- February 4, 2026

-

-

Loading

Loading

Navigating New Pass by boat is no simple task.

“You literally have to follow a zig zag following where it’s deep,” said Jane Early, marina manager of MarineMax, which stores hundreds of boats at its New Pass-bordering marina and dealership. “You have to hug the left side, then go to the right side, and then there’s a new sandbar and you have to go around that one. It’s not an easy way.”

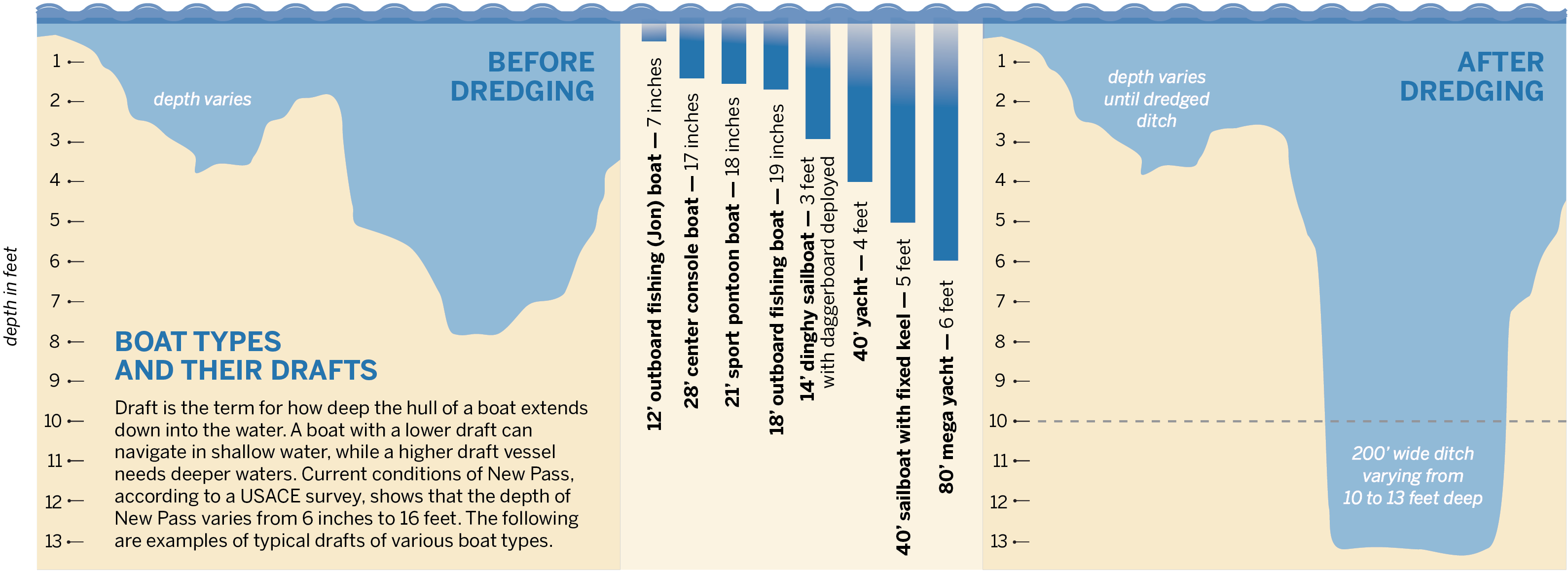

According to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration charts and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredging plans, the depth of New Pass varies from 6 inches to 16 feet. And with the sea floor shifting from storm to storm, weaving through the pass is done so at boaters’ risk.

Early said she advises those embarking into the Gulf from MarineMax to take the long way, either southeast under the Ringling Causeway and out Big Sarasota Pass or northwest past the 11-mile barrier island of Longboat Key and out through Longboat Pass.

But a dredging project underway on the channel connecting Lido Key to Longboat Key’s southern end will create a path that could clear the way for larger vessels.

Phillip White, superintendent of Gator Dredging, said his company was contracted to dig a 180-foot-wide ditch at the bottom of New Pass.

“The contractor is using a hydraulic cutter-suction dredge, which excavates shoaled material from the bottom of the channel, blends it with water to create a slurry, and pushes it through a pipeline to Lido beach, where it is being deposited within the permitted Lido Key shore protection project footprint,” said USACE spokesperson Peggy Bebb in an email.

The depth of the cut will be 10 feet east of the drawbridge and 13 feet west going out into the Gulf. The sand collected in the dredge is being piped to south Lido Key Beach for a renourishment project, but another result of the project will be enhancing the navigability of New Pass.

