- April 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

When Chris Sachs lived in New Canaan, Connecticut, and rode the Metro North commuter train to and from his corporate executive job in Manhattan every weekday, he joined his town’s Kiwanis Club because, “it was just something you did,” he says. “Kiwanis was a big organization in New Canaan in the ’90s. It was made up of mostly young professionals and was as much of a networking thing as a service organization.”

Back then, he worked in the business side of the publishing industry. His crowning career achievement came in the late 1990s as the founding publisher of National Geographic Adventure magazine. Prior to that, he was the first advertising director for Men’s Journal, launched by Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner.

Now that Sachs is 66, retired and living with his wife, Tammy, in a spacious home on Longboat Key, his membership in the local Kiwanis Club represents something far different. Six months into his term as president, his involvement adds an extra sense of purpose to an already purposeful life. A lifeline if you will. “I never imagined myself sitting around with my toes in the sand,” he says, referring to his retirement, now 11 years in. “Sitting on the dock of the bay isn’t me. Kiwanis is a way to stay involved, to give back. I know that sounds kind of trite and old-fashioned, but it’s still true.”

Sachs joined the Kiwanis Club of Longboat Key shortly after moving to the island full time in 2017, sparked by Tammy’s chance encounter with former Town Commissioner Lynn Larson at a hair salon. The chapter was on the verge of folding due to lack of membership. Larson stepped in as president and corralled eight couples to save the club. Chris and Tammy Sachs were part of that core 16. From there, they were able to recruit enough folks to bring the roster into the 20s.

The Longboat Key Kiwanis’s primary beneficiary is the Children’s Guardian Fund, which provides emergency financial aid to kids in foster and state care. The club’s main fundraiser is the annual Lawn Party, which Larson says, “is probably the premier event on the island each year.” In addition, the Kiwanis coordinates the Salvation Army’s Red Kettle campaign at Publix during the holiday season. On any given day in December, you might see Sachs with a bell in his hand.

These are trying times for service and fraternal clubs like Kiwanis, Rotary, Knights of Columbus, Elks and such. Once a mainstay of American life, the organizations have not resonated with Gen Xers and millennials, and as a result, membership is dwindling. That’s especially true on Longboat Key, a haven for retirees and snowbirds with a population of 7,500 and a median age of 71. By Sach’s estimate, the club now includes four married couples, and the rest consists of single or widowed men. Its oldest member is closing in on 90.

Finding new recruits is tough. “People aren’t into service organizations like they used to be,” Larson says. “Even the older people are playing pickleball and the like. But Chris — ‘service’ should be his middle name.”

Sachs sees a silver lining amid the club’s membership struggles: Virtually everyone stays involved. “It’s a smaller group that seems to be doing more,” he says.

Kiwanis also provides the nexus of the Sachs’ social life outside of their extended family. And Sachs derives inspiration from his colleagues, regardless of their age. “I was immediately taken because they reminded me of the mentors that I had in my business life,” he explains. “They have the same sense of responsibility, duty, commitment, care, concern — you know, like-minded individuals.”

