- May 4, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

There was a time when the most famous writer who ever lived made his home in Siesta Key.

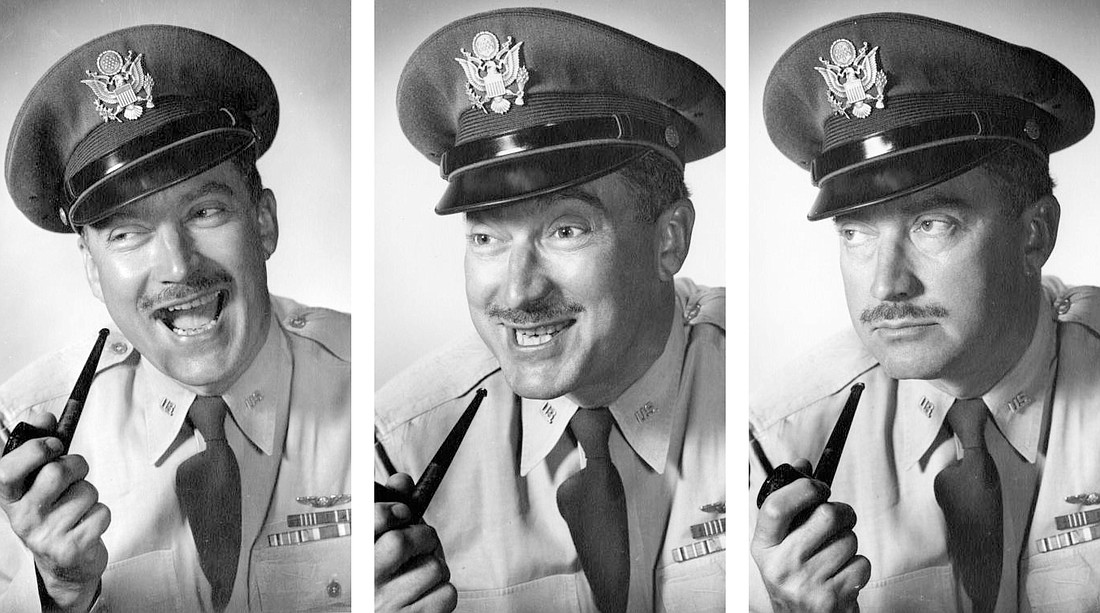

While that lofty title is based on the tall tales he told his children, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist MacKinlay Kantor was one of the most famous and bestselling authors in the country, if not the world. For a time.

This was in the middle decades of the last century, the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, back when a writer could still be a celebrity, grace magazine covers and make the society pages. This was a time when you could be a star if you knew how to tell a story.

And Kantor could tell a story. He wrote more than 40 books, published countless short stories, was a war correspondent and wrote the original screenplay for the Oscar-winning film “The Best Years of Our Lives” and the book it was based on, “Glory for Me.”

And like big stars, he drove big cars. Yellow ones — sometimes a Lincoln, an Oldsmobile or a Cadillac. He drove them all around Sarasota; a homemade cupholder kept his drink from spilling.

He spent big, drank big, and traveled big. He once took a two-month cruise so he could write a book simply because he liked to write on cruises. Ernest Hemingway came by Siesta Key for visits. Kantor discovered Burl Ives and hung out with Gregory Peck. Other stars.

But Kantor died in 1977 at Sarasota Memorial Hospital broke, broken and largely forgotten. His last words were “Horrible! Horrible!”

In Sarasota, he had been a king of writers, a founding member of the famous writers’ group, the Liar’s Club. He was also a friend and mentor of the man who one day would become the godfather of the Florida crime novel, John D. MacDonald.

Kantor had been admired, lauded, worshiped even.

His famed novel “Andersonville,” was a massive bestseller, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1956. It was based in part on his experiences during WWII. Kantor was among the first to witness the savagery of the Nazis when as a war correspondent he arrived at the Buchenwald concentration camp days after it was liberated, the bloated corpses still sitting in the sun.

In the end there wasn’t enough money to pay for Kantor’s funeral. MacDonald, a bestseller by then, helped pay some of Kantor’s serious debts. The house on Siesta Key was sold to satisfy others. The little left over allowed his wife a modest life in her final years.