“The reason we’re pulling the sand up is because it’s a navigational hazard right now. Everybody runs aground there,” White said. “That’s what the Army Corps of Engineer’s got permits to do. That’s why we’re doing it. We get paid to do the depth as required, but they reuse the sand to refurbish the beach while we’re here. It’s a multipurpose thing. Tourists get their beach. Locals get their depth and get a nice, clean channel.”

The dredging and renourishment project is being led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. According to a USACE spokesperson, the project has two objectives: maintaining the New Pass channel via dredging and restoring Lido Key shoreline protection through renourishment.

At the Sarasota Sailing Squadron on City Island, sails are typically pointed so the wind takes sailors away from New Pass and into Sarasota Bay where depths are more predictable. General Manager Susan Clark said she only knows a handful of sailors who even attempt to go out to the Gulf, and when they do, they go under the Ringling Causeway, around Bird Key and through Big Sarasota Pass.

Even though sailboats stored at the Sailing Squadron don’t typically have hulls with deep drafts, some with keels require more depth than others.

“Most of the sailing that we do, we stay out of the channels and we’re just in the bay,” said Nick Lovisa, sailing director of Sarasota Youth Sailing. “But some of the bigger keel boats have a harder time getting out there, and they have to follow the channel.”

David Miller, who has lived on Longboat and boated in the waters around it for more than seven decades, said New Pass hasn’t been a reliable way into the Gulf since the channel markers were removed in 2017.

Those markers gave boaters a level of trust to navigate a channel.

“Normally in the channels, they designate it between 8 to 12 feet, but if you’re outside the channel and it’s not marked, you’re at your own risk basically,” Early said.

Without markers, it’s more perilous to navigate through a pass, even for boaters with extensive local knowledge.

“I’m not an authority, but New Pass has basically been closed to boat traffic,” Miller said.

Having navigation markers are key. Charts can be months or years out of date and radar equipment on boats often show the depth directly below the vessel, not ahead — not very helpful when you’ve already hit sand.

“They’re not the most accurate because you get bubbles on the transducer,” Early said. “It’ll go from 7 feet to 2 in like 10 seconds. Really, right now, it’s by sight.”

The good news is, after New Pass is dredged, the channel markers are making their long-awaited return.

“USACE and our contractor are coordinating directly with the US Coast Guard regarding proper placement of aids to navigation (ATONS) once the project is complete,” Bebb with USACE said.

But like a sandcastle on a beach, no dredge is permanent without maintenance.

“The New Pass inlet is a very dynamic environment with constantly shifting shoals,” Bebb said. “We encourage boaters to remain aware of Coast Guard Notices to Mariners and to stay up to date on the local knowledge.”

One example of that “local knowledge” is Miller’s observations of a sort of speed hump when crossing under the New Pass drawbridge.

“I know for a fact that right underneath the drawbridge, the center of what was the channel, is only about 5 feet deep, depending on the tide,” Miller said. “In low tide it’s even less.”

That five-or-so-foot bump will remain. White said his team will not dredge directly under the New Pass bridge because of an existing gas line.

For New Pass to remain a viable pathway for boats to travel after the dredging project is completed, maintenance is necessary. Bebb with USACE said “maintenance dredging of the entrance channel has been conducted every three to five years by the USACE,” and that the Coast Guard will maintain the navigation aids after the project.

But it just takes one storm to essentially reset the progress made by a dredge.

“They’ll be able to get into it for the first six months, but a major storm comes through here it’s going to close back off,” White said. “There’s so much sand out there to be moved.”

Jetties to reduce sediment movement is something local boaters would welcome on either end of the island. Miller, who more often uses Longboat Pass, points south to Venice, where twin jetties flank each end of the inlet.

“They rarely ever dredge that, but they’ve got those two great big jetties going out into the Gulf,” Miller said. “I think they function to the fact where they keep the pass open.”

Don’t bet on it on Longboat Key, though. There are no plans for anything of the sort, especially on the southern end, Public Works Director Charlie Mopps said, noting that jetties are expensive and difficult to permit because of potential impacts to surrounding coastal processes.

“If you try to put in a wide, long structure at an inlet to either hold the channel, jetty or a long wide groin in the vicinity of an inlet, you would have to prove that you were not negatively impact the natural movement of sand around the inlet to the downdrift beach,” Mopps said in an email. “So if the town tried to build something like that, the town through its construction of such a large long structure, would more than likely starve the city (Lido Beach) of naturally bypassing sand. No bueno.”