- April 18, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

The Unitarian Universalist Church off Fruitville Road is a long way from Brooklyn: 1,190.7 miles to be exact. Inside, it’s pretty clear you’re not in Brooklyn. Especially in one bright, Sunday School classroom full of happy posters and toys. But it’s Brooklyn in the minds of the four actors who have gathered there to rehearse Arthur Miller’s “A View from the Bridge.”

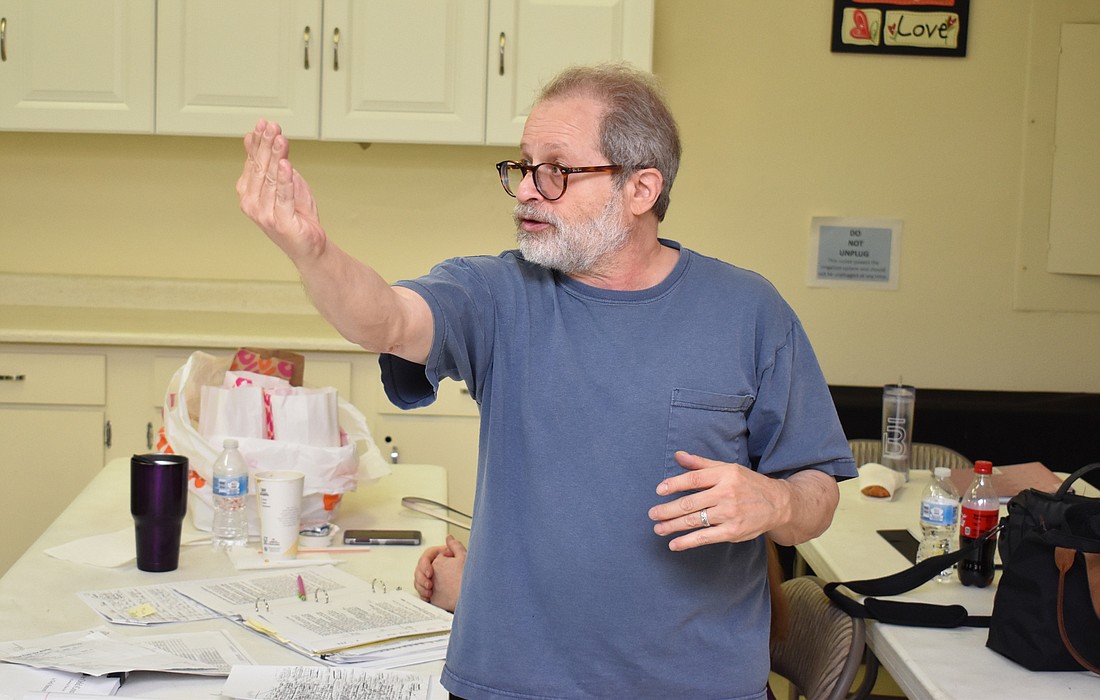

As I enter, the actors are gearing up for a read-through. They’re sitting at a round table like King Arthur’s knights. Director Elliott Raines sits at four o’clock, holding his copy of the script. He’s packed the margins with dense, handwritten notes.

I’m not surprised. He had told me about it in a long conversation a few days before. The chat was a bit one-sided. “How do you take a play from the page to the stage?” was my question. The rest of the talk was Raines’ answer.

Although he ends up as a director, Raines starts out as a reader. Before casting and staging a play, he devours the script. That means an intense, close, X-ray reading of the playwright’s words. Raines gets between the lines — and tries to get into the playwright’s head.

This deep dive into the text usually takes eight weeks. Raines got through “A View from the Bridge” in six. He had a late start, thanks to quadruple heart bypass surgery. And got to work as soon as he recovered.

Raines did an initial reading. On the second pass, he started breaking the script down. Line-by-line and word-by-word, he dug into the play’s fundamental structure. How does he define that?