The story of the self-proclaimed “most famous writer who ever lived” lacks one thing readers want — whether they admit it or not — a happy ending.

Kantor’s father deserted the family before MacKinlay was born in 1904. Kantor grew up poor in and around Webster, Iowa.

For years Kantor struggled, working as a reporter in Chicago for a time, and in Montreal, and Iowa. In Chicago he met then married Irene Layne in 1926. He eked out a living, writing at the kitchen table with diapers drying on a line behind him.

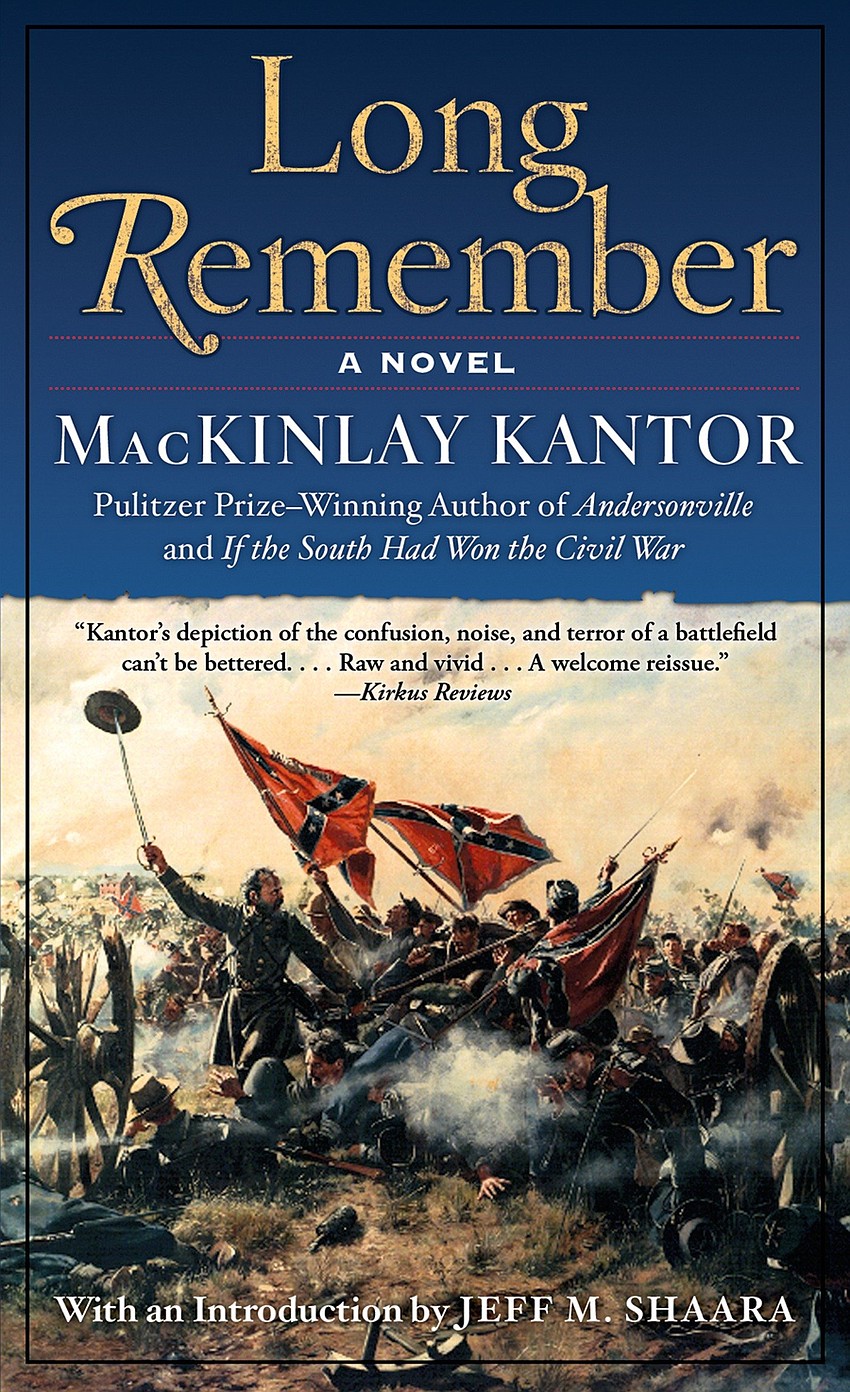

When “Long Remember,” a novel about the Civil War, was published in 1934 he found the commercial success he’d longed for.