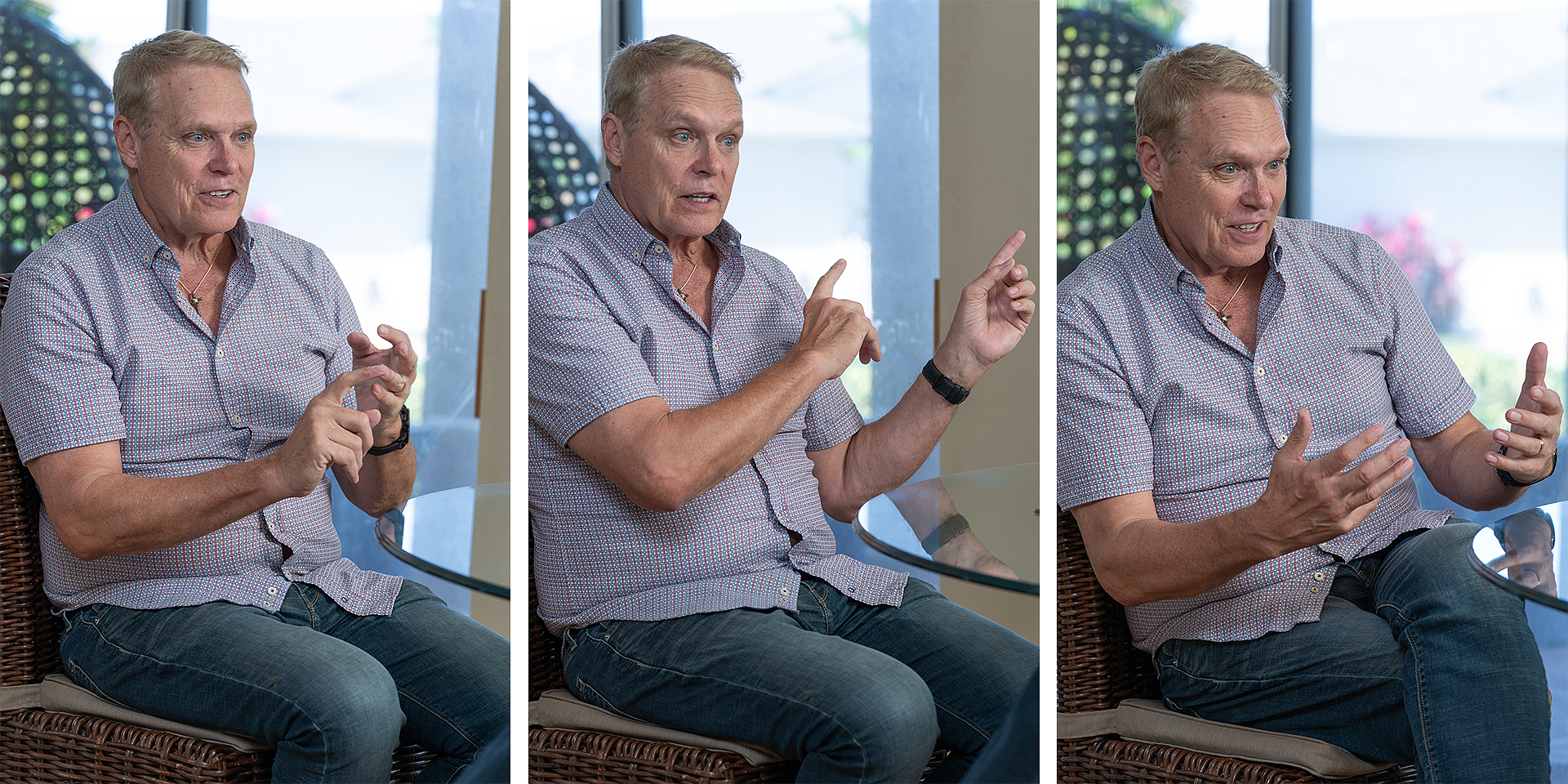

On a crisp day in mid-February, Tammy opens the door to the Sachs’ home just a few blocks from Gulf of Mexico Drive. She is Chris’s second wife, nine years younger. The native of St. Augustine greets me with cheery Southern charm. Chris approaches with a smile and an outstretched hand. He’s about 6-foot-3, with broad shoulders. His blue eyes manage to project both intensity and warmth. We sit at a table next to the kitchen. He opens a Moleskine notebook and sips coffee from a white cup.

Chris and Tammy did not choose Longboat Key at random. A couple of miles up Gulf of Mexico Drive stands The Diplomat Beach Resort, where Sachs’ father and business associate booked a block of rooms for their families during Thanksgiving and Easter breaks. The tradition started when Chris, the youngest of four, was 11. He was part of a gaggle of kids who roamed the beach and meandered up to The Colony Beach & Tennis Resort, where they’d hang out by the pool and grab a hot dog at the Monkey Bar. Sachs’ parents bought a condo nearby in 1970 and eventually became snowbirds.

