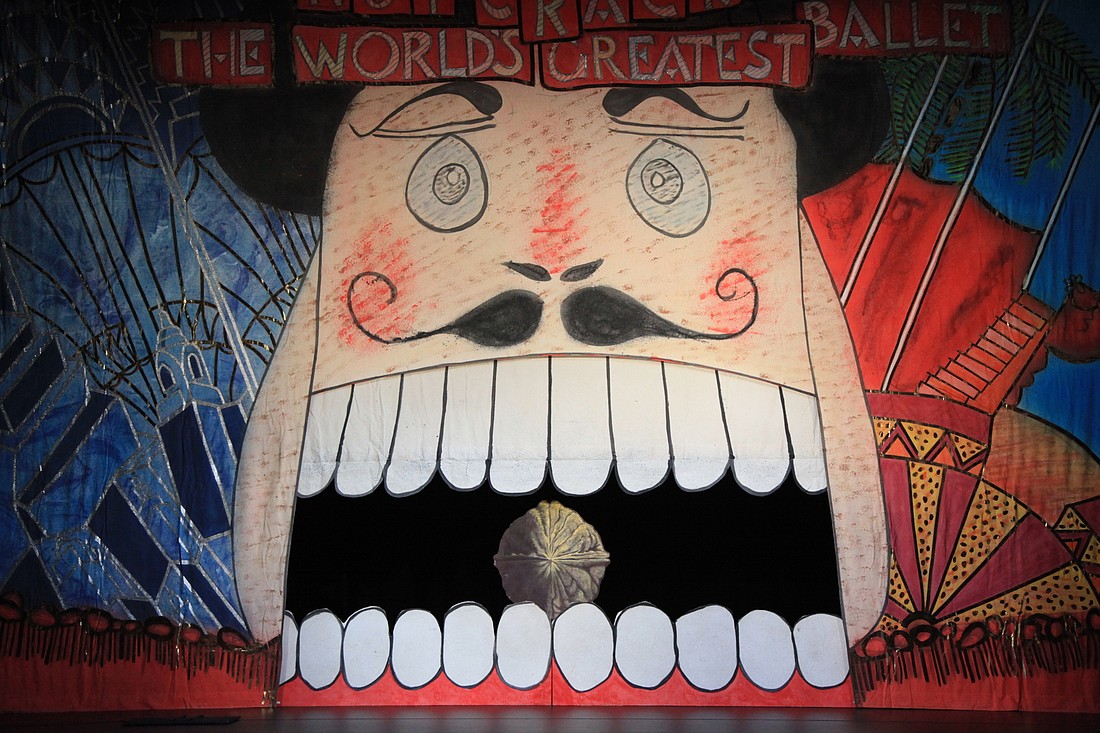

For starters, both acts open with a giant nutcracker head doing what nutcrackers do best. As with every effect in the show, the immense teeth are raised and lowered manually, requiring perfect timing by the stage crew.

The Nutcracker/Ringling/1930s motif is established immediately when our young heroine, Clara, and her family meet Ringling Circus trapeze stars Sugar and Prince, as well as circus king John Ringling, at Grand Central Station.

Later, at a Christmas Eve party, John Ringling gives presents for the children: a ringmaster nutcracker for Clara and a large windup mouse for her brother, Fritz, which he uses to torment his sister with great precision. The mouse is built over a remote-controlled car, discreetly controlled by one of the clowns in the cast.

That night, the nutcracker and the mouse come to life and do battle as Clara and John Ringling look on. In each performance, the cast includes 25 children from Sarasota Ballet School and Dance – The Next Generation, many of whom make up the clown and mouse armies.

Once the battle is over, John Ringling’s late wife Mable Ringling descends on a crescent moon as the Christmas Fairy, to revive the Nutcracker. That moon is the most difficult technical feature of the show. In Act Two, when John and Mable fly off together, it takes five to seven stagehands to operate it.

Act One closes with Clara running off with John Ringling North to a fantasy world — or in this version, Sarasota, to join the circus— seen off with the traditional “Waltz of the Snowflakes.” But, being in 1930s New York, if you look closely, these snowflakes’ costumes and headdresses take their inspiration from The Chrysler Building, and their choreography is inspired in part by the Radio City Rockettes.

The initial inspiration for creating a Ringling-themed “Nutcracker” was the resemblance between a traditional nutcracker and a ringmaster. In many traditional renderings of the ballet, the character Drosselmeyer’s nephew is turned into the Nutcracker. For this production, making the Nutcracker character John Ringling’s nephew and successor John Ringling North seemed a perfect parallel.

Much of Act Two consists of dances based on circus acts. Interestingly, as the dancers are onstage playing acrobats, aerialists, clowns and even exotic animals, a significant portion of this production’s backstage crew are current and former circus performers.

Nearly all of the choreography For “John Ringling’s Circus Nutcracker” is original, the exception being Act Two’s famous pas de deux, virtually unchanged from the traditional “Nutcracker.”

Another easy melding of fantasy and reality occurs late in the second act, when the “Waltz of the Flowers” becomes “The Waltz of the Roses,” the entire scene a reference to Mable Ringling’s famous rose garden.

In Act One, when John Ringling is handing out toys, a figure of his beloved Mable is placed at the top of the Christmas tree. In a touching finish, after John and Mable fly off on the moon, Clara wakens, wondering if it was all just a dream. Atop the tree, a figure of John has appeared at Mable’s side.

Trying something new is always a risk. Back in 1892, “The Nutcracker” was initially a flop; considered a little too different for 19th-century Russian audiences.

“John Ringling’s Circus Nutcracker” has fared much better. It’s a production that can captivate even the most Nutcracker-weary, reminding us of its importance as a holiday tradition.

For so many of us, going to see “The Nutcracker” is our first exposure to ballet or symphonic music. In a culture that increasingly glorifies unrefined tastes, it’s important for young people to see for themselves that there’s more to ballet than men in tights and women in tutus doing pliés and pirouettes. That first exposure is important, and it’s important that it’s a memorable one.