- April 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

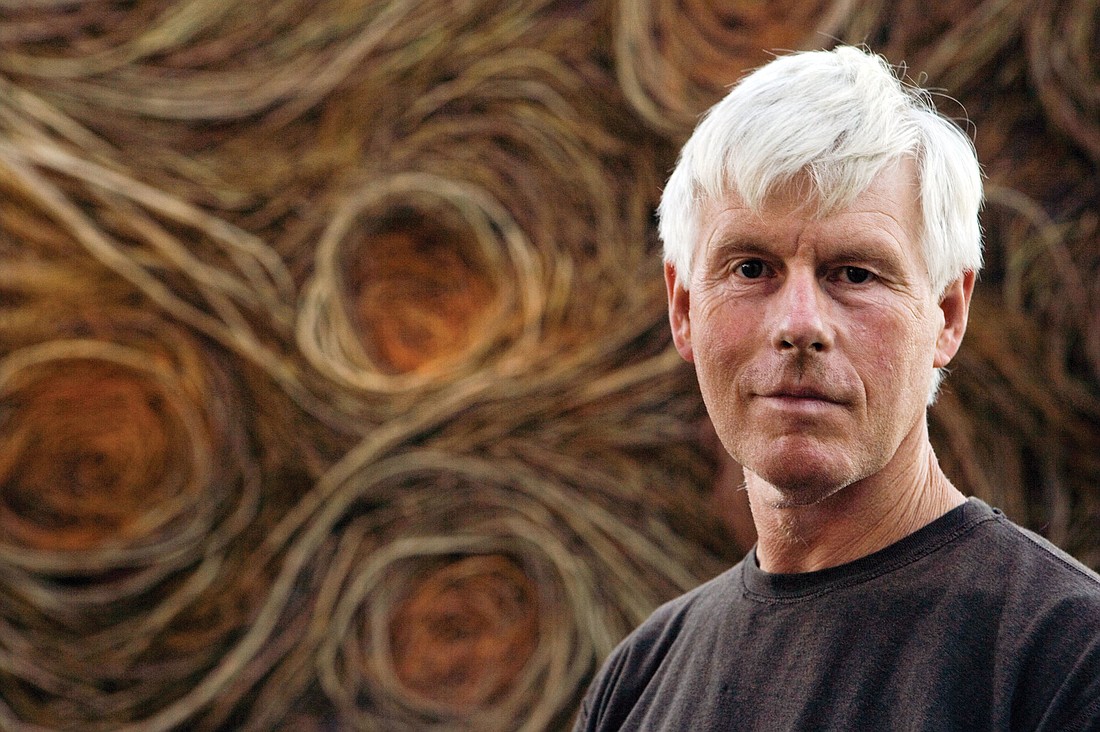

Sculptor Patrick Dougherty’s art began as a child in Southern Pines, N.C., in a dell surrounded by dogwoods and pines near his home — a place he describes as “a home away from home.”

Being the eldest of five children, Dougherty instructed his siblings to collect twigs, sticks and vines for him. Then he wove them into elaborate hideouts and tree houses where he and his siblings played and let their imaginations run wild.

Today, his art installations, one of which will be coming to the grounds of Sarasota Museum of Art/SMOA, a division of Ringling College of Art and Design, starting Jan. 7, stem from the same pattern of weaving natural materials and use the same childlike imagination with which he built when he was young.

But Dougherty didn’t honor his childhood artistic roots until later in life.

Instead, as an adult, he opted to study health-care administration and serve at an Air Force hospital in Germany during Vietnam.

“Then I kind of went through my hippie era and got back to the land,” he says in a phone interview. “I had my eye on becoming a sculptor.”

The 67-year-old went back to school for art in the early ’80s, at the University of North Carolina. He had no formal knowledge about sculpting — but he hoped to make ceramics.

Then, a project, a woven-sapling, nest-like sculpture, took him back to his childhood. It may have been easy and natural to him but the artwork wowed his professors.

“Once a person aligns a basic instinct with their hands, (it results in) something that is beguilingly easy,” he says.

Dougherty has never studied primitive indigenous cultures, although his work looks like a cross between an earthy living structure and a bird’s nest. It all boils down to his natural instinct.

“I believe you contain the same information inside you (as birds and primitive people),” he says. “Birds have the same problems I do, and I have the same problems indigenous people had, so (our) work can look the same.”

According to Dougherty, everyone contains the shadow life of our hunting and gathering past, especially children who unknowingly play it out.

“You don’t have to tell a kid about a stick,” he says. “They immediately assess the potential and use it as an imaginative object.”

At least, that’s the type of child Dougherty was.

“I’ve looked into that place as an adult, and some of the imagery and the fantasy must be coming from the distant past to some degree. And I think that bleeds over into the way the audience appreciates and accommodates themselves to the objects,” he says.

He hears a variety of reactions from people throughout the two to three weeks he spends on-site building his structures.

“People talk about the forts they’ve built, the bird nests they’ve seen or the indigenous people they’ve visited,” he says.

Aside from the youthful nostalgia triggered from seeing his work, the natural materials bring light to environmental topics, as well — especially to the volunteers helping with the project.

“I think everyone has a common feeling that they are part of systems they can’t change, and (they have) a general awareness of what relationship we have with the natural world and other animals,” he says.

Dougherty believes his childhood connection with the earth is much different than today’s children have — not many have the chance to grow up planting on their grandfather’s farm.

But not everything in life stays consistent through the years; even Dougherty’s sculptures are temporary. The 239 sculptures he has made around the world throughout his career have eventually returned back to the earth from which they came.

“It’s a concept that art should outlast us all and inform the future, but, in fact, our historians should carry that burden, not artists per se,” he says.

There’s a certain practicality to the limited viewing time of sculptures, because there’s no upkeep.

“There are great contemporary places to make a sculpture. And if a piece can bond with a site and ultimately come down, then something else could happen there,” he says.