- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Whether they saw combat or not, local veterans carry memories from their time in the service. We asked three veterans about their most memorable times in the military.

Three local veterans, one from the Army, one from the Air Force and one from the Navy share their most prominent memories.

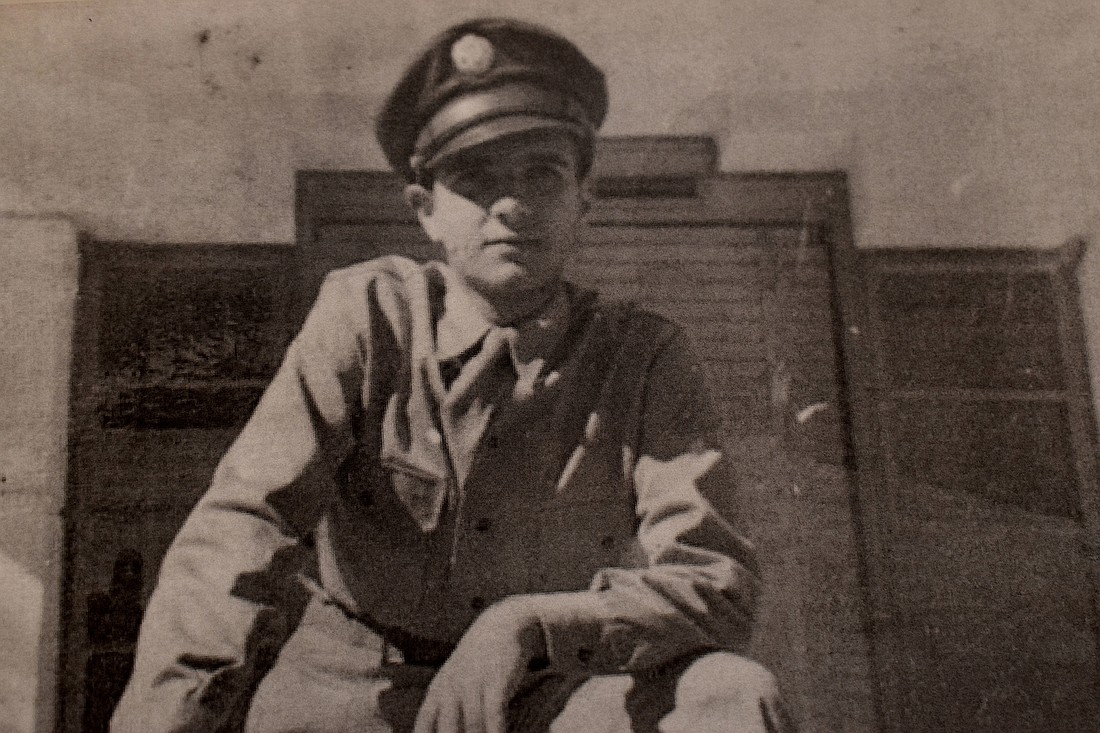

Mort Mandle

Mandle enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps, the predecessor of the U.S. Air Force, in 1942 at the age of 18. Mandle enlisted with college friends out of question of loyalty to the United States. Mandle said if you were breathing you were needed.

“Well, at that time, Hitler was a real threat to the United States,” he said. “I was in college. I was in my second year of college, and five of us decided that our country was in jeopardy. Also, I am Jewish, and we had heard about what was going on with the Holocaust, so the five of us decided to enlist, not even telling our parents, and I enlisted and then served for four years.”

He was sent to learn radio and radar. He wanted to fly.

Right before he was to deploy overseas, he was sent instead to Salt Lake City to teach graduating crews radio and radar. After time in Nebraska and a few other places, he was stationed in Kingston, Jamaica. He taught crews how to fly B-29s, the planes that dropped the atomic bombs in Japan.

Mandle and the other teachers had no idea the mission for which they were training their crews. Though, looking back, Mandle said the B-29 bombers they were flying had been stripped of defensive machine guns.

“And we thought that was kind of strange,” he said. “But the reason for it was they would carry less fuel, and they would be supported by fighter planes.”

Despite being able to fly when teaching crews, Mandle said he wished he could have done more than teach.

“I wanted to actually fight for my country, and they wouldn’t let me do that,” he said.

He hopes the military kept him as a teacher because he was good at it. As for the friends he enlisted with, one of them died in combat and the others were spread out around the country.

One of them, though, became his student.

“Out of 4 million men, I met up with my closest friend and was teaching him radio,” Mandle said. “He was a bombardier there [Salt Lake City], which was a nice experience.”

James Ahstrom

Two weeks after his high school graduation, Dr. James Ahstrom enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

He elected a pre-med track, and the Navy sent him to University of Richmond. He completed six semesters in two calendar years, becoming a corpsman at the naval hospital in Portsmouth, Va. He started medical school in 1945 at Northwestern University. In December 1945, he was put on inactive duty, but in November 1950 he was activated and loaned to the Army.

Following World War II, many military doctors resigned and went on inactive duty. So, the Navy sent 500 doctors to Fort Sam Houston in Texas.

“Basic training was supposed to be about six weeks, but it was only two weeks for us because they were in a hurry,” Ahstrom said. “Fifty of us went to Korea and took a boat from San Francisco, and halfway over across the Pacific, the Chinese came into the war.”

Eventually, Ahstrom ended up in Taegu, now Daegu, in South Korea at a Presbyterian college turned hospital.

“This was the fourth field hospital in Taegu,” he said. “The field hospital is supposed to have 400 beds. By the time we finished there, we had 1,000 beds.”

Ahstrom was one of three orthopedic doctors on site.

“When they were really active, and the Chinese were active a lot, there’d be lots of casualties, and they sent the men by the trainload, and we’d have to treat them,” he said.

At times, Ahstrom treated soldiers with a half-dozen wounds at once. Often, one doctor would be in charge of deciding who needed to be treated immediately and who could wait.

In July 1951, Ahstrom returned to the U.S. and was stationed at the naval hospital in Oakland, Calif. Some of his time there counted toward the residency he had started before being recalled to active duty. In 1952, he was discharged.

Jacob Pollack

Jacob Pollack was in the Army for 11 months and 18 days.

He received an induction notice in March 1944, but was a quarter credit away from graduating high school. His principal wrote the Army asking for an extension. The Army obliged and Pollack took a typing course to satisfy his graduation requirements. That typing course would change the course of his military service.

While waiting at the port to ship out in June 1944, a sergeant asked who knew how to type. Pollack was the only one who raised his hand. So, he became the sergeant’s clerk typist. In early 1945, while recovering from an infection in Italy, another sergeant looked at his service record and noticed his clerk-typist experience and put him to work.

In April 1945, two days after President Franklin Roosevelt died, he was assigned to the 10th Mountain Division, which was operating in the Po Valley, in the north of Italy.

Once in Po Valley, Pollack’s squad had to set up guard duty. Pollack was assigned the first shift of night watch. He was given a password — bronze star — and was told that if someone approaches he needs to say “bronze.” If the person who approached doesn’t say “star,” Pollack was instructed to shoot them.

“By this time, things were happening fast in Po Valley, and who was coming down the road on bikes but Italian partisans,” Pollack said. “I said ‘halt’ but they went by on bikes, and they kept saying ‘partizani, partizani.”

When the war in Italy ended, Pollack went to Fort Sheridan in Illinois and once again became a clerk typist.