“OK … What’s the basic element of a play? People think it’s the scene, but that’s more like a molecule. To me, the beat is the atom of a play. I define that as a self-contained action with its own mini-climax.”

After taking the play apart, Raines puts it back together. He shifts to a musical metaphor to explain this process.

“Each beat is like a musical note,” he says. “I have to hear the music. I have to find the rhythm that ties the beats together into a whole.”

Six weeks later, Raines knew the score. And filled Miller’s script with his notes. Basically, Raines did his homework. During the rehearsals, he lets the actors copy it.

That’s what’s about to happen tonight — and the timing is perfect.

By shear dumb luck, I walked in on a pivotal scene. It comes late in the second act, right before the tragic climax. And sets the tragedy in motion …

Brooklyn, 1955. The action unfolds in Red Hook, a poor, Italian-American neighborhood. Eddie thinks an illegal Italian immigrant named Rudolpho is marrying his cousin Catherine as an easy shortcut to American citizenship. Eddie rats him out to immigration services and now the whole family’s going to be deported. Marco, Rudolpho’s brother, wants to kill Eddie. Alfieri, a sympathetic lawyer, tries to talk him out of it. Marco pretends to be persuaded. But he still has murder on his mind.

Raines starts with a scene analysis. (Not my simplified synopsis. The actors already know that.) The director digs into the nitty-gritty of the characters’ motivations, setups, payoffs, the builds, emotional truths, subtexts — you name it. But it’s a Socratic dialogue, not a lecture.

The actors all hold their script copies. Raines smiles and asks the first question. He directs it at Lauren Ward, who’s playing Catherine.

“Page 56 … when immigration knocks on the door. What’s going through Catherine’s mind?”

“Catherine just realized that Eddie’s the reason immigration showed up,” she says. “He’s the only possible informer.”

“Exactly. But I think that’s still too general. We need to see a clear, specific moment of realization.”

“Like a reaction when she gets it?”

“Yeah. Disgust, hatred, revulsion, whatever.”

Rick Robertson speaks. Marco is his character.

“And I see her react. And I respond in my next line?”

“You got it.”

After the Socratic Q&A, the table reading officially starts. It sounds like a radio drama — a good one. And maybe it’s my imagination, but the actors don’t seem to be looking each other in the eye.

I ask about it during the break.

“No, it’s not your imagination,” Raines says. “I don’t let the actors look at each other during early rehearsals. I want their faces in the script.”

Why?

“It’s a way to find the rhythm. Actors break the flow if they have to keep reacting to each other. You look up; you look back; you look up. When you can’t see the other actors, you’re forced to listen. There’s no other choice. You can’t get clues from facial expressions. You can only react to what they’re saying.”

After the break, the actors get on their feet. Raines blocks out the parameters of the scene with Sunday school paraphernalia. Bright plastic chairs stand in for a dingy Brooklyn apartment.

Before they start the scene, two actors ask about stage directions.

“Ignore them,” Raines says. “Always ignore the stage directions.”

What about authorial intent? I don’t ask that question. But he must have seen it in my eyes.

“Stage directions are usually not from the author. They’re from the stage manager in the first run.”

Good enough.

The actors do the scene. Raines offers suggestions. The actors take them in stride — and make a few suggestions of their own. The director takes it in stride. He clearly knows the difference between director and dictator.

“My notes aren’t written in stone,” he says. “If an actor has a better idea, I want to hear it. Even if it’s lousy, I still want to hear it. Maybe it won’t work. But you have to go through all the bad ideas to get to the brilliant one. Actors should feel free to take that risk for their characters. I’m just the director. In the end, each actor has to own their part.”

Before hitting the road, there’s one last question.

Where does this scene take us? Did Marco fool his friends? Or do they know in their hearts that he’s planning a murder?

“Great question,” says Raines. “The answer is: We don’t know yet. We’re still working through that. You’ll have to see the play to find out.”