- April 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Sunday began just like any other day for Robert O’Neill on his U.S. Naval base. Up at the crack of dawn, he put on his crisp uniform, made his bed and walked with a buddy toward the mess hall.

But that Sunday was Dec. 7, 1941 — and would become unlike any other day at Pearl Harbor.

“We were on our way to get breakfast (when the Japanese attacked),” O’Neill said. “My first job was picking up bodies … a 17-year-old picking up bodies.”

O’Neill is just one example of the sentiment that war makes kids grow up quickly.

“At 7:45 a.m. Dec. 7, there were 3,000 boys on the base,” he said. “By 3 o’clock, there were 3,000 men. Childhood was all forgotten.”

To commemorate the country’s 91st Veterans Day, The Sarasota Observer sat down with O’Neill and two other Sarasota veterans to talk about life in the military, life as a veteran and life and death in war.

Sgt. Andy Hooker was an Army helicopter door gunner in Vietnam, and Marine Maj. Jamie Purmort served in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, earning a Bronze Star for his heroics.

All three men have times when they joke about the dangers they survived and times when they reflect on them.

Purmort jokes that he was awarded the Bronze Star “for not getting killed.”

In actuality, the medal was earned after Purmort helped defend a compound in Al Kut, Iraq, that was surrounded by about 600 enemy soldiers.

The 6-foot-5-inch, soft-spoken man was awake for about 96 hours straight as his team battled non-stop fire. Purmort was directing U.S. air support, conducting strikes on the enemy.

Hooker says the life expectancy of a door gunner in Vietnam was about three months — he survived four years of combat.

“We saw action every day,” said Hooker. “We operated 24/7.”

At a reunion of veterans in his unit, Hooker ran into the man who trained him to be a door gunner.

With a surprised look on his face, the man said to Hooker, “I don’t know how you made it.”

Call to action

O’Neill is a career military man, who not only served in World War II, but also the Korean and Vietnam wars, spending his time primarily on submarines in the Pacific, where they “served the best food in the military.”

One of the duties of the men on the submarine was to rescue downed American fighter pilots.

“We’d pick them up out of the water,” said O’Neill.

One particular pilot was so grateful that he gave O’Neill his Army Air Force scarf. The two men became friends and kept in touch over the years. That pilot died just a couple of years ago.

The scarf has been a cherished memento for O’Neill, who carries it in his briefcase to many of the veterans events he attends each year.

Two other mementos keep the scarf company in that briefcase — two Japanese flags.

One flag, collected from a P.O.W. camp, is so delicate these days that he can’t remove it from the envelope in which he keeps it without it falling apart.

The other flag was found on an island off the coast of Japan. It’s covered with Japanese writing.

Mementos serve several purposes for servicemen. Some use them to get through the rigors of combat, reminding them of loved ones back home. And others bring mementos home with them from abroad to remember their service and their buddies.

Hooker’s memento is his Falcons badge, signifying his service aboard armed helicopters.

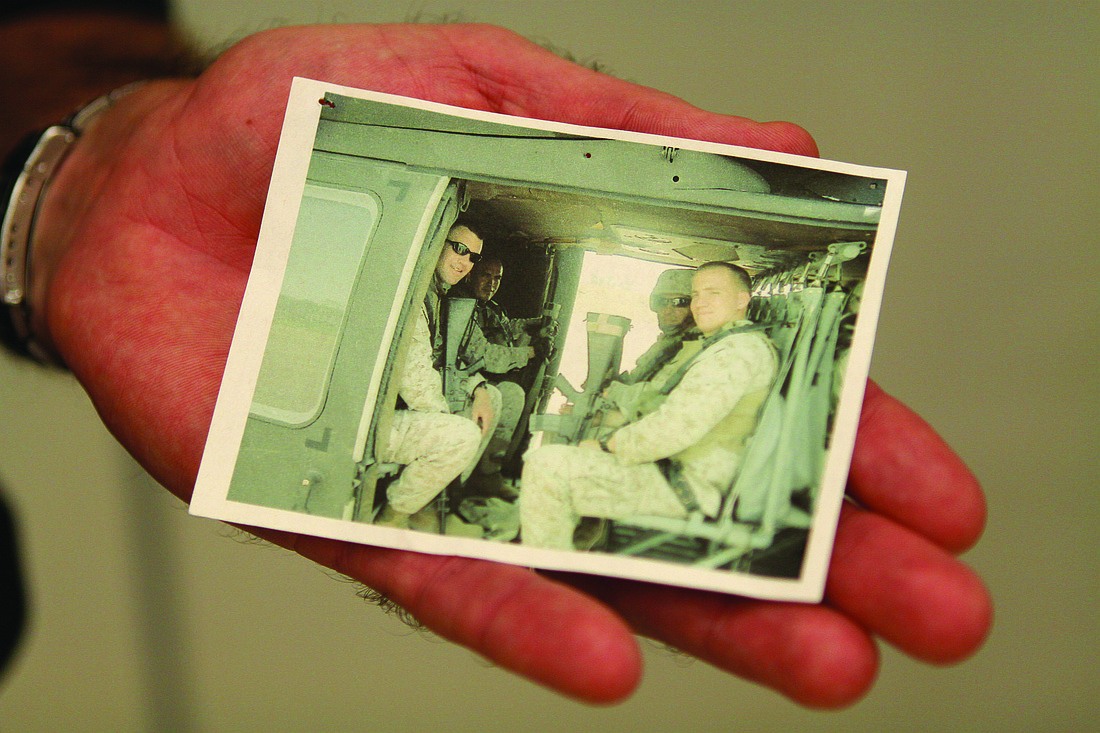

A photo aboard a helicopter is one of the items Purmort holds onto closely. It shows he and three fellow Marines just before they lifted off and left Iraq for home.