“Certainly, from his perspective, he was suddenly rich,” said Tom Shroder, Kantor’s grandson and the author of the biography “The Most Famous Writer Who Ever Lived: A True Story of My Family.”

With finances now no longer a problem, Kantor and his wife Irene took a trip to Florida in 1936, driving around the state and eventually making their way to Sarasota and Siesta Key. Irene fell in love.

They eventually bought property on Shell Road. In 1937 they built a one-story house. The house sat on Sarasota Bay and was surrounded by what seemed like acres of wild jungle. There they would live for most of their lives and raise their son and a daughter.

There were screened patios with sliding-glass doors at either end of the house with sliding-glass doors and the lawn backed up to Shell Road and a path to the beach. Ocean breezes blew through the house, keeping it cool.

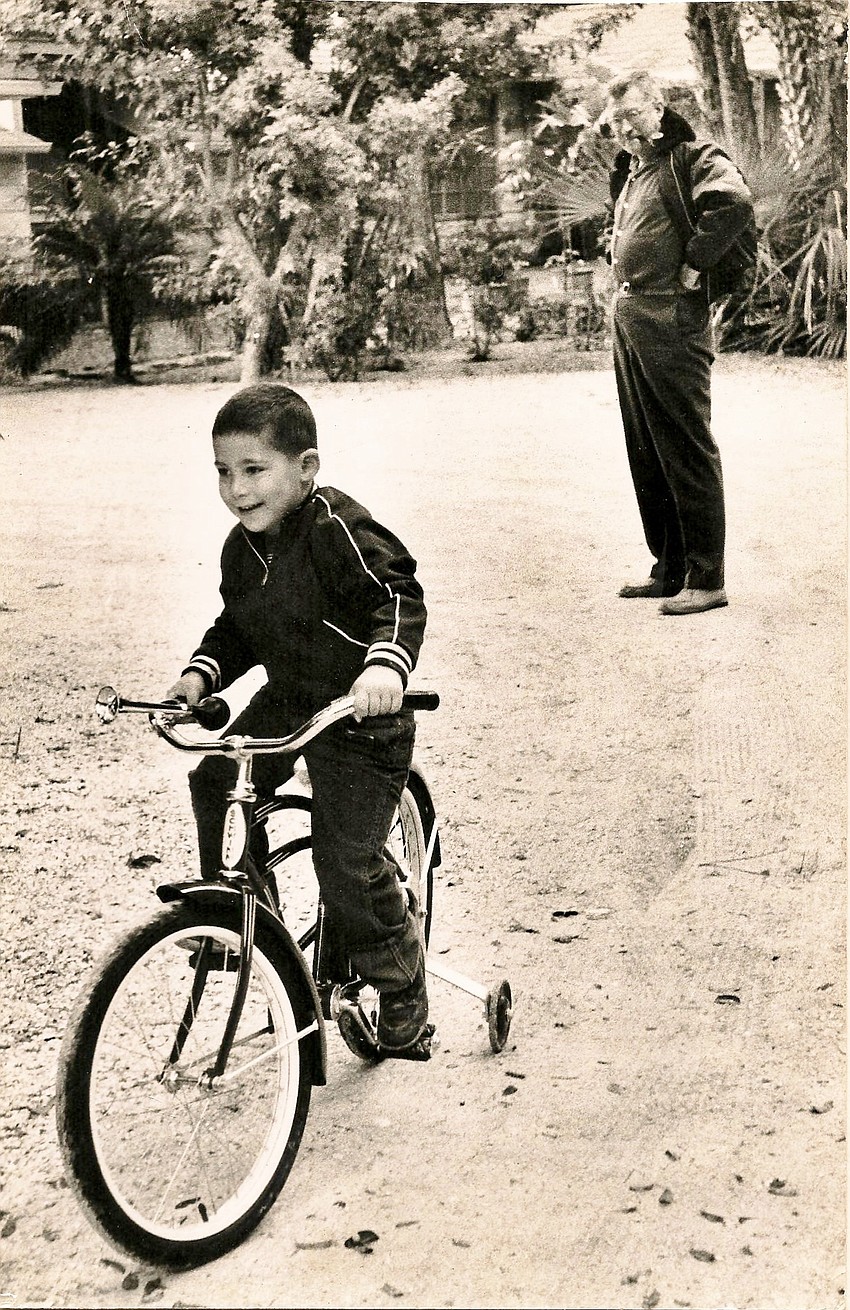

Shroder remembers big cabbage palms with “cactus like things” hanging from them in the backyard. His grandfather let Shroder shoot them with a bow and arrow. He also remembers riding a new bike, a Christmas present from Kantor, in the front.

(While he visited the house almost every year of his childhood, Shroder’s memories of it are mostly after it was renovated in the late 1950s, when “Andersonville” became a bestseller.)

Life was good in those days and Kantor was living large — touring the world, basking in his celebrity, working and spending money as quickly as he got it. He believed that he would go on writing bestsellers forever, churning them out on demand. After experiencing so much poverty in his early life, he picked up the check at restaurants and stayed in the best hotels.

Shroder, who moved to Sarasota from New York when he was 14, remembers Kantor visiting his family when they still lived in New York, his grandparents showing up in a stretch limousine.

It seemed like the dream would never end.

Kantor sustained his lifestyle for years due to the sales of his books and other writing.

And the books were good. Kantor was no hack churning out cheap bestsellers to be consumed en masse. He was a talented writer, a craftsman, who created powerful and impactful narratives because of the research and reporting he did.

A 1934 New York Times review of “Long Remember,” a story about the Battle of Gettysburg, calls it “a novel that tastes and smells of war till the reader hates the smell and taste of it.”

“Fiction naturally it is but the truth could hardly be more compelling than this story,” the review said.

