- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

“The law is a weapon.” Thurgood Marshall was fond of saying that. The current production of George Stevens Jr.’s “Thurgood” at Florida Studio Theatre shows how he put this principle into action over a lifetime spent as a warrior of the law.

Thurgood Marshall was the first African-American to serve on the Supreme Court. Consideration of this honor comes late in this one-man play — which comes in the form of Marshall’s 1991 address to students of Howard University Law School. (The FST audience functions as a stand-in for law students.) “Paper Chase” it’s not. Marshall spins the tumblers of your mind, all right. But legal theory isn’t his focus. This warrior of the law is more obsessed with legal strategy. It’s like listening to General Patton reminisce about how he fought and won his battles. Marshall’s battles are against the edifice of segregation in the United States.

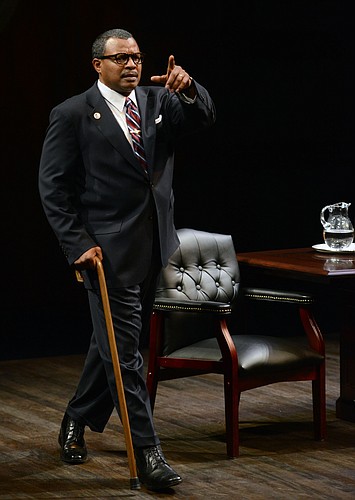

The aged Marshall (Montae Russell) limps with a cane. But he sets it aside when reliving his youth. He takes us back to the early days of segregated public schools in Baltimore. His school had front-row seats on a police station next door, where white officers would routinely beat and abuse black prisoners.

Marshall’s humiliations begin early. First, racial slurs. Then denial to the University of Maryland Law School on the basis of his skin pigmentation. “Am I going to go through life being humiliated because of the color of my skin?” He asks himself this question. And the answer is no.

Marshall studies at Howard University, graduates with honors, becomes chief counsel for the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and gets into the fight. He knows his enemy from the start: Plessy vs. Ferguson — the 1898 Supreme Court ruling that established the “separate but equal” doctrine. Marshall is a man of principle. But he wants to fight battles he can win.

He doesn’t go after the principle itself, at first. In a kind of Aikido move, he uses the principle against itself. If “separate but equal” is the law of the land, each state is compelled to create “equal” facilities for African-Americans, right? On that basis, Marshall wins equal pay for black school teachers in Maryland, his mother included. He compels the University of Maryland to accept black law students, because it’s either that, or create a truly equal black law school.

But such triumphs are only skirmishes. Ultimately, the real fight is at the Supreme Court. Brown vs. Board of Education is the battle to win the war.

Marshall argues for the plaintiffs. His opponent: the smarmy, slick-talking John W. Davis—the defense attorney arguing for the separate but equal principle. Davis makes a good case. But Marshall wins the case. All nine of the Supreme Court justices agree that separate can’t be equal. The principle behind segregation is just plain wrong. In 1954, the highest court in the land strikes Plessy vs. Ferguson down. It’s largely thanks to Marshall’s relentless attack.

The play leads us up to this victory — and the triumphs and tragedies that follow. Marshall risks lynching to work in the South; he stands up to Gen.l Douglas MacArthur’s racism — and stands for African American soldiers unjustly court martialed for cowardice. He loses his first wife to cancer. His second wife gives him two sons.

The playwright distilled the 90-minute play from a screenplay for a three-hour movie — which, in turn was distilled from Marshall’s journals, letters, speeches and interviews and essays. It’s a portrait of a great man — and a great (and hilarious) storyteller. But he’s no wind-up saint. Marshall had a healthy ego — and a relentless competitive drive. Revenge, cold or hot, was a dish he occasionally savored. He liked to drink and loved the company of women. (Marshall assured his second wife he wouldn’t let his children do anything he wouldn’t do. She replied: "Great. That means you’ll let them do anything.")

Marshall’s unvarnished humanity makes his victories all the more satisfying. Russell conveys Marshall’s essence in a warm, charismatic performance that had the opening-night audience in the palm of his hand. Based on that performance, this was a man who loved life, loves to fight — and, above all, loves to win.

This one-man play comes in the form of a lecture. Director Kate Alexander makes you feel like you’re on a trip through time. She creates a tone that’s passionate but never strident — and draws you into an encounter with Marshall’s mercurial, loving-but-combative mind. This isn’t just a history lesson. Alexander's deft approach makes you want to get to know the man.

The FST design team creates Marshall’s environment and flow of experience, conveyed as a low-rent Howard University lecture hall, with projected images of Marshall’s life on a bleached-out American flag in the background. Kudos to costume designer Susan Angermann, lighting designer Dave Upton, scenic designer Bruce Price, stage manager Garry Allan Breul and production stage manager Kelli Karen for creating the world of this warrior.

And what a warrior he was.

Largely thanks to Marshall’s intellect and tenacity, the phrase “Equal justice under law” became more than a carved slogan on the pediment of the Supreme Court Building. The end of segregation seems a historical inevitability now, but it was truly a historic victory. Watching this powerful one-man play makes it clear that Marshall was one of the key warriors in that struggle.

As it turns out, our original quote was incomplete.

“The law is a weapon, if you know how to use it,” is the full quote.

Marshall knew.

IF YOU GO

“Thurgood” runs through Feb. 22, at Florida Studio Theatre’s Keating Theatre, 1247 First St., Sarasota. Call 366-9000 or visit floridastudiotheatre.org for more information.