The decision to join

Enlisting was a foregone conclusion for O’Neill — his father was a Navy recruiter.

“I was born into the Navy,” he says with pride.

For the other two veterans, the decision to serve came about in different ways.

“A buddy in high school and I decided to enlist together, instead of being drafted,” Hooker said. “We were 18 years old.”

Purmort signed up with the Marines in 1991 — right after the first Gulf War.

“I wasn’t ready for a day job, and I wanted to see the world,” he says, and then adds with a smile, “I thought the Marines could straighten me out. I didn’t have a stellar college career.”

Although each man underwent extensive training before heading off to war, they say no amount of practice could have prepared the servicemen for their first day of actual combat.

“The first time I saw a tracer coming at me, I thought, ‘Hmm, that’s interesting,’” said Purmort. “You see it before you hear it.”

Said Hooker: “You’re never prepared for the real deal. My first day of action, I got sick. You don’t want to be sick on a helicopter.”

The helicopters in Vietnam were susceptible to heavy enemy fire, because they were so visible and flew so low to the ground. The choppers didn’t have doors, because they took a lot of hits. Less metal meant less shrapnel.

“We trained very hard under a lot of stress,” said Purmort. “Once the fighting began, the training kicked in. I spent 11 years getting ready for the ‘Super

Bowl.’”

After days, weeks and years of combat, Hooker began getting used to the demanding routine. One of the most important survival tools, he said, was learning how to shut down his emotions.

“You have to get into survival mode,” Hooker said. “When people say they’re not scared, they’re ‘BS’ing. You’re scared every day.”

And all three men agree that it takes a while for servicemen to turn those emotions back on when they return home, although Hooker believes there are varying degrees to that.

“It depends on the time (in which) you served,” he said. “Today, you see the sentiment of the country (supporting veterans). We can now separate politics from the war.”

It wasn’t the same during the Vietnam War.

“I remember coming through San Francisco,” said Hooker. “I had my uniform on and was proud of it. (But) protesters were spitting on me.”

Some veterans began disguising themselves.

“We’d grow our hair longer when we knew we’d be going home soon to slip through an airport undetected,” he said.

“Korea and Vietnam didn’t have the patriotism of World War I and World War II,” said O’Neill, who believes that many of today’s Americans have lost much of their patriotism. “People forget about veterans,” he said. “We’re just another person walking down the street. That’s why we have Veterans Day.”

O’Neill fears that in 20 or 25 years that many will forget the significance of 9/11.

Discussing his experience in the war doesn’t always have the best effect on Hooker, but that doesn’t mean he regrets doing interviews.

He remembered after doing a magazine interview several years ago, a fellow Vietnam veteran, whom he didn’t know, approached him. The veteran told Hooker that he was suffering from the same effects.

“He said, ‘I’ve got that and that and that. I thought I was going crazy,’” recalled Hooker. “If I have one brother that comes out, I think it’s really important (to discuss the war.) We saved one guy’s life.”

Few regrets

None of the men talk about regrets — they don’t appear to have any. Each one recognizes that they had a job to do.

“Being in the military added a special skill set that only other military can understand,” Hooker said.

After Purmort enlisted and signed a six-year infantry contract, he was able to say he served in the military.

“But when I went to Iraq and back, I felt more complete in what I’ve done,” he said. “I finally got to use what I had been training for all those years.”

For O’Neill, being known as a veteran simply means “satisfaction that you’ve done your duty, your part.”

But he also comes the closest to expressing some regret at the loss of a little bit of his youth.

“My whole childhood was the Navy,” he said. “I didn’t have school outings or prom like other kids. I finished high school and college in the Navy.”

War makes kids grow up quickly.

BOX

Service Stats

Robert O’Neill

Age: 86

Hometown: Newport, R.I.

Military Branch: Navy

Rank: Captain

Wars: World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War

Career: Military

Special war mementos: Two Japanese flags: one from a prison camp and one from an island off the coast of Japan.

Andy Hooker

Age: 61

Hometown: Brooklyn, N.Y.

Military Branch: Army

Rank: Sergeant E5

War: Vietnam War

Career: Live entertainment producer for bands such as Aerosmith and Boston

Special war memento: Falcons Armed Helicopter badge

Jamie Purmort

Age: 40

Hometown: Sarasota

Military Branch: Marines

Rank: Major

Wars: Iraq and Afghanistan wars

Career: Family insurance business

Special war memento: A photo of him and fellow Marines on a helicopter, lifting off on his last day in Iraq.

Contact Robin Roy at [email protected].