Chris and Tammy did not. They live in Longboat Key year-round, although they take trips, mostly during the summer dog days.

Sachs’ father, John, was educated as a chemical engineer and became a high-ranking executive at Union Carbide and later the CEO of Great Lakes Carbon Corp. He and his wife, Mary K, raised their kids in Stamford, Connecticut, 10 miles from New Canaan. By Sachs’ account, it was an idyllic childhood. He played football, basketball and baseball, but says he didn’t excel at any of them, choosing participation over intense competitiveness. The Sachs clan went on ski outings nearly every weekend during the winter.

Sachs attended Catholic grade school and high school, then went to Fairfield University, a small Jesuit institution 20 miles from home. Devout Catholicism is a family mainstay. One of Sachs’ brothers is a Jesuit priest.

Sachs started out as a psychology major, then switched over to the business side and earned a degree in marketing. He also served as news editor of The Fairfield Mirror, the student newspaper.

“As a people person, sales had a natural gravitational pull,” Sachs says. His first job out of college was selling business office equipment for 3M. But Sachs was a magazine aficionado, and soon joined the sales staff at Life, with a client list concentrated in consumer electronics.

On his commutes to New York and back — about an hour and 10 minutes each way — he read three newspapers, played the occasional round of bridge and spent time in the bar car (on the return home, that is). “Those train rides were important,” he recalls. “You had your community buddies and your work buddies, but you had your train buddies, too. They made for some strong relationships.”

Sachs married Christina Forstl in 1986. His career success enabled her to stay at home and raise their four kids, which he’s quick to point out “is the toughest job in the world.” The couple divorced after 20 years but remained friends. Sachs stayed deeply involved in his children’s lives. “People would ask me, ‘Are you sure you’re divorced?’”

In 1992, Men’s Journal recruited Sachs to lead its ad sales team. Wenner has long been a controversial figure, but Sachs has nothing but praise for him: “He was turning 50 the year he launched the magazine, and his lifestyle was different from the Rolling Stone years. He had three children by then. Men’s Journal was about spending quality time. Time as currency. It spoke to men of a certain age who had already worked as hard as they could work. It’s like, ‘Well, what are the benefits of that?’ Nobody goes to the grave wishing they had spent more time at the office.”

After Sachs put in six years at Men’s Journal, headhunters wrangled him to help start up National Geographic Adventure, a spin-off intended as a fun alternative to the august mothership. Sachs was not involved with editorial but nevertheless helped shape the magazine. “I was able to give ideas about what kind of publication people would want to subscribe to and advertisers would want to buy space in,” he says. Sachs is particularly proud of Adventure winning a National Magazine Award for General Excellence in its second year of publication.

Sachs stayed at Adventure for about eight years — it ceased print publication in 2009 — and with a few associates formed a company focused on developing adventure TV programing. In 2012, the firm was bought out and Sachs earned his golden parachute, providing him enough of a financial windfall to retire at age 55. He keeps his days full. Sachs serves on the board of his HOA and is vice president of the Republican Club of Longboat Key.

All told, Chris Sachs’ story is a classic one — that of climbing the corporate ladder and building a comfortable, happy life for his family in suburbia, unburdened by the alienation and ennui that literature would have us believe is part of the package. He was able to retire early and devote much of his time to service and family.

Even Sachs’ divorce worked out well in the end. His first wife remarried a wonderful guy, he says, and both sides of the family have blended beautifully. “Tammy asks me, ‘How is it that your ex-wife and I are best friends?” he says with a smile.

Asked if he feels like he’s lived a charmed life, Sachs pauses. “You could say that, but I prefer to think of it as a blessed life. I’ve lived a very blessed life.”