Patrick Cesarini, an associate professor of literature at the University of South Alabama who specializes in American literature from the colonial period to 1900, wrote in an essay titled “Andersonville and the Literature of Violence” about Kantor’s approach and the strength of the book.

“Andersonville” is the story of a notorious Georgia prison camp told from the perspective of the Yankee prisoners, the Confederate guards and the people living nearby. While the camp is one the main characters, Cesarini wrote that the book’s strength, in part, is that it delves into the lives of the characters who lived through the war, telling their stories in painstaking detail, allowing the reader to get to know them, watching them grow and then, inevitably, watching them die “in almost every case, and die in the most degrading fashion.”

Cesarini was initially surprised that prominent scholars called the book the best novel written about the Civil War, because it is not about a particular battle.

“But, now I think I see what they meant. It is a variation on what Walt Whitman meant when he lamented repeatedly in his Civil War diary that the real war was too vast — too vastly heroic and horrible — ever to get into the books,” Cesarini wrote. “That, for me, seemed at first to be MacKinlay Kantor's achievement. To me, it felt like he did get the real war, and in some sense the whole war, into his book. And, this is partly because, as many historians agree, the Civil War was one of the first truly modern wars, and modern wars are horrible in ways that we still have trouble seeing clearly, and I believe MacKinlay Kantor saw that.”

In an email for this story, Cesarini said there was nothing to add to what he’d written. “I really do admire 'Andersonville,' though, and I wish more people would read it!”

American culture began to change in the 1960s and ’70s. Long books about war didn’t sell in the era of Vietnam. And Kantor, who had spent wildly, believing he could write bestsellers on demand, found himself out of favor with the public.

In his book, Shroder, who was born in 1954, wrote about his feelings toward his grandfather’s books at the time, saying he judged the writing then “as overly mannered, alternately tediously detailed and overwritten, and sometimes downright hokey.”

He wasn’t alone, Shroder wrote. One reviewer of the time called Kantor’s books “embarrassingly jingoistic” and another wrote “Your grandfather and grandmother would take him to their respective bosoms. Your present-day college son and daughter would find him strictly ‘Squaresville.’”

The inability to write books that sold well anymore, coupled with years of undisciplined spending meant that he accrued significant debt in the final years of his life. Kantor had to mortgage the Siesta Key house.

Kantor continued to believe in himself even as sales dried up and publishers rejected his ideas.

“He never stopped until he got really sick at the very end,” Shroder said. “And even at the end of his life, he had to end up doing a book for hire. I'm sure it was a real killer to have to do that, but he needed the money.”

That’s when MacDonald, who lived down the street in Siesta Key, stepped in to help.

In an odd twist, MacDonald may not have been in the position to help had he taken Kantor’s advice years earlier.

MacDonald, a revered writer of mystery novels who has now influenced at least three generations of Florida writers, for years was told by Kantor to forgo the genre and write something serious. Tired of the ribbing, one night in 1960 a fed-up MacDonald wrote his old friend, mentor and fellow Liar’s Club member a letter.

“It has been your habit (over the years I’ve known you) to make snide remarks about the work I do which is of importance to me,” the letter said. “They have stung. I have been unable to laugh. You speak of ‘that mystery stuff’ with slurring indifference.”

Gene Weingarten, the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and a close friend of Shroder, wrote about the letter in his book “One Day: The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 Hours in America.” (The book focuses on Dec. 28, 1986, the day MacDonald died.)

Weingarten wrote, “MacDonald did not yet know exactly who he was as a writer, nor precisely where he was going, but he knew he was not the unambitious hack in training that Kantor apparently saw.”

Seventeen years after the letter, “that mystery stuff” had made MacDonald millions, Shroder said, and that money helped bail Kantor out when, in his old age, he was most desperate.

This was early 1977, and after years of heavy drinking and not taking care of himself, Kantor, Irene and their two children were told he had 10 days, possibly two weeks, to live.

There were many debts and the family feared Kantor and Irene would wind up losing their home of 40 years. That’s when MacDonald stepped in and helped out, saving them.

Kantor held on, not for days but for months. When the end came, it came fast.

In the latter half of 1977, as Kantor lay in the house wasting away suffering from heart problems, Irene fell on the beach and broke her wrist “and the last strand of her resilience broke with it,” Shroder wrote.

“She went to the hospital for surgery on her shattered bone and came out with a shattered mind.”

That same week, the couple’s children sent Kantor’s “spent shell of a body” into the hospital.

Shroder was working as a reporter in Fort Myers at the time. He drove to Sarasota to see his grandfather. He writes in the book about what he saw: “His body had shrunken horribly, his skin sallow, he was breathing ragged. Tethered to a web of tubes, he looked like one of the inmates of the Andersonville prison he’d written about — tortured, starved, barely alive.”

MacKinlay, who proclaimed himself the most famous writer who ever lived, the Iowa boy who grew up to live, laugh and drink big, the man who graced magazines and took over the rooms he walked into, died Oct. 11, 1977, in Sarasota. He was 73. His grandson was at his side. Irene, who outlived Kantor by five years, sold the Siesta Key house after he died and was able to survive on what money was left from the sale.

Kantor’s obituary appeared on Page D20 of the New York Times the next day. Without a photo. Below his obituary, was one for Isidore Godfrey, the musical director of the D’Oyly Carte orchestra. And next to it, was one for Mason Welch Gross, the former president of Rutgers University.

Kantor’s memory lives on in some small ways, though.

“Andersonville” still sells well enough to fund a night out on the town for his family a couple of times a year. And in 2018, writer Griffin Dunne, the son of Dominick Dunne and nephew of Joan Didion, told the Times that once, on a visit to Howard Kaminsky, the legendary Random House publisher who died in 2017, Kaminsky handed him a copy of the book.

“It took him about 45 seconds to find it,” Dunne told the newspaper. “He pulled it off the shelf and said, ‘I know you’re going to love this one.’”

Despite the difficulties of his final years, Kantor knew that money, accolades and status are fleeting, that leaving behind something that lasts and living a good life, a big life, are what counts.

“What he said was, ‘Would you rather have a whole pile of money in the bank or all these incredible experiences that I've had?’” Shroder said. “That always made me feel good. He had the life he wanted